Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a complex, age-related neurological disorder in the central nervous system (CNS), characterized by progressive memory loss, cognitive deficits and inability to perform activities of daily living that involves the progressive dysregulation of multiple biological pathways at multiple molecular, genetic, epigenetic, neurophysiological, and cognitive levels [1, 2]. As yet there is no consensus regarding the presence of altered awareness of memory dysfunction in the preclinical and prodromal stages of the disease. Although AD is the most common senile dementia, it is often a dilemma to differentially diagnose the insidious and fatal disease from other equally heterogeneous neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, frontal temporal dementia, vascular dementia, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome, and Huntington’s disease. Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in AD are principally composed of the hyperphosphorylated and aggregated microtubule-associated protein tau, which is one of the major AD hallmarks. In clinical practice, doctors often base diagnosis of AD on clinical examinations, brain imaging and neuropsychological tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Also cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biochemical assays of the hyperphosphorylated tau protein and the 42-amino-acid Aβ peptide level can support the diagnosis. For diagnosing the disease in preclinical and prodromal stages and developing effective treatments, it is necessary to look for new biomedical approaches, concepts, and molecular targets. It is very useful to evaluate the role of miRNAs in AD to find miRNA-based therapeutic drugs.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a principal class of small RNA regulators binding the 3’ UTRs of target mRNA and negatively post-transcriptionally regulating the expression of mRNA [3] and play key roles in multiple biological processes such as development, proliferation, metabolism, neural plasticity, inflammation, and apoptosis. Since the first reports of miRNA dysregulation in AD, it has been almost 10 years. There are three forms of altered miRNA abundance and speciation [4, 5]: 1) in brain tissues targeted by the AD process after post-mortem examination; 2) in blood serum, and 3) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Since then some overviews have assessed up- or down-regulated miRNAs in brain tissues, blood and CSF in many thousands of AD patients, but there is still no general consensus [6–8]. We must first be certain that miRNAs are really up- or down-regulated in AD before using miRNAs as therapeutic methods. In human diseases there are three kinds of mature miRNA classes: up-regulated miRNAs, down-regulated miRNAs and “de novo” miRNAs whose new expression correlates with the “onset” or “emerging presence” of the disease state [6, 7]. But no “de novo” miRNA has been reported in AD with the initiation or onset of the disease. Recently, some studies have demonstrated that in the early stages of AD there were dysregulated miRNAs and these molecules targeted multiple genes to alter key signaling pathways in the disease, which may ultimately modulate cell death mechanisms.

AD is essentially human-specific, so the evaluation of human material must be included in research of miRNA-AD. Most research has evaluated human brain miRNAs involving gene expression profiling and assessed the levels of multiple miRNAs across different parts of brain samples [9–12]. But some tissue sampling protocols did not segregate white matter from gray matter, which increased variability. This caused different cell populations and little agreement between the differentially expressed gene lists in different protocols. Despite there being more and more evidence of miRNAs for AD pathology, dysregulation of miRNAs is not totally in accordance in peripheral blood levels and brain levels, especially in the same individuals, but studies often suffered from small sample size, heterogeneous designs, and conflicting outcomes. Because of the unclear pathogenesis of AD and a lack of sensitive biomarkers, the AD diagnosis still depends on progressive occurrence of the disease. In this study, we want to evaluate the dysregulation of microRNAs related to AD to reveal the underlying complex mechanisms.

Material and methods

We aimed at defined objectives to collect all related miRNA, through extracting and analyzing data based on search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria in our study protocol. We completed the present study in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews statement [13].

Search strategy

We used controlled vocabulary and text words to search using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, PubMed, Google Scholar, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), ACP Journal Club, Database of Abstracts of Review of Effectiveness (DARE) and Scopus and Web of Science, from January 1st 2007 to June 1st, 2017. Except MEDLINE, which uses the single term MicroRNAs, others use the terms MicroRNA, mir, mirna*, microrna* for individual miRNAs. The same approach for searching the databases of AD was as follows: AD is used by MEDLINE, but others use Alzheimer’s disease, brain, cortex, cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood. We used EndNote (EndNote X7, Bld 7072, Thomson Research Soft, Stamford) to help us download all of the databases and remove duplicates. No language restrictions were applied for searching.

Selection criteria

No linguistic restrictions to avoid language bias resulted in outcomes limitations. We collected all related articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two investigators respectively reviewed the collected titles and abstracts and separately continued to evaluate the full text of potentially eligible articles. Then two investigators put their results together to resolve disagreement about eligibility. In the next step, our co-authors further assessed the risk of trial bias and finally reached a consensus on each criterion (eligible case-control studies for the present study included those which investigated miRNAs’ differential expression in brain, CSF or heparin-anticoagulated peripheral blood of AD patients and/or age- and gender-matched normal controls as inclusion criteria and case reports, conference presentations, editorials, and expert opinions as exclusion criteria). The miRNAs were identified through microarray analysis.

Data extraction

We extracted data from the included studies and listed them using the standardized datasheet. We respectively recorded expression profiles of miRNAs in brain, CSF or heparin-anticoagulated peripheral blood of AD patients and/or age- and gender-matched normal controls. In the datasheet, we listed the related miRNAs, upregulation vs. downregulation expression, the experimental models, and samples used. We also collected the experimentally verified miRNAs involving AD and listed them including miRNAs, their targets, functions, and sample used.

Applied bioinformatic analysis of miRNAs linked to AD

Through Venny diagrams (Venny; http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/), the Functional Enrichment analysis tool (FunRich; http://www.funrich.org/) and hierarchical clustering (GENE-E; https://software.broadinstitute.org/GENE-E/), we assessed common miRNAs dysregulated in the AD in different samples such as in brain, CSF or heparin-anticoagulated peripheral blood of AD patients and/or age- and gender-matched normal controls. Then we respectively analyzed common sets of AD-related miRNAs in brain, CSF or heparin-anticoagulated peripheral blood and investigated the relatedness of molecular findings on miRNAs in different studies using Heatmap analysis. We generated a matrix from multiple studies and common miRNAs for multiple comparisons, which was assigned a value of 1 if the miRNA was detected, while a value of 0 was assigned if miRNAs were not reported. Then through TargetScan (TargetScan Human Prediction of microRNA targets; http://www.targetscan.org/vert_71/) we accessed putative targets of different sets of miRNAs and through DAVID (The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery; https://david.ncifcrf.gov/), the Functional Enrichment analysis tool (FunRich; http://www.funrich.org/), and String (http://string-db.org/) we investigated the relatedness of these gene targets in cellular networks by gene ontology analysis.

Results

Study characteristics

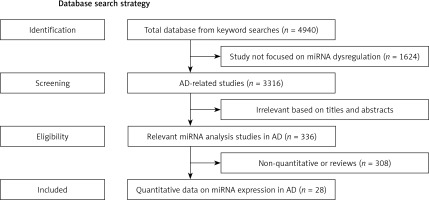

After repeated screening with inclusion and exclusion criteria we obtained the related studies of miRNA-AD association (Figure 1). The first screening obtained 3316 references that related to miRNA dysregulation. The second removed 2980 references based on titles and abstracts which did not mention actual concrete data (Figure 1). Because they lacked controls or assessment of miRNA dysregulation, 308 candidate studies were omitted (Figure 1). Finally, we obtained 28 suitable studies to perform statistics of the relationship between miRNAs and AD (Tables I and II).

Figure 1

Flow diagram shows the current system of review, identification, screening, inclusion and exclusion

Table I

Experimentally verified miRNAs involving AD

[i] ADAM10 – adisinteg- rinandmetalloprotease 10, APLP2 – amyloid precursor-like protein 2, BACE1 – β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1, BDNF – brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BTBD3 – BTB domain containing 3, CDKN2A – cell cycle regulator, GMEB2 – glucocorticoid-sensing factor, hBACE1 – high levels of human β-secretase, Rb1 – retinoblastoma protein, SIRT1 – sirtuin 1, SNX6 – sorting nexin 6, SYN-2 – synaptic phosphoprotein, SYNJ1 – synaptojanin 1, SYNPR – synaptoporin, TGFBI – transforming growth factor, TRIM2 – tripartitemotif-containing 2, VDR – the vitamin D3 receptor, VEGF – vascular endothelial growth factor, 15-LOX – 15-lipoxygenase.

Table II

Expression profiles of miRNAs in AD

We used data search tools to assess the number of dysregulated miRNAs which have been experimentally verified to relate to AD pathology (Table I). There will be more and more evidence about miRNA-AD association over time. From our database 27 dysregulated miRNAs were identified as involved in amyloidogenesis, inflammation, degradation of neurons, neurite differentiation, antiapoptotic, neuronal survival and proliferation, Aβ-induced pathologies, aberrant network activity and synaptic depression.

In our literature many miRNAs are dysregulated in AD and even the same miRNAs in different studies are identified as differently up-regulated or down-regulated (Tables I and II). We used microarray analysis of AD specimens from the candidate studies to assess the implicated miRNAs with comparison to age-matched healthy control specimens. Originally, the studies primarily focused on dysregulation of miRNAs in cortex of AD [5] aimed at finding the pathology of AD. Recently there are still many studies which try to identify primary dysregulation of miRNAs in AD [9, 14, 15]. With the development of AD pathology, more and more studies have focused on dysregulation of miRNAs in blood or CSF of AD aimed at identifying the preclinical phase early [10, 14, 16–18]. In order to provide the first insights into the miRNAs’ different expression between human cerebral cortical gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) in AD, Wang et al. [12] identified a significant number of dysregulated miRNAs in GM and WM of AD brain but those data suggested that patterns of miRNA expression in cortical GM may contribute to AD pathogenetically. Pichler et al. [9] found that miR-7 expression was downregulated in cortex, which correlated with AD amyloidogenesis. But Lukiw et al. [19] and Cogswell et al. [4] separately reported that miR-7 was upregulated in cortex. MiR-9 was also identified as differently dysregulated in AD, which was assessed as downregulated in cortex [9, 15, 20] and in blood [21] but the Zhao et al. [22] study identified upregulation in cortex.

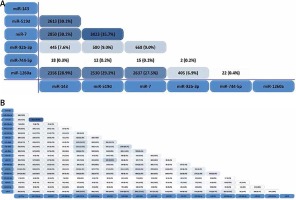

In our bioinformatics analysis, whether in cortex or in blood and CSF, a number of dysregulated miRNAs have been identified as up- or down-regulated in different studies [4, 8–11, 14, 17, 22–26]. These data separately showed overlapping miRNA expression for the first time, which resulted in significant problems (Table II). Even several miRNAs in CSF are reported as upregulated and downregulated targets in AD in the same class [4]. However, none of the studies reported the same up- and down-regulated miRNAs from the same class (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Tabular Venn diagram analysis. Cross-tables show the number and percentage of miRNAs that are in common among studies examining miRNA expression by microarray analysis. A – up-regulation in cortex; B – down-regulation in cortex; C – dysregulation in blood; D – dysregulation in CSF. The number of miRNAs in common to each of the groups is rather. No, that means the common miRNAs in different studies and it reveals that none of the studies reported the same up- and down-regulated miRNAs from a the same class

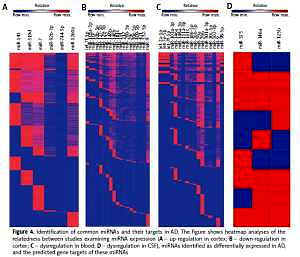

We used clustering to generate a heatmap to visualize the different studies’ relationship for the related set of miRNAs. More specifically, we compared the findings of 15 studies related to cortex, 11 studies related to blood and 7 studies related to CSF by aiming to identify miRNAs in AD. It is still mostly unknown what the biological and clinical distinctions and function are in the up-regulated and down-regulated miRNAs in different tissues. However, dysregulated miRNAs may play a crucial role in the development of AD pathology as biomarkers and it is worth making a re-evaluation of the medical records of the miRNA in these. We analyzed either up- or down-regulated miRNAs coordinately modulated with the disease state and found that they have common functions and partly regulate common pathways. Therefore, we used TargetScan to search the predicted targets of each set of miRNAs and tabulated the number of mRNAs that match to a specific miRNA to perform clustering analysis in order to define how many common mRNA targets there are in different sets of miRNAs.

Preliminary Venny analysis by TargetScan and FunRich tools showed common targets of “Up-regulated miRNAs (miR-143, miR-519d, miR-7, miR-92b-3p, miR-744-5p, miR-1260a)” and “Down-regulated miRNAs (let-7f-5p, miR-103a-3p, miR-107, miR-10b-5p, miR-127-5p, miR-129-5p, miR-132, miR-146b, miR-148b, miR-181c, miR-191, miR-212, miR-26b-5p, miR-29c, miR-30e-5p, miR-409-5p, miR-421, miR-496, miR-532-5p, miR-9)” in cortex (Figure 3), common targets of “dysregulated miRNAs (let-7a-5p, let-7e-5p, let-7f-5p, miR-103a-3p, miR-142-3p, miR-146a, miR-148a-3p, miR-151a-3p, miR-181c, miR-186-5p, miR-26b-5p, miR-29a, miR-29b, miR-301a-3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-502-3p, miR-9, miR-98-5p)” in blood (see above), and common targets of “dysregulated miRNAs (miR-375, miR-125b, miR-146a)” in CSF (see above). Strikingly, heatmap analysis showed several classes of miRNAs that derived from the 28 studies (Figure 4). We used three GO analysis tools – DAVID, FunRich and String – to assess biological functions of coordinately regulated miRNAs with common targets and these data were visualized using bar graphs (Figure 5). Remarkably, our assessment showed that the putative functions of up-regulated miRNAs primarily target the nucleus and down-regulated miRNAs primarily target transcription, DNA-templated (Figure 5). These results of the analysis suggest that up- and down-regulated miRNAs biologically target two diverse molecular mechanisms to affect AD.

Figure 3

Tabular Venn diagram analysis. The cross-table in panel A is based on up- or down-regulated miRNAs that are identified in two or more studies depicted in Figures 2 A and B, and shows the similarities in predicted target genes of up-regulated miRNAs. Panel B shows the same as Panel A for putative target genes of down-regulated miRNAs identified in Figures 2 A and B as having been observed in two or more studies

Figure 4

Identification of common miRNAs and their targets in AD. The figure shows heatmap analyses of the relatedness between studies examining miRNA expression (A – up-regulation in cortex; B – down-regulation in cortex; C – dysregulation in blood; D – dysregulation in CSF), miRNAs identified as differentially expressed in AD, and the predicted gene targets of these miRNAs

Figure 5

Common targets of AD related miRNAs are linked to distinct biological processes. Different classes of common miRNAs associated with AD collectively target distinct gene networks. A – the top 10 functions linked to up-regulated miRNAs. B – the networks of common genes linked to up-regulated miRNAs C – the top 10 functions linked to down-regulated miRNAs. D – the networks of common genes linked to down-regulated miRNAs

Discussion

More and more studies have demonstrated that miRNAs play a crucial role as candidate biomarkers of AD for early diagnosis or new drug targets, which take part in posttranscriptional regulation of expression of various genes. The benefit of biomarkers is to detect the pathology, especially since it is not present in the preclinical phase early. A miRNA may have hundreds of different mRNA targets; at the same time a target might be regulated by a combination of multiple miRNAs [27]. In AD dysregulated miRNAs have been identified to be involved in amyloidogenesis, inflammation, tau phosphorylation, apoptosis, synaptogenesis, neurotrophism, neurons degradation, innate immune signaling, NF-κB signaling, and activation of cell cycle entry.

The name “Alzheimer’s disease” pertains to the underlying pathological features: neuronal atrophy, synapse loss and the progressive accumulation of senile plaques. These plaques are composed of various amyloid β (Aβ) peptides, including amyloid precursor protein (Aβ 40 and Aβ 42) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (hyperphosphorylated tau protein) [28]. Cerebrovascular deregulation is seen as a contributor to AD [29], providing a better understanding of the physiological mechanisms of AD in dementia, which helps us to focus on the treatment of neurovascular repair. MiRNAs related to cerebrovascular deregulation may play an important role in AD, which helps us collect comprehensive data to assess miRNAs in AD.

The pathological features are, along with synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory; neuronal survival and apoptosis; adult neurogenesis which continues in the adult hippocampus; regulation of neural processes and structural plasticity; inflammation; and amyloid β (Aβ) production and toxicity. Increasingly, numerous miRNAs have been found to play crucial roles in regulating Aβ production in the process of AD [30].

AD markers mostly mentioned are tau and Aβ, which are used to identify and understand the mechanisms involved in the etiopathogenesis of AD. Amyloidogenesis reflects the pathological features of AD and plays a remarkable role in AD progression. Many studies have indicated that dysregulation of miRNAs has been linked with tau and Aβ pathogenic functions in AD. Until now, many studies have implicated miRNAs in amyloidogenesis, especially as a central factor in AD, such as miR-7 [9, 22], miR-9 [9, 15], miR-26b [14, 30], miR-34a [31], miR-98-5p [32], miR-106 [33], miR-128 [34], miR-132 [35], miR-144 [36], miR-146a [37], miR-153 [38], miR-181 [39], miR-211-5p [40] and miR-339-5p [41]. And the prefibrillar form of soluble Aβ also impairs synaptic function and is the major cause of cognitive defects associated with AD. For instance, some studies reported that miRNAs including miR-125b [22, 42, 43], miR-134 [44], and miR-384 [45] may dysregulate Aβ to cause synaptic dysfunction.

Neuronal differentiation is also a part of AD pathology including neuronal survival and apoptosis, morphogenesis, adult neurogenesis, regulation of neural processes and structural plasticity. Several miRNAs have been identified as related to neuronal differentiation including miR-26b [14, 30], miR-29 [46–49], miR-34b/c [50, 51], miR-107 [52, 53], miR-124 [54], miR-128 [34], miR-137 [55], miR-193b [56], miR-210 [57], miR-211-5p [40] and miR-384 [45].

Microglia are a kind of immunocompetent cells in the central nervous system (CNS), which accumulates at amyloid β plaques in AD as activated microglia. Several miRNAs may preferentially block many cellular anti-inflammatory proteins’ translation that could drive a pro-inflammatory response [58]. Key pro-inflammatory (miR-155 [19, 22], miR-27b [12], miR-326 [14]), anti-inflammatory (miR-9 [9, 15], miRNA-125b [43], miR-124 [5, 12, 25], miR-132 [35], miR-146a [19, 37], miR-21 [12], miR-223 [12]), and mixed immunomodulatory (let-7 family [8, 12, 14, 16, 24, 59, 60]) miRNAs regulate neuroinflammation in AD. In the absence of a pro-inflammatory response, inflammasome-mediated collagen synthesis could not be induced. MiRNA-146a was reported [19] to be related inflammation in AD as an NF-κB-regulated pro-inflammatory miRNA which targets the 3’-UTR of complement factor H (CFH) in human monocytes.

Bioinformatics analysis of quantitative expression data was performed, identifying a variety of miRNAs as up- or down- regulated in AD cortex, blood and CSF compared to age-matched controls. Increasingly many studies focus on miRNA dysregulation not only in AD brain but also in AD blood and CSF and have yielded better convergence of the database to improve the detection methods for miRNAs. In spite of inconsistent up- or down-regulated miRNAs, it is a research trend to find the key biomarkers in the preclinical phase early.

Bioinformatic analysis was used to compare gene ontology terms and to assess whether the common targets of representative coordinately regulated miRNAs play a key role in larger biological programs and regulatory networks. We separately listed the top 10 functions of two groups of miRNAs from our database (Figure 5) to show whether these miRNAs have the same predicted targets. Then, we resorted to Target Scan to find and tabulate potential target mRNAs. This analysis revealed that six common miRNAs that are reported as up-regulated in AD cortex (i.e., miR-143, miR-519d, miR-7, miR-92b-3p, miR-744-5p, miR-1260a) in these studies have many targets in common (Figure 4). Similarly, twenty common down-regulated miRNAs observed in these studies (i.e., let-7f-5p, miR-103a-3p, miR-107, miR-10b-5p, miR-127-5p, miR-129-5p, miR-132, miR-146b, miR-148b, miR-181c, miR-191, miR-212, miR-26b-5p, miR-29c, miR-30e-5p, miR-409-5p, miR-421, miR-496, miR-532-5p, miR-9) also have a shared set of targets (Figure 4). But in AD blood and CSF there are not consistent up- or down-regulated miRNAs in different studies. We listed the common miRNAs related to AD (let-7a-5p, let-7e-5p, let-7f-5p, miR-103a-3p, miR-142-3p, miR-146a, miR-148a-3p, miR-151a-3p, miR-181c, miR-186-5p, miR-26b-5p, miR-29a, miR-29b, miR-301a-3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-502-3p, miR-9, miR-98-5p in blood and miR-375, miR-125b, miR-146a) but the results of dysregulation are not consistent (Figure 4).

Divergence of miRNA dysregulation may be caused by several factors: 1) miRNA regulation altered in different stages of AD is different. If each study only compared the same phase of AD with healthy controls, there should be the same results, but these studies compared all phases of AD with healthy controls, leading to the opposite results. The same miRNA can target different genes to cause the pathology of AD. In turn, the impacts of genes on miRNAs cause different miRNA regulation. Onset of miRNA functional deficits in the different stages of AD may be different. 2) Different miRNA detection may produce different results because of sensitivity and specificity. 3) The insufficient samples led to weakening of statistical characteristics and resulted in different data or unclear mechanisms of AD. So the essential question remained unaddressed: whether these miRNAs are upregulated or downregulated in different tissue of AD and whether specific or early perturbations of miRNA regulation cause the link to relevant mechanisms of AD pathology or only nonspecific epiphenomena of neurodegeneration. The further study must overcome the challenges posed by studies with limited patient sample sizes. Cause and effect are difficult to establish in our assessment that many miRNAs were misregulated and it is suggestive that dysregulation were not merely consequences of pathology. Challenges for further research are posed by studies with different tissues and limited patient sample sizes. Taken together, both up- and down-regulated miRNAs in AD different specimens seem to coordinately suppress a common set of genes. We used GO terms to get larger biological programs and regulatory networks from our obtained data about representative coordinately regulated miRNAs’ common targets in cortex. This analysis resulted in the striking finding that shared miRNAs detected in common up-regulated miRNAs primarily target the nucleus and common down-regulated miRNAs primarily target transcription, DNA-templated. In the nucleus, miRNAs regulate gene expression by binding to the targeted promoter sequences and affect either the transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) or transcriptional gene activation (TGA) [61]. Distinct common sets of mRNAs link the respective targets and broader biological programs, which may indicate that AD may be guided by effects of proteins required for gene expression.

Most of the mRNAs targeted by miRNAs are transcription factors (TFs), which focus on regulating plant growth and development [62]. The observation is consistent with a relatively simple molecular framework for miRNA-mediated nerve degeneration. Dysregulated miRNAs play an important role in progression of AD, regardless as to whether miRNAs are up-regulated or down-regulated. Modulation of any processing by miRNAs can achieve a ‘double-negative principle. For example, up-regulated miR-143, miR-519d, miR-7, miR-92b-3p, miR-744-5p, miR-1260a could upregulate TFs or other positive proteins and lower expression of negative proteins, and then lead to high gene expression, which may be protective of CNS. Furthermore, down-regulated let-7f-5p, miR-103a-3p, miR-107, miR-10b-5p, miR-127-5p, miR-129-5p, miR-132, miR-146b, miR-148b, miR-181c, miR-191, miR-212, miR-26b-5p, miR-29c, miR-30e-5p, miR-409-5p, miR-421, miR-496, miR-532-5p, miR-9 could lower expression of positive TFs or raise expression of negative TFs, and then lead to CNS degenerative gene overexpression or protective gene under-expression. But the molecular mechanisms are still mostly unclear. We speculated that perturbations in miRNA-TF regulatory networks during successive stages of AD may be caused by broad ranging pleiotropic effects.

AD activity remains largely enigmatic because it is multi-factorial, with a range of processes compromised. However, implicated miRNA pathways, which control transcription, cell junction and ATP binding kinase-related signaling pathways, have been increasingly identified. In addition they can lead to amyloidogenesis, inflammation, tau phosphorylation, apoptosis, synaptogenesis, neurotrophism, neuron degradation, and activation of cell cycle entry. According to screening of AD-related miRNAs, we can identify the preclinical phase early, which provides an important time window for therapeutic intervention. We can better understand the unknown mechanisms of progressive AD pathology. It is unclear which miRNAs are primarily susceptible to AD through AD-miRNAs screening, but rather it indicates AD activity more easily than would otherwise have been the case. There are pronounced clinical implications for assessing the risk miRNAs related to AD. Our study comprehensively reviewed the miRNAs’ dysregulation in different tissues of AD, and it can be used to delay disease progression. Recently more and more studies have tried to identify possible miRNA therapeutic targets. However, it is a long way to use the predicted therapeutic benefits of targeted treatments in clinical practice without clinical trials, which requires the safety and efficacy of targeted drugs.

There are advantages and limitations of this study. Although we conducted a comprehensive search through multiple databases for selection and appraisal of candidate AD miRNA biomarkers by independent pairs of reviewers, including several hypotheses for the role of miRNAs in AD, our study suffered several important limitations: 1) Divergence of miRNA dysregulation may be caused by the different phases of AD. If each study only compared the same phase of AD with healthy controls, there should be the same results, but these studies compared all phases of AD with healthy controls, leading to the opposite results. It may be because the insufficient samples led to weakening of statistical characteristics and resulted in different data. So it is better to collect larger samples to assess the regulation of miRNAs in AD pathogenesis. There may be publication bias because of inadvertently omitting unpublished studies with negative results. 2) There are other unknown biological processes caused by miRNA dysregulation in AD. The further study will be designed well to assess the roles of miRNAs in the different phases of AD and it is better to evaluate the dysregulation of microRNAs related to AD to reveal the underlying complex mechanisms. Therefore, in the future we need to renew the miRNA-AD database.

In conclusion, we provided a comprehensive genome scale description of disease-altered expression of miRNAs in AD brain, blood and CSF. Through our search and assessment of miRNA targets, we identified what miRNAs may correlate with useful biomarkers of AD and be referred to novel pathways contributing to AD pathogenesis. In addition to dysregulation of miRNAs in AD brain, there are quantitative changes in miRNA expression in AD blood and CSF that provide initial hope to provide accessible biomarkers to aid diagnosis of AD. In the future, it is advisable to focus on the relationship between the miRNA changes in blood and CSF and AD-specific signaling molecules and aspects of these changes specific to AD.

Even though hundreds of miRNAs have been identified as dysregulated, it is unknown which miRNAs are the primary biomarkers. Bioinformatics analysis of dysregulated miRNAs in AD reveals a relationship in miRNA signatures of different tissues. We identified that miRNAs target TFs to directly control gene expression, which is a unique miRNA signature, while the other studies indicate different miRNAs that control nucleus functions. It is crucially important to diagnose AD combined with dysregulated miRNA profiles and other standard diagnostic tools at the preclinical stages. Additionally, miRNA profiling from brain, blood or CSF samples for future research will achieve the same AD diagnosis of the same patient.