Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a widespread chronic disease characterized by progressive articular cartilage degeneration, leading to joint dysfunction, pain, and disability [1]. The prevalence of this debilitating syndrome is escalating with the combined impact of aging, mounting obesity rates, and rising joint injuries in the global population, with current estimates of approximately 240 million affected individuals worldwide [2, 3].

The increasing incidence of OA represents a significant and growing public health concern, imposing a substantial burden on affected individuals and healthcare systems, with wider socio-economic costs. The recommended pharmacological management of OA involves non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, with other medications such as acetaminophen, glucosamine, and opioids commonly used in clinical practice [4–6]. Nutraceuticals such as calcium, hyaluronic acid, glucosamine, and omega-3 fatty acids are also considered for their potential to alleviate pain and inflammation [7]. Cheese, with its high concentration of essential vitamins, minerals, calcium, and proteins recognized for their essential role in skeletal muscle and bone health, is of particular interest among these approaches [8–10]. Additionally, cheese has demonstrated promising biological properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, antimicrobial, and analgesic activity, which could positively affect OA-related inflammatory, biomechanical, and metabolic factors [10]. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that some studies have reported higher cheese intake associated with increased hip OA risk, possibly due to the positive correlation between hip bone mineral density and dairy intake [11–13]. Notwithstanding, the literature regarding the potential detrimental or advantageous impact of cheese intake on OA remains uncertain and restricted, with inconsistent outcomes observed in previous investigations.

In a cross-sectional study of 655 Turkish individuals, reduced milk intake was found to be associated with an increased likelihood of symptomatic knee OA, while no significant associations were observed for either cheese or yogurt intake [14]. In a prospective study of 2481 participants from the Osteoarthritis Initiative, women with frequent milk intake had a reduced rate of OA progression, while women with the highest cheese intake had a higher rate of progression compared to those with no cheese consumption [15]. Similarly, a prospective cohort study found that increasing dairy product intake was associated with a higher risk of total hip arthroplasty for OA in men, but not in women [16]. However, it is crucial to note that these observational studies are inherently limited by the possibility of confounding factors and reverse causality [17, 18]. The link between cheese intake and OA liability, for instance, may be influenced by adiposity and metabolic factors. In contrast, MR studies that utilize the random inheritance of genetic variants present in the germline, which are non-modifiable, are less prone to confounding and could estimate the causal relationship between cheese intake and OA.

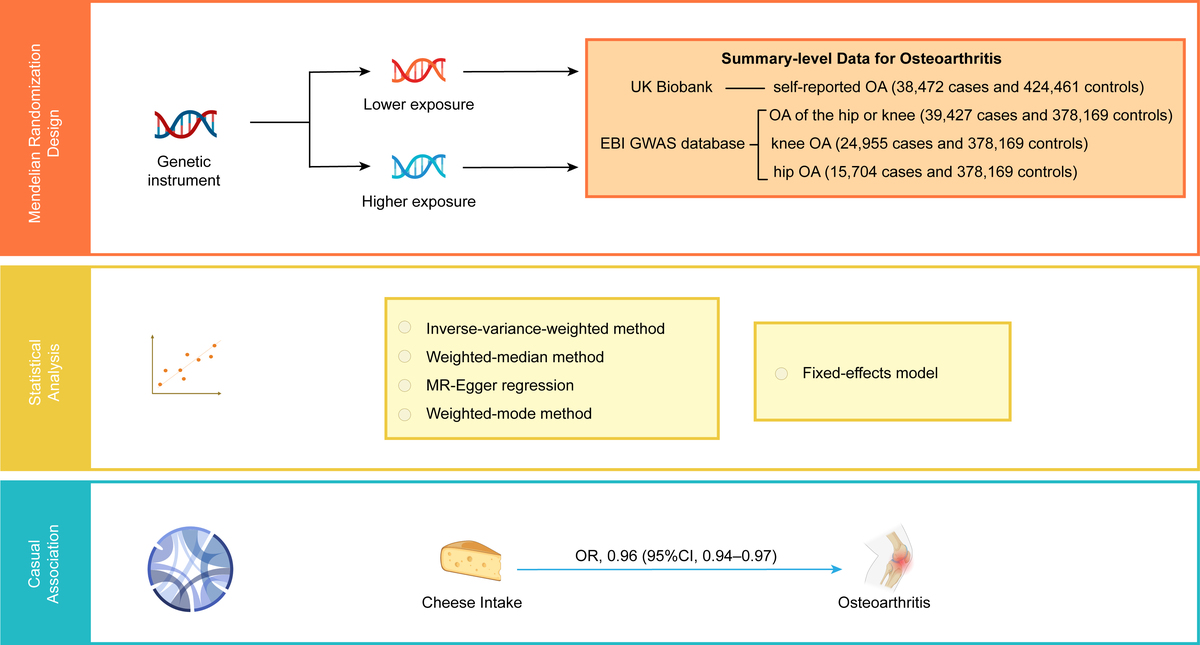

Mendelian randomization (MR) has emerged as a compelling and robust epidemiological approach to infer causality between genetically predetermined exposure factors and clinical outcomes, utilizing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables (IVs) [19]. A salient feature of MR is that it capitalizes on the principle of Mendelian inheritance, where alleles are randomly allocated during fertilization, thereby attenuating the deleterious impact of confounding and reverse causality that are frequently encountered in conventional observational studies, and providing more credible results. In this investigation, we employed a two-sample MR analysis to explore the causal association between cheese consumption and OA in the European population, utilizing data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS).

Material and methods

Study design

We conducted a meticulous two-sample MR investigation to examine the relationship between genetic liability for cheese intake and OA, including self-reported OA, hip or knee OA, and hip OA, utilizing SNPs as instrumental variables (IVs). Three fundamental hypotheses were rigorously confirmed during the whole process to ensure the validity of our findings: (1) the correlation hypothesis, which assumes that the IVs are closely associated with cheese consumption; (2) the exclusion hypothesis, which posits that the IVs are not associated with OA unless via cheese consumption; and (3) the independence hypothesis, which requires that the IVs are not correlated with any potential confounding factors. To maintain ethical standards, we used data obtained from pre-existing studies that were granted ethical approval and informed consent by their respective original authors. Additionally, our research was granted ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, with the reference number KY-Q 2021-244-01.

Data sources

In the present investigation, summary statistics of GWAS predominantly involving European participants were used to estimate the causal relationship between cheese consumption and OA. The GWAS data for cheese intake were derived from a large cohort study involving approximately 500,000 individuals performed by the UK Biobank (http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank/) [20]. Participants in the cohort were invited to the local evaluation center for data collection using a touch-screen questionnaire or standardized anthropometry. Participants’ intake of cheese as an exposure factor was extracted by a questionnaire asking about the frequency of cheese intake. The participants were asked, “How often do you eat cheese? (Include cheese in pizzas, quiches, cheese sauce etc.) (Please provide an average considering your intake over the last year).” Participants could choose from the following answers: never, less than once a week, once a week, 2–4 times a week, 5–6 times a week, once or more daily, do not know, and prefer not to answer. In total, 451,486 European participants’ cheese intake data were obtained. The GWAS summary statistics have been included in the IEU OpenGWAS database and are readily available for researchers to download (GWAS ID: ukb-b-1489) [21]. To define osteoarthritis cases, we used the self-reported status established during an interview with a nurse (Field 20002; Initial assessment visit) and the Hospital Episode Statistics ICD10 primary and secondary codes [22]. The primary outcome in this study was the self-reported OA. The summary-level data for self-reported OA was also obtained from the large GWAS conducted by the UK Biobank, enrolling 462,933 participants of European ancestry (38,472 cases and 424,461 controls). Moreover, the secondary outcomes were specific diagnosed knee OA (24,955 cases and 378,169 controls) and hip OA (15,704 cases and 378,169 controls), and OA of the hip or knee (39,427 cases and 378,169 controls), which were sourced from the EBI GWAS database. The GWAS IDs for the outcomes are as follows: ukb-b-14486 for Self-reported OA, ebi-a-GCST007092 for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, ebi-a-GCST007090 for knee OA, and ebi-a-GCST007091 for hip OA. Table I provides a comprehensive depiction of the characteristics of each OA.

Table I

Description of included traits

Selection and validation of SNPs

We adopted a rigorous selection process for the instrumental variables (IVs) used in the MR study. Firstly, we selected SNPs that displayed a genome-wide significance level of p < 5 × 10–8, indicating a strong statistical association with cheese consumption. Secondly, we tested the linkage disequilibrium (LD) to assess the independence among the selected SNPs, conducting a clumping protocol to extract independent SNPs within a 10,000 kb window size and R2 < 0.01 threshold. Third, we calculated the F-statistics to assess the efficacy of each IV and excluded weak instruments with a threshold of F > 10, minimizing the impact of potential bias. Finally, we harmonized the SNPs of exposure and outcome by removing or adjusting SNPs with inconsistent alleles according to their alleles and allele frequencies, to ensure they had corresponding alleles.

Mendelian randomization analyses

This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization Statement (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34698778/). In this investigation, we applied the inverse variance weighting (IVW) method as the primary analytical tool to infer the plausible causal link between cheese intake and OA. We also utilized three other effective methods – MR-Egger, weighted median, and weighted mode – to comprehensively evaluate the possible relationships. Moreover, to provide a summary measure for the effect of genetically determined cheese intake, including all SNPs with genome-wide significance for cheese intake, we combined weighted estimates utilizing a fixed-effects meta-analysis model.

The IVW method, which utilized the inverse of the variance of outcomes as weight and assumes no intercept, can generate impartial causal associations under the ideal assumption that all selected genetic variations have valid IVs without pleiotropy [23]. On the other hand, the MR-Egger analysis can infer the corrected causal effect and provide estimates without bias, even if not all selected IVs are valid. However, it might be with lower statistical power due to the significant influence of outlying genetic variables [24]. The weighted median method could provide precise and robust causal association estimates as long as at least 50% of the information from valid instruments is available [25]. In addition, the weighted mode can be trustworthy when the largest subset of instruments with similar causal effects is valid.

Sensitivity analyses

In an MR analysis, pleiotropy posed a potential source of bias and may result in an overestimation of the causal effect. To assess the average horizontal pleiotropy, we utilized the MR-Egger regression intercept. When MR-Egger intercepts a significant difference from zero, it suggests that not all IVs are valid. Furthermore, we employed the MR-Egger and IVW approaches to evaluate heterogeneity among the selected SNPs by computing the Cochran Q statistics. The results showed that there was no statistically significant heterogeneity (p > 0.05). In addition, we utilized the I2 metric to quantify heterogeneity. The values of I2 ranged from 0% to 100%, where higher values indicate greater heterogeneity. Lastly, we performed a leave-one-out analysis to identify potential outliers that may strongly influence the causal inference by sequentially removing each SNP and conducting the IVW method on the remaining SNPs.

The odds ratio (OR) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were presented to depict the causal link between cheese consumption and OA. Forest plots, scatter plots, and funnel plots were utilized to visually portray the results of the MR investigation. The TwoSampleMR package in the R program (version 4.1.0) was used to explore the effect of cheese intake on OA.

Results

SNP selection and validation

Table I presents the foundational features of the studies encompassed in the MR analysis. In summary, the studies utilized in this MR investigation were derived from the European population and were published within the period of 2018–2019. The number of SNPs related to cheese intake was 9 851 867, and those for self-reported OA, osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, knee OA, and hip OA were 9 851 867, 3 0265 359, 29 999 696, and 29 771 219, respectively.

Causal associations between cheese intake and osteoarthritis

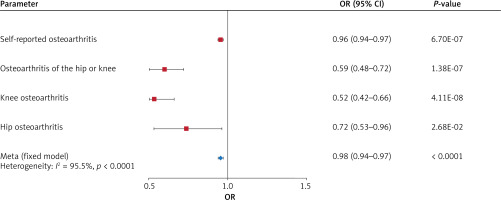

As portrayed in Figure 1, genetically predicted cheese intake was found to be inversely correlated with self-reported OA (odds ratio (OR) = 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.94–0.97, p = 6.70 × 10–7), OA of the hip or knee (OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.48–0.72, p = 1.38 × 10–7), knee OA (OR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.42–0.66, p = 4.11 × 10–8), and hip OA (OR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.53–0.96, p = 0.0268) by the IVW method. With a fixed-effect model, pooled meta-analysis also demonstrated an inverse causal relationship between cheese intake and OA (OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.94–0.97, p < 0.0001) (Table II).

Table II

Pooled meta-analysis association of cheese intake with osteoarthritis

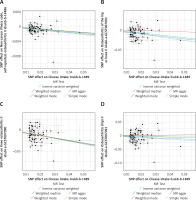

Apart from the primary IVW analysis, we employed various supplementary analytical methods, including the weighted median, MR-Egger, and weighted mode methods, to validate the accuracy of our results. The OR estimates obtained from the weighted median of self-reported OA (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.95–0.98, p = 1.124 × 10–4), OA of the hip or knee (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.54–0.84, p = 4.272 × 10–4), and knee OA (OR = 0.54; 95% CI = 0.41–0.70; p = 3.457 × 10–6) were consistent with those derived from the IVW analysis, whereas no significant correlations were observed in the MR-Egger and weighted mode analyses. With respect to hip OA, the weighted median, MR-Egger, and weighted mode analyses did not demonstrate any significant association (Table III). Additionally, the findings of the study were graphically represented by the forest plot (Figure 2) and the scatter plot (Figure 3).

Table III

Mendelian randomization for the association of cheese intake with osteoarthritis

Figure 1

Forest plot showing the main Mendelian randomization estimates for the association of cheese intake with osteoarthritis (OA)

Sensitivity analyses

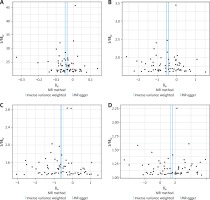

The intercepts of self-reported OA (MR-Egger regression intercept = –1.1 × 10–4, p = 0.85), OA of the hip or knee (MR-Egger regression intercept = 0.002, p = 0.778), knee OA (MR-Egger regression intercept = –6.00 × 10–4, p = 0.942), and hip OA (MR-Egger regression intercept = –0.0024, p = 0.824) obtained from the MR-Egger regression analysis revealed no evidence of genetic pleiotropy in our investigation (Table III). Additionally, the funnel plot displayed in Figure 4 suggested that horizontal pleiotropy did not influence the findings. Cochrane’s Q test was performed to assess heterogeneity, and significant findings were obtained from the IVW and MR-Egger analyses (Table III). Consequently, to minimize the impact of heterogeneity, we performed an IVW meta-analysis with a fixed-effects model. Moreover, we conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, as illustrated in Figure 5, which demonstrated that no single SNP was driving the results.

Discussion

Through our stringent two-sample MR analyses, we obtained compelling evidence of a causal inverse association between cheese intake and OA, including self-reported OA, OA of the hip or knee, knee OA, and hip OA. In addition, to ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted multiple reliable sensitivity analyses to indicate that the observations were not influenced by pleiotropic effects.

Due to the significant prevalence of OA and the common consumption of cheese, it is essential to explore the potential relationship between cheese intake and OA. However, prior observational studies have provided inconsistent findings. In contrast to our findings, a previous cross-sectional study involving 655 participants reported that the frequency of knee OA was notably lower among individuals who consumed milk and tea but not cheese [14]. Moreover, a study including 2148 participants found that milk consumption might reduce OA progression in women, while cheese intake could increase knee OA progression [15]. The high saturated fatty acid included in cheese might contribute to OA pathogenesis [26]. A study also suggested that increased saturated fatty acid intake may lead to a higher incidence of bone marrow lesions, which could predict knee OA progression [27]. On the other hand, our findings were in accordance with a previous cross-sectional investigation that detected a negative relationship between cheese consumption and OA prevalence. The investigation found that a greater intake of full-fat dairy and Dutch cheese was linked with a lower incidence of clinical knee OA in the Dutch population [28]. However, the observational investigations also included some limitations, such as ethnic homogeneity, sample size, and inadequate information, which might result in biases and unreliable inferences. Therefore, more rigorous investigations are needed to provide stronger evidence and guidance for clinical practice. Hence, we conducted an MR analysis to comprehensively investigate the potential causal relationship between cheese consumption and OA.

Contrary to most prior investigations, this MR analysis revealed causal inverse associations between cheese intake and OA. Several plausible explanations for this discrepancy have been given. For instance, Kaçar et al. found that lower education was associated with a higher risk of knee OA [14]. People of higher education might be more likely to consume cheese and adopt a healthier lifestyle, thus reducing their exposure to multiple health risks. Additionally, the previous studies relied on self-reported cheese intake, which could lead to inaccurate long-term cheese consumption measurements due to underlying misclassification of habitual cheese intake. Furthermore, it should be noted that the distribution of cheese consumption among the general population is not random and might be affected by a variety of factors, including cultural preference, population structure, age stratification and gender. These factors should be taken into account when interpreting the results of prior observational investigations. Our analysis highlighted the significance of carefully accounting for multiple confounding factors when investigating the association between cheese intake and OA. The implications of our investigations might be significant for guiding the development of dietary recommendations and public health policies.

The potential advantageous influence of cheese consumption on OA could be explained by a multitude of mechanisms. Firstly, micronutrients included in cheese, such as vitamin D, phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium, are critical for bone health [29]. Inadequate intake of vitamin D has been linked to the progression of knee OA [30]. Secondly, it was previously thought that dairy products contributed to inflammation [31], but recently abundant evidence has disproved this point. On the contrary, whole-fat dairy products and dairy fats have been found to have no effect or to be inversely associated with inflammation [32, 33]. An analysis of nutritional intervention trials conducted on overweight subjects revealed that the intake of dairy products did not lead to any harmful impacts on inflammatory biomarkers [34]. Additionally, in a randomized controlled trial involving individuals with mild systemic inflammation, intake of a combination of low-fat and high-fat dairy products did not trigger any unfavorable effects on inflammation [35]. Hence, it is plausible that the anti-inflammatory properties of cheese might have a crucial impact on the prevention of OA. Moreover, the peptides contained in cheese possess antimicrobial, antioxidative, immunomodulatory, and opioid agonistic and antagonistic properties [36], which may contribute to knee OA prevention. Nevertheless, human statistics in this regard are currently lacking. Finally, because dietary lipids impact the bioavailability of fat-soluble nutrients such as vitamins A, D, E, and K, phytosterols, and carotenoids, consumption of fatty foods such as cheese enhances the intake of fat-soluble nutrients from other concomitantly consumed foods, which might clarify the negative relationship between cheese consumption and OA [28].

The research has several strengths. Firstly, this was the first investigation to evaluate the causal relationship between cheese intake and OA using MR analysis. In the investigation, the random distribution of SNPs at conception can substantially diminish biases attributable to possible confounding factors and reverse causation. Secondly, the utilization of summary-level statistics with a vast number of cases greatly improved our ability to identify causality. In addition, the data we analyzed in our study were restricted to individuals of European ancestry, reducing the potential for population stratification bias to influence our findings. Lastly, it should be emphasized that our findings highlighted the potential benefits of cheese consumption for the management of OA.

Notwithstanding, this study has some limitations that warrant attention. Firstly, the study subjects were exclusively of European ancestry; thus, the applicability of our findings to other ethnicities, such as Africans, should be approached with caution. Secondly, it is worth noting that our study did not explore the potential impact of cheese diversity and quantity on OA, as we lacked data on the specific types and amounts of cheese consumed by participants. Additionally, as the original GWAS did not provide information on whether cheese was ingested with another diet, this might have had an impact on the observations. Thirdly, measurement errors may occur with the diet questionnaire that was used to gather data on cheese consumption. Fourthly, the risk of false positives could be elevated by the possibility of sample overlap between the populations of the EBI GWAS database and the UK Biobank database. Fifthly, even with multiple sensitivity analyses, potential bias caused by SNP heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy cannot be entirely ruled out.

In conclusion, our MR investigation revealed genetic evidence of an inverse correlation between cheese intake and OA, which included self-reported OA, OA in the hip or knee, knee OA, and hip OA. Specifically, based on our results, we recommend that patients with or at risk for osteoarthritis moderately increase cheese intake to reduce the incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Moreover, the finding had important implications for dietary guidelines and food policy, as it suggested that dietary interventions, especially increasing cheese intake, may be effective in the prevention of OA, and should be promoted in more regions. Further randomized controlled trials and cohort studies are needed in the future to confirm the causal link between cheese intake and OA.