The primary objective of the pharmacy profession is to safeguard public health. Pharmacists are considered the most accessible health care professionals to patients [1–3], as indicated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and others [4] who highlight the pharmacists’ pivotal role in health promotion and education, particularly in the context of community health campaigns.

A concerning trend manifests in the declining number of pharmacists employed in pharmacies. For instance, in Poland, data from the Polish Association of Pharmaceutical Employers, in conjunction with the Statistics Poland reveals an average of 1.85 pharmacists per pharmacy. This average varies across individual provinces, ranging from 1.43 to 2.22. Notably, the average across the European Union countries stands at 2.40 pharmacists per pharmacy [5].

The pharmacist education system exhibits a considerable variation across different countries. Despite the adoption of the Bologna Declaration [6] and the establishment of the European Higher Education Area [7] designed to standardise regulations while respecting the autonomy of individual countries, substantial differences persist in pharmacy education programmes and practice between the countries [8, 9]. As part of the Bologna Declaration, Poland implemented a system of transparent and comparable degrees. Moreover, the ECTS (European Credit Transfer System) [10] system was enhanced and a more uniform system allowing for the employment of graduates was introduced in line with EU Directive 2005/36/EC [11]. The directive serves as a foundational framework for quality assurance in vocational education and training [12].

The main objective of the article is to describe the structure and curriculum of the pharmacy profession in Poland. These principles are then compared with the current pharmacist education system in place in the UK. After taking into account the relevant guidelines by the FIP (International Pharmaceutical Federation), proposals for improving the education of pharmacists within the Polish educational system have been formulated. These proposed changes are aimed at increasing the quality of patient care within the health care system in Poland.

Standards of pharmacy education in the Polish educational system

One of the paramount legal frameworks in Poland regulating university teaching is the Law on Higher Education. This act describes a dichotomous division within the higher education system, categorising studies into first/second cycle studies and single master’s studies, which encompasses pharmacy [13].

Another pivotal document is the regulation of the Minister of Science and Higher Education, outlining educational standards for pharmacists [14]. In the Polish pharmacy education system, the program is defined as a uniform master’s degree spanning no less than 11 semesters. The curriculum entails a minimum of 5300 teaching and placement hours, with 330 ECTS credits required.

Given the practical orientation of pharmacy studies, statutory requirement mandate a six-month apprenticeship in a community pharmacy, with an option to complete part of it in a hospital setting, following the preparation and defence of the master’s thesis, integral to the education process.

According to the regulations of the Minister of Science and Higher Education, pharmacy students are required to complete a minimum of 4810 h of classes covering the biomedical and humanities foundations of pharmacy, physicochemical foundations of pharmacy, analysis, synthesis and technology of drugs, biopharmacy and the effects of drugs, pharmacy practice, and methodology of scientific research. The inclusion of 1280 h of professional practice, encompassing both summer internships and a six-month professional apprenticeship, plays a crucial role in the holistic education of pharmacists.

General standards for pharmacy education in the United Kingdom

The educational framework for pharmacists in the UK diverges from the Polish Master of Pharmacy education system, primarily due to the autonomy of the General Pharmaceutical Council, serving as the independent regulatory body for pharmacy practice. Attainment of a Master of Pharmacy degree necessitates completion of education at a university accredited by this regulatory body.

With a paramount focus on patient safety and public health, the pharmacy education process in the UK adopts a “spiral curriculum”. This curriculum incorporates progressive teaching methodologies that address scientific and professional concepts in an increasingly intricate manner, tailored to the individual’s knowledge and comprehension levels [15, 16].

Assessment of the practical skills possessed by the pharmacist encompasses various aspects, including the identification and utilisation of appropriate diagnostic tools and examination techniques to promote health, recognition of inappropriate health behaviours, and instruction on the effective and safe use of medicines. This extends to the analysis of prescription validity, clinical evaluation of prescribed medicines, and the critical aspects of designing, monitoring and modifying prescribed pharmacotherapy to optimise health outcomes. Effective communication with patients regarding prescribed medications and collaboration with prescribers to enhance patient treatment are deemed crucial [15].

A pharmacy course of study in the UK spans a duration of 4 years, culminating in an MPharm in Pharmacy. The curriculum mandates the completion of a mandatory minimum 12-month placement, most commonly in a community or hospital pharmacy. Completion of this foundation year is followed by the national examination, carried out by the General Pharmaceutical Council. Attaining a passing grade in this examination enables the trainee to practice as a pharmacist [17]. The UK pharmacy curriculum guidelines, in terms of teaching, largely follow the European recommendations. Throughout the 4-year education process, students are required to complete a minimum of 3000 h of coursework directly related to pharmaceutical subjects.

International Pharmaceutical Federation Guidelines

The International Pharmaceutical Federation, in collaboration with the World Health Organisation (WHO) and UNESCO [18], is actively shaping a needs-based model for pharmacist education within a global quality assurance framework. According to FIP, pharmacists bear significant responsibility for ensuring the safe, effective and responsible use of medicines by patients, with the primary objective of optimising therapeutic outcomes [19]. FIP recommends that the competencies of pharmacists can be formulated into a framework that supports the development of practitioners within a unit, enabling effective and sustainable performance. The practitioner development framework, characterised by a structured set of competencies is gaining popularity in professional education, driven by the need for transparency in the training, development and recognition of health professionals [20]. The routine use of competencies in professional development, as evidenced in medicine [21, 22], where the global competency framework was first developed, serves as a precedent.

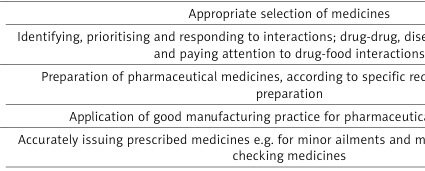

FIP defines four main groups of competences, namely pharmaceutical public health, pharmaceutical care, organisation and management, and professional (Table I).

Table I

Pharmacist competences according to the International Pharmaceutical Federation. Source: own development based on Alhaqan A, Bajis D, Mhlaba S. FIP Global Competency Framework v. 2, 2020.

This framework serves as a foundation for the development of educational programs, emphasising the ability to apply pharmaceutical care from the initial stages of study [22].

Proposals for improving the education of pharmacists within the higher education – system reconstruction

Despite the commitment of both Poland and the UK to the principles of the Bologna Declaration, substantial differences persist in the teaching models of these countries. Discrepancies are evident in the duration of pharmacist training, the number of hours of pharmacy practice (which in the UK is integrated in the training from the first year of study), and the flexibility of training in the UK compared to the fixed curriculum in Poland.

The shift towards curriculum reform is a long-term project and its success depends on several factors, such as the current state of the curriculum, local culture and support from senior management. The recommended changes cover the previously presented areas of education according to FIP, including in particular the scope of soft skills, enabling effective communication with both patients and medical staff in order to best solve clinical problems. Complexity arises because the curriculum reform affects not only the teaching staff but the entire academic community [23].

We propose that a comprehensive strategy consisting of three main phases be imperative for successful curriculum reform. The first phase involves scanning, analysing and diagnosing the current environment and situation. The second phase entails comparing and contrasting different solutions to make strategic and innovative choices aligned with the vision. The third phase focuses on implementing solutions to transform the adopted strategy into action, steering the curriculum towards the envisioned changes.

Conclusions

Recognising the numerous advantages that the optimal utilisation of pharmacists in health care delivery can bring to society, many countries have undertaken or are planning significant transformations in pharmacy education.

In the context of Poland, despite over two decades of European Union membership, the role of pharmacists remains predominantly confined to dispensing medicinal products, lacking a well-established presence in pharmaceutical care and patient health outcomes. Consequently, changes in the teaching system of Polish pharmacists will not only impact the development of this professional group, but will predominantly contribute to improving the quality of patient care.