Introduction

In December 2019, an unknown pneumonia spread amongst a group of people in Wuhan, China, now termed as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). COVID-19 patients were reported with a cluster of acute respiratory illness and higher interleukin 2 (IL-2), IL-7, IL-10, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF), interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP10), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1a (MIP1A), and tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-a) in plasma [1, 2]. It was caused by an unknown beta coronavirus, initially called as 2019-nCoV; later the unknown beta coronavirus was named SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), which formed a clade within the subgenus Sarbecovirus [2, 3]. Apart from the well-known MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus) and SARS-CoV (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus), the SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh member of the coronavirus family that infects humans [4]. The genome of SARS-CoV-2 has 89% and 82% nucleotide similarity with bat SARS-like-CoVZXC21 and of human SARS-CoV, respectively. The phylogenetic trees of spike, membrane, envelope, orf1a/b, and nucleoprotein from SARS-CoV-2 are clustered closely with those of the bat, civet, and human SARS-CoV. The external subdomain of the spike’s receptor of SARS-CoV-2 has 40% amino acid similarity with other SARS-related CoV [5]. The entire orf3b of SARS-CoV-2 encodes a novel short protein. Moreover, new orf8 of SARS-CoV-2 probably encodes a secreted protein with an a-helix, a b-sheet(s) having six strands [5]. The phylogenetic analysis of the complete viral genome (29,903 nucleotides) revealed that WH-Human-1 coronavirus (WHCV) or SARS-CoV-2 was most closely related (89.1% nucleotide similarity) to a group of SARS-like coronaviruses (genus Betacoronavirus, subgenus Sarbecovirus) that were previously sampled from bats in China and that have a history of genomic recombination [6]. A recent study confirmed that the SARS-CoV-2 uses the ACE2 cell entry receptor, similar to SARS-CoV [7].

Considering the outbreak and the high need for treatment strategies, we have carried out an in-silico approach to identify the best ligand against the SARS-CoV-2 envelope and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein.

Material and methods

Sequence retrieval and secondary structure prediction

The amino acid sequence of the Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus envelope protein (Accession no QHD43418.1), nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (Accession no QHD43423.2), were retrieved from the NCBI database on 28th Jan 2020. Wuhan seafood, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome and other sequences were retrieved from NCBI, and sequence alignment was done by MAFFT software [8] for both envelop and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein, and phylogeny was constructed using MEGA7 [9–11].

Homology modelling

The sequences of envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein were searched against the protein database using BLAST-P [12]. The proteins having PDB Id: 1ssk.1.A for nucleocapsid phosphoprotein [13] and 5x29.1.A for envelope protein [https://swissmodel.expasy.org/repository/uniprot/A3EX99] were selected for use as a template for 3D modelling of the envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoproteins of SARS-CoV-2. FASTA sequences were obtained for target and template selection.

3D structure prediction and validation

Homology modelling structure prediction was carried out using the Automated SWISS MODEL server [14]. The modelled PDB file was visualised using PyMOL and validated using PROCHECK [15]. 3D models were validated on the basis of Ramachandran plot [16] statistics using the RAMPAGE server as described earlier [17] and ERRAT2 [18]. From the generated models, the one with highest number of residues in the allowed region and minimum number of residues in the disallowed region were considered as a suitable model for envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 and then used for further analysis. The active site was predicted using the MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) tool site finder [19]. The two predicted models of 3D atomic coordinates of the receptor were used for computations to verify potential sites for ligand binding and docking.

Preparation of ligand for docking analysis

Chemical compounds were taken from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Pub-Chem database. All the ligands involved in our report were accumulated from the ones available in the literature [20–23], and others are listed in Table I. The ligands for envelop protein (1I75, 2CBU, 2AAC, 1JR1) and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (4UCE, 4UCC, 4UCD, 4UC8) were downloaded from a protein databank in Structure Data File (SDF) format and later converted to Protein Data Bank (PDB) coordinate files using Marvin space software, and ligands were saved in .mol format with the aim of opening these files in MOE software. Energy minimisation was done using MOE tools to first protonate the structure by using default parameters pH 7 and temp 300˚C. The selected ligand molecules were passed through a Lipinski filter.

Table I

The properties of the ligands in the active site of envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of Wuhan coronavirus, 2019-nCoV

| Protein | Ligand | Number of bonds | HbA | HbD | Log P | DG [kcal/mol] | pKi [µM] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Envelope | E1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | –2.194 | –7.1939 | 5.509 |

| E2 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3.00* | –10.2567 | 7.713 | |

| E3 | 6 | 4 | 5 | –3.899 | –7.9052 | 8.105 | |

| E4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | –3993 | –6.7359 | 8.761 | |

| Nucleocapsid phosphoprotein | N1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1.733 | –10.3805 | 7.067 |

| N2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2.901* | –12.2112 | 7.885 | |

| N3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2.248 | –9.3889 | 7.284 | |

| N4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | –1.411 | –8.6312 | 5.725 |

* Significant druggable protein ligand; HbA – hydrogen bond acceptors, HbD – hydrogen bond donors, log P – The log octanol/water partition coefficient, pKi – estimated binding affinity, E1 – b-D fucose, E2 – mycophenolic acid, E3 – castanospermine, E4 – deoxynojirimycinIs, N1 – M72: 1-[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid, N2 – M76: 1-[(2,4-dichlorophenyl)methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid, N3 – M81: 1-[(2-chlorophenyl)methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid, N4 – P1: phenylalanine.

Molecular docking

For molecular docking the two modelled structures of selected antiviral molecules with envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein were 3D protonated, and then docking was performed; we selected ligand (b-D-fucose; mycophenolic acid; castanospermine; deoxynojirimycin; 1-[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid; 1-[(2,4-dichlorophenyl)methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid; 1-[(2 chlorophenyl) methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid, and the PHENYLALANINE atom. Settings were selected in MOE software as rescoring1 at London dG and rescoring2 at GBVI/WSA dG, and the ligand interaction was performed with protein [24]. Four ligands were used for envelope protein, and another four ligands were used for nucleocapsid phosphoprotein. Energy minimisation was done for both ligands and proteins. Envelope protein before energy minimisation E: 5471.98, RMS: 14.93, and after energy minimisation E: 2433.49, RMS: G = 0.0709512, E: 2489.62, RMS G = 0.0700238, E: 2477.92, RMS: G = 0.0713067, and E: 2562.35, RMS: G = 0.124056 with b-D-fucose, mycophenolic acid, castanospermine, and deoxynojirimycinIs ligands, respectively. For nucleocapsid phosphoprotein before energy minimisation: E: 2673.4, RMS: G = 17.3825, and after energy minimisation E:475.537, RMS G = 0.0875944, E:428.511, RMS G = 0.0805305, E: 372.844, RMS G = 0.0508421, and E: 390.26, RMS G = 0.0939766 with M72, M76, M81, and P1 ligands, respectively.

Results

The amino acid sequences of envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein were blasted against the PDB-BLAST database to identify an appropriate template for homology modelling. The protein having PDB Id: 1ssk.1.A (seq. identity 92.37, seq. similarity 0.61) and 5x29.1.A (seq. identity 91.38, seq. similarity 0.54) were selected as a template for 3D modelling of the envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein. The SWISS MODEL server was used to predict the 3D structure of the envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein. Models were built based on target-template alignment using ProMod3 in the SWISS MODEL server. The best models of envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein were selected based on the best QMEAN score (0.01) and highest resolution 2.48Å, and were validated using the RAMPAGE sever.

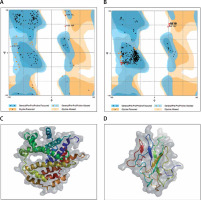

The protein structure’s stereochemical stability was calculated with the help of a Ramachandran plot. The Ramachandran plot explained the 3D structure of the envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein, showing 84% and 90.4% amino acid residue of predicted structure are in the favoured region for the nucleocapsid phosphoprotein and envelope protein, respectively. Also, amino acid residues in the allowed region were 6.1% (nucleocapsid phosphoprotein) and 13.3% (envelope protein), and the remaining number of residues in the outlier region was 3.6% (nucleocapsid phosphoprotein; Figure 1 B) and 2.2% (envelope protein; Figure 1 B). The overall quality factors for nucleocapsid phosphoprotein and envelope protein of the predicted models at ERRAT2 were 94 and 87, respectively.

Figure 1

A, B – Ramachandran plot from RAMPAGE of Wuhan coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 protein. A – Envelope protein; B – Nucleocapsid phosphoprotein. The phi (φ) values of amino acid residues are on the x-axis. The psi (ψ) values are on the y-axis. C, D – 3D structure of envelope protein (C) and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (D) after homology modelling

Molecular docking

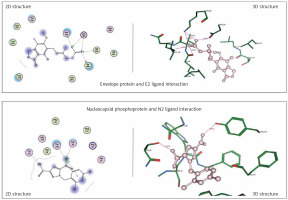

Envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 were prepared for molecular docking and were analysed by MOE software initially by 3D protonation, energy minimisation, and prediction of active site for the eight ligands by keeping the parameters at their defaults. Then the ligands (E1 to E4 and N1 to N4) were docked separately with the envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 2, 3) using MOE software. The results from molecular docking suggested that the E2: mycophenolic acid (log P = 3.00; DG = –10.2567 kcal/mol; pKi = 7.713 µM) was the most potent druggable protein ligand of the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein (Figures 2 A, B), while N2, 1-[(2,4-dichlorophenyl)methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid (Log P = 2.901; DG = –12.2112 kcal/mol; pKi = 7.885 µM) was the most potent druggable protein ligand of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein protein (Table I, Figure 2).

Figure 2

Significant druggable protein ligand complex of envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. E2 ligand has five hydrogen bonds: one with Asn_64, two with lys_63, one with val_49, and one with ILE_46. N2 has two hydrogen bonds: one with Thr 49, and the other with Tyr112, in addition to one arene-arene interaction with Tyr 109

Discussion

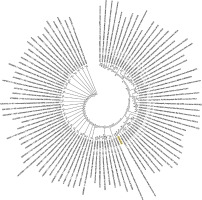

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a global pandemic health threat. SARS-CoV-2 was identified as a new strain of the Beta-CoVs genera, and is a member of the zoonotic origin coronavirus group. It causes coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), which is the greatest concern in all the countries involved in the outbreak for health and economy reasons. SARS-CoV-2 is distinct from the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus [2, 3, 25–27]. However, the phylogenetic analysis of the envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein revealed that these proteins are close to the nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of bat coronavirus and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (Figures 4–6). Hence, the study was designed to predict potent ligands against druggable envelope and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. The 3D models of the envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 were predicted, validated, and used for docking studies. The docking studies help in the prediction of the preferred orientation of a ligand with the binding site on a protein and are used for conformation of various chemical compounds at the target site of the protein. The most potent identified compounds for envelope protein, mycophenolic acid and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein, 1-[(2,4-dichloro-phenyl)methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid) with highest log octanol/water partition coefficient (Log P), high number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, lowest non-bonded interaction energy (DG) between the receptor and the ligand, and high binding affinity (pKi), indicate that they are the most potent compounds against the SARS-CoV-2 envelope and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein.

Figure 4

Phylogenetic analysis of the nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 by Maximum Likelihood method. “The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model [11]. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 500 replicates [10] is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analysed [10]. Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying neighbour-joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a JTT model, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The analysis involved 78 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 43 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 [9].” Nucleocapsid phosphoprotein sequence used for constructing the phylogenetic tree: MSDNGPQNQRNAPRITFGGPSDSTGSNQNGERSGARSKQRRPQGLPNNTASWFTALTQHGKEDLKFPRGQGVPINTNSSPDDQIGYYRRATRRIRGGDGKMKDLSPRWYFYYLGTGPEAGLPYGANDGIIWVATEGALNTPKDHIGTRNPANNAAIVLQLPQGTTLPKGFYAEGSRGGSQASSRSSSRSRNSSRNSTPGSSRGTSPARMAGNGGDAALALLLLDRLNQLESKMSGKGQQQQGQTVTKKSAAASKKPRQKRTATKAYNVTQAFGRRGPEQTQGNFGDQELIRQGTDYKHWPQIAQFAPSASAFFGMSRIGMEVTPSGTWLTYTGAIKLDDKDPNFKDQVILLNKHIDAYKTFPPTEPKKDKKKKADETALPQRQKKQQTVTLLPAADLDDFSKQLQQSMSSADSTQA

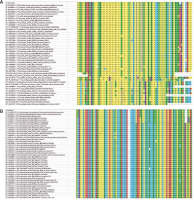

Figure 5

Representative of the multiple protein sequence alignment of envelope protein (A) and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (B) of Wuhan novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. Envelope protein and nucleocapsid phosphoprotein sequence used for the sequence alignment are available in Figures 4 and 6, respectively

Figure 6

Phylogenetic analysis of the envelope protein of Wuhan coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 by Maximum Likelihood method. “The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model [11]. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 500 replicates [10] is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analysed [10]. Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying neighbour-joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a JTT model, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The analysis involved 78 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 43 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 [9].” Envelope protein sequence used for constructing the phylogenetic tree: MYSFVSEETGTLIVNSVLLFLAFVVFLLVTLAILTALRLCAYCCNIVNVSLVKPSFYVYSRVKNLNSSRVPDLLV

The coronavirus nucleocapsid phosphoprotein is a multifunctional structural protein; during virion assembly it interacts with the viral membrane and forms complexes with genomic RNA. The coronavirus nucleocapsid phosphoprotein plays an important role in coronavirus transcription and assembly as well as the coronavirus lifecycle [28–34]. The most potent identified compound, 1-[(2,4-dichlorophenyl)methyl]pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid], may inhibit any of its multifarious activities and functions during virion assembly; however, detailed studies are needed on the inhibitory effect of these compounds on the interaction of nucleocapsid phosphoprotein with the viral membrane, and formation of complexes with genomic RNA during SARS-CoV-2 transcription and virion assembly.

The coronavirus envelope protein plays a crucial role for the lifecycle of the virus. The small integral membrane protein, the coronavirus envelope protein, is important for the development of the disease in the host through viral assembly, to exit the host cell by viral budding, viral propagation, envelope formation by taking portions of the host cell membranes, and the release of infectious virus from the host cell [33–35]. Hence, the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein was considered for the docking study to identify the most potent compound; the study revealed that mycophenolic acid may an appropriate druggable protein ligand of SARS-CoV-2 to inhibit the development of a COVID-19 by blocking the viral assembly. Complete wet lab analysis is needed to elucidate the impact of the mycophenolic acid on the virus’ exit from the host cell by viral budding, the effect on blocking the envelope formation by taking portions of the host cell membranes, as well as its controlling power on release of infectious virus from the host cell.

There is no defined curative treatment for COVID-19 or any approved vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection. The WHO recommendation for the management of MERS-CoV is being in practice: initiation of oxygen therapy to keep the oxygen saturation above 90%, with conservative fluid management in the absence of shock, and an empiric antimicrobial regimen that includes antibiotics and a neuraminidase inhibitor for treatment of influenza. All of those supportive treatments are for the prevention of acute respiratory distress syndrome and for the prevention septic shock [2, 3, 36]. Hence, drug development against SARS-CoV-2 is considered urgent in order to fight COVID-19. The present in-silico approach identifies one potent ligand against the envelope protein and one potent ligand against nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. A combination of these two ligands might be the best option to consider for further detailed studies in wet laboratories to develop a drug for treating patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.