Introduction

Encephalopathy and stroke in COVID-19 patients have been repeatedly reported [1–5]. Previous reports indicate that SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with a significantly escalated risk of ischaemic stroke, especially with potential cryptogenic stroke. The incidence of ischaemic stroke in the context of COVID-19, according to various reports, varies between 2.5% and 6.4%, but may be higher [1]. Instances of strokes comorbid with COVID-19 are characterised by the patients’ lower than average age, large vessel occlusion, possible antiphospholipid antibody production, raised inflammatory markers, concomitant venous thromboembolism and multi-territory infarcts. Additionally, preceding vascular comorbidities are frequently observed, and the incidence of stroke increases with COVID-19 severity [4, 6–8].

Encephalopathy is also present in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). CADASIL is the most common monogenic vascular disease which causes young-adult onset of cerebrovascular disease. The definitive diagnosis of CADASIL is based on sequencing the NOTCH3 gene, as it results from pathogenic, loss-of-function mutations in this specific gene [9, 10]. The primary pathology is the accumulation of abnormal transmembrane deposits on vascular smooth muscle cells in the brain and other organs [11]. This leads to impaired vascular function, resulting in recurrent ischaemic incidents that manifest with migraine with aura, transient ischaemic attacks or strokes and dementia before the age of 60 [12]. CADASIL has a gradual and progressive course in younger patients, who are often free from classical vascular risk factors.

Hereby we present a case of a 30-year-old patient with COVID-19 and mild systemic biochemical signs of inflammation associated with leukoencephalopathy, which was finally diagnosed as CADASIL.

Case report – COVID-19 patient

A 30-year-old woman with a history of allergic reaction, spastic right sided hemiparesis and paresis of the right abduction nerve (neurologic deficit present from the age of two, never radiologically diagnosed) was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection with reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of nasopharyngeal swab. The patient was free of vascular risk factors.

The onset of the infection started with temperature elevated to 37°C. Three days after the initial symptoms the patient complained of a swollen tongue, anosmia and general weakness. On the 11th day of the illness the patient was admitted to an emergency department with right-sided pulsating headache, dysarthria, fatigue and psychomotor slowness. The patient’s general condition was good, and oxygen saturation and blood pressure were normal. Leucocytosis grew to 15.7 thousand/μl. The remaining biochemical tests and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were normal. Microbiological tests ruled out the presence of bacteria in urine, faeces and blood.

Chest CT revealed small peripheral areas of ground glass opacities in the lower segments of both lungs (3.16% lung surface occupancy).

Intravenous treatment with ceftriaxone and acyclovir was commenced, regardless of which on the 3rd day of treatment the patient’s consciousness deteriorated and neck stiffness occurred. CSF for JC virus and SARS-CoV-2 virus was negative. CSF was also negative for bacteria. The levels of class G immunoglobulins were elevated and measured at three times higher than regular values. No oligoclonal bands were present. Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza viruses in serum was ruled out.

The patient had been administered intravenous immunoglobulins, 30 g/day, for 3 days. During the following days impaired consciousness and dysarthria deepened, and neck stiffness was still present. Convalescent plasma was given on the 20th and 21st day (1 unit per day) when the first neurological symptoms occurred. Blood samples were collected before and after plasma administration in order to assess the inflammatory parameters. After convalescent plasma transfusion increases in IL-2, IL-8 and TNF-α were observed whereas IL-15 was decreased (Table I). Moreover, the concentrations of other cytokines (IL-1a, IL-1b, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, IL-23, INF-γ, TNF-β) did not change.

Table I

Levels of cytokine and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase before and after plasma transfusion of convalescents (pg/ml)

| Parameter | IL-2 | IL-8 | IL-15 | TNF-α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels before | 30.60 | 22.94 | 28.10 | < 17.28 |

| Levels after | 40.19 | 38.58 | < 26.88 | 39.09 |

After transfusion of convalescent plasma, the patient’s neurological condition improved [13]. Within 12 days of admission to the hospital clinical symptoms subsided. Follow-up CT of the lungs revealed no pathology. Anosmia disappeared, and speech returned to normal. Slowness, general weakness and sleepiness also ceased.

At discharge and during follow-up visits (1 to 6 months after hospitalization) on neuropsychologic examination, discrete weakening of the concentration, attention, direct memory and executive functions was still present. There was no cognitive dysfunction, but the tendency of reduced mood was observed. The patient reported depression, general weakness, fatigue and right-sided migraine-like headaches, which gradually disappeared.

The process leading to CADASIL diagnosis

Neuro-radiologic data

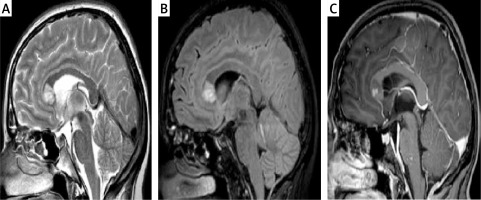

The first MRI scans of the brain were performed on the 12th day of the infection and as soon as neurological symptoms began. They revealed the presence of multiple, at least a dozen, hyperintense foci in T2 WI and FLAIR, which were located in the white matter of both hemispheres (frontal, parietal and temporal lobes were affected), with the most prominent lesions situated symmetrically close to the lateral ventricles, and a single one in the knee of the corpus callosum. Some of the foci presented nodular contrast enhancement and diffusion restriction on DWI 9 (Figures 1, 2). There were no infratentorial lesions. MRI of the cervical spine was normal. Apart from these lesions, a small subdural haematoma of the right hemisphere was present, but there were no intraparenchymal microhaemorrhages. Meningeal thickening and contrast enhancement of the right hemisphere were present.

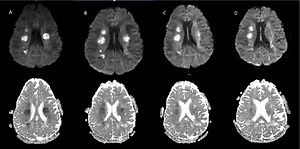

Figure 1

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain on admission 5/08 (A) and the dynamics of changes in the control examinations 8/08 (B), 13/08 (C), 20/08 (D)

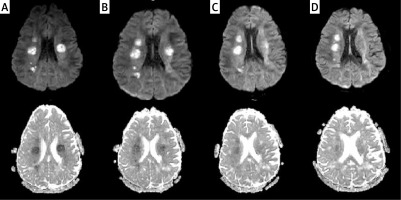

Figure 2

FLAIR image (A) shows confluent hyperintensities within the white matter of the anterior temporal poles. FLAIR image at the level of lateral ventricles (B) demonstrates white matter changes within the external capsules (mainly on the right)

Subsequent control MRI scans of the brain (13.08, 20.08.2020) showed white matter changes within the cerebral hemispheres without significant dynamics, i.e., the location and morphology. The sizes of the lesions were of similar volume with slight contrast enhancement (Figure 2).

The follow-up MRI examination (3.09.2020) revealed the lesions which showed slight diffusion restriction on DWI and discrete contrast enhancement. Meningeal thickness was no longer present.

The last follow-up examination (05.11.2020) showed the same number of lesions, showing no diffusion restriction on DWI or enhancement after gadolinium-based contrast administration.

Genetic data – whole genome sequencing

Considering the fact that in March 2020 the hospital was transformed into a unit handling solely COVID-19 patients, the opportunity arose to participate in projects related to broadening the knowledge about the disease and improving the care patients can receive. One of those ongoing projects focuses on genetic factors contributing to the severity of COVID-19 and potential immunity. The patient agreed to participate in the study and therefore whole genome sequencing (WGS) was applied, which allowed identification of the genetic background of neurological symptoms.

The patient’s genome was sequenced with the average depth of coverage 32.7× and mapped to the reference genome GRCh38. The WGS approach identified heterozygous missense variant NOTCH3(NM_000435.3):c.1320C>G p.(Cys440Trp) in exon 8 (NC_000019.10:g.15189047G>C). Targeted Sanger sequencing was done to confirm the presence of the variant; it was also performed on the patient’s closest relatives – both parents and siblings (brother and sister) (Figure 3). Beside the patient, all family members were unaffected; the variant appeared de novo.

Figure 3

Pedigree of the patient’s family. Affected individuals marked in red. The patient was analysed using the WGS approach and following targeted Sanger sequencing validation. All other family members were tested only with targeted Sanger sequencing. Corresponding electropherograms are located below each family member representation

The identified variant was not reported in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD v.3), 1000 Genomes, or in the polymorphism database dbSNP. No clinical information was available in ClinVar. The only information regarding variants in the same amino acid position (Cs440Ser and Cys440Gly) from the LOVD database were reported by Markus [14]. They were found in 2 individuals affected with CADASIL and interpreted as pathogenic on the basis of symptoms and familial cosegregation.

The variant is located in the hot-spot region related to pathogenic mutations (all other known non-VUS missense/in-frame variants in this 51-nt long region were pathogenic). The identified variant was also evaluated to be deleterious/pathogenic by 11/12 online in silico prediction tools (based on pathogenic predictions from BayesDel_addAF, DEOGEN2, EIGEN, FATHMM-MKL, LIST-S2, M-CAP, MVP, MutationAssessor, MutationTaster, REVEL and SIFT vs only one benign prediction from PrimateAI) [15–26]. Pathogenicity was confirmed using ACMG/AMP guidelines (PS2, PM1, PM2, PM5, PP2, PP3, PP4) [27]. The identified variant in the NOTCH3 gene allowed us to make the diagnosis of CADASIL.

In addition to the NOTCH3 finding we registered a 4-fold lower level of blood mitochondrial DNA in the patient than the average of the Polish population (lower than the 3rd percentile). While the average blood mtDNA in our 890 healthy donor group was 79 copies per cell, the patient displayed only 20 genomes per diploid cell.

Although ADEM is thought to be a post-infectious disorder, the aetiology is still poorly understood. There was a single report on a mitochondrial genetic factor that could be the cause of ADEM in a paediatric patient. POLG – the nuclear gene coding a mitochondrial protein – was hypothesized to be causative or at least contribute to the disease [28].

The adult patient described in our report was not diagnosed with mitochondrial depletion syndrome as she displayed no clinical symptoms, apart from childhood-onset hemiparesis of unknown aetiology. As most congenital neurological syndromes that could have mimicked ADEM occur in children, we find it unlikely that such an encephalomyelitis type developed in an adult.

Nonetheless, we cannot exclude that a very mild mitochondrial depletion as well as NOTCH3 variant could have contributed to ADEM, which was triggered mainly by viral infection.

Methods and materials of whole genome sequencing

The integrity of the proband’s isolated DNA was verified in 1% agarose gel. A library of 550 bp DNA fragments was prepared using the TruSeq DNA PCR Free kit (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) and the quality of this library was examined using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Next, 2 x 150 bp paired-end WGS was performed by Macrogen (Amsterdam, Netherlands), on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, yielding > 30× mean depth of coverage.

Data quality was assessed using FastQC v0.11.7 [14]. Reads were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome using the Speedseq v0.1.2 toolkit [29] (BWA MEM 0.7.10 [30] alignment, Sambamba v0.5.9 [31] deduplication), and SNVs and indels identified by DeepVariant 0.8.0 software [32]. Copy number variants were called using CNVnator v0.4 [33]. All variants were annotated using Variant Effect Predictor [34], and analysis constrained to variants in a predefined set of 885 genes associated with neurological diseases (list available in supplementary material). SNVs with population frequency above 1% in the gnomAD population were excluded from the analysis. Resources used when assessing pathogenicity of candidate variants included: gnomAD v2.1.1 [35], dbSNP (153) [36], ClinVar [37], the Human Gene Mutation Database v2019.1 [38], OMIM [39], UniProt [40], KEGG v91.0 [41], and pathogenicity prediction scores such as SIFT [42], PolyPhen-2 [43] and CADD [44]. Targeted Sanger sequencing was performed on DNA samples of all family members subjected to genetic testing to confirm WGS results.

Results

Pathogenic variants in the NOTCH3 gene were described as related to cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) – the most common inherited stroke disorder [45]. The clinical spectrum of the disease includes recurrent ischaemic episodes, progressive cognitive deficits, migraine and psychiatric disorders.

The NOTCH3 gene encodes a single-pass transmembrane receptor containing 34 epidermal growth factor repeats (EGFr). Each EGFr is composed of approximately 40 amino acids, all containing 6 cysteine amino acids that form disulfide bridges [46]. NOTCH3 mutations in CADASIL invariably lead to an uneven number of cysteines and disrupt normal disulfide bridge formation, causing misfolding of EGFr and increased NOTCH3 multimerization [47]. This NOTCH3 aggregation has a toxic effect on vascular smooth muscle cells. These changes lead to impaired cerebrovascular reactivity and decreased cerebral blood flow, believed to cause both chronic cerebral ischaemia and acute ischaemic events [48, 49]. Acute infection in the course of COVID-19 may stimulate inflammatory reactions, hypoxia and coagulopathy, which can additionally trigger ischaemic infarctions even in patients without classic vascular risk factors. A few patients with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and CADASIL, who presented with multiple ischaemic infarcts, have recently been reported [50–52].

The identified variant p.(Cys440Trp) is located in EGFr 11, which has been related to a much milder phenotype and neurological symptoms occurring 12 years later than those with pathogenic variants located in EGFr [53].

Another interesting finding in our patient is the strikingly low level of mitochondrial DNA in the blood, below the 3rd percentile in the distribution of our reference healthy donor group. Several studies have shown the correlation between mtDNA blood levels and general fitness, risk of cardiovascular diseases and neurological functioning, especially in the elderly [54–56]. The low copy number of mtDNA in our proband could have been involved in the patient’s condition, acting as a genetic modifier of the underlying condition. This finding may be at least partially responsible for the relatively early age of CADASIL onset and clinical display in the presented patient.

The simultaneous COVID-19 infection could probably provoke an exacerbation of a previously asymptomatic CADASIL patient and could lead to acute ischaemic multi-infarct encephalopathy, as the association between CADASIL and SARS-CoV-2 infection as a trigger mechanism has been described [50, 51, 57, 58]. There is also an association between CADASIL and influenza A infection. The infection can cause the appearance of new neurological symptoms [59]. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that worsening of neurological symptoms can appear when treating migraine in CADASIL patients with anti-migraine drugs (e.g. drugs blocking CGRP), but this needs further investigation [60]. There are rare descriptions of the coexistence of autoimmunity in CADASIL patients which may possibly worsen clinical symptoms and signs [61].

Our patient developed symptoms of encephalopathy prior to clinical and radiological pulmonary symptoms. Moreover, the pulmonary symptoms during hospitalization were mild. The patient had radiologic features of pneumonia, which did not require any treatment other than high-flow oxygen therapy 20 l/min. The levels of IL-6 and other inflammatory markers outside the CNS were relatively low. The patient was initially treated with iv immunoglobulins, as the differential diagnosis included ADEM.

Many inflammatory and noninflammatory disorders can have similar clinical and radiologic features and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Bacterial and viral inflammatory process were excluded (cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, the level of cerebrospinal fluid proteins and immunoglobulin index, gadolinium enhancement in MRI). Anti-MOG associated encephalomyelitis was also within the differential diagnosis. It was excluded due to the absence of anti-MOG antibodies. ADEM was suspected on the basis of clinical features and neuroimaging results. Magnetic resonance abnormalities in ADEM are frequently present in T2 weighted and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences as non-uniform, poorly marginalized areas of increased signal intensity. They are usually large, multiple and asymmetric, and occur in subcortical and cortical areas. Periventricular white matter is also often involved. This correlated well with the radiological picture in our patient.

Thereafter the patient was administered convalescent plasma. Convalescent plasma, due to the high titre of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies, is effectively used in the prevention and treatment of epidemic infections. These antibodies prevent the virus from entering the human cell by attacking one of the functional subunits of the S-glycoprotein, and therefore play a key role in direct virus neutralization. In the study by Tworek et al., unlike in many other publications, shortened hospitalization was not observed in COVID-19 patients [13]. On the other hand, it was found that sufficiently early administered convalescent plasma may significantly reduce the development of acute respiratory failure and the need for mechanical ventilation.

Referring to the above, we suggest that the speed of disease progression, neurological deficits correlating with numerous diffuse changes in the brain imaging and the coexistence of preceding SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to a hypothesis that this infection was responsible for the development of encephalopathy, with predominant white matter changes.

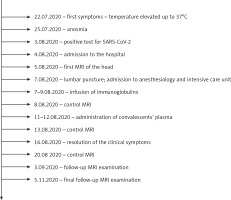

To improve the clarity of the results, a timeline of patient management (Figure 4) and a list of genes in the neurological panel (Table II) are presented.

Table II

List of genes in the neurological panel

Discussion

The diagnosis of white matter changes requires a broad approach combining sequential neuroimaging, clinical features, the course of the disease and laboratory data. White matter diseases affect the pattern of myelination and include a large diversity of acquired processes, e.g., autoimmune, infectious, vascular. These processes could play a role in the present case.

In our CADASIL patient, the restriction of diffusion of the lesions and its slow normalization over time could also suggest subcortical lacunar infarcts (Figure 1). However, this radiologic feature may also be present in ADEM associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Differential diagnosis between the two – ADEM and CADASIL – may be a great challenge [50], as it was in the present case.

One of the essential features of the white matter lesions’ radiological assessment is the analysis of their distribution and evolution over time. Some studies have suggested that both anterior temporal lobe involvement and external capsule involvement are characteristic markers that may differentiate CADASIL from other diseases [62–64].

Furthermore, the blood vessels of CADASIL patients are directly exposed to a variety of endogenous or exogenous inflammatory stimuli. Ling et al. analysed the expression levels of cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) and vascular endothelial cells (VEC) and TNF-α-induced inflammation was increased in both CADASIL VSMC and VEC. The ELISA assay further confirmed the upregulation of IL-6 protein in CADASIL VSMC and VEC culture medium in TNF-α-induced inflammation. In addition, they found increased adhesion of monocytes to CADASIL VEC in TNF-α-induced inflammation. Together, CADASIL VSMC and VEC showed higher sensitivity to inflammatory stimuli [26].

In addition, cytokine release in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection may lead to mild to severe clinical symptoms. Patients with severe conditions showed serum profiles with dramatically increased plasma levels of interleukins up to the state of “cytokine storm”, including IL-6, IL-2, IL-7 and IL-10 [65]. In severely ill SARS patients, the concentrations of IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, TGF-β, MCP-1 and IL-8 were higher than in patients with mild to moderate symptoms [66, 67]. Historically, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 levels were also increased in patients with severe MERS-CoV infection [68].

With regard to the decreased level of IL-15, it is a critical immunoregulatory cytokine with antiviral properties [69]. IL-15 is expressed by bone marrow cells to help with T cell responses, activate NK cells, and modulate inflammation [70]. Deficiency of IL-15 has previously been shown to promote airway resistance in mice, while IL-15 inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines, reduces goblet cell hyperplasia and regulates allergen-induced airway obstruction in mice by inducing interferon (IFN-γ) and IL-10-producing regulatory T cells [71].

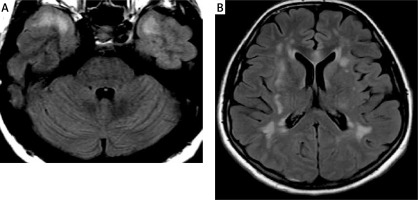

In the present case, there were confluent white matter changes in the anterior temporal lobes and in the area of both external capsules (Figure 2). Similar localization of the lesions was described in another case recently reported by Zhang [49]. Some authors also emphasize the frequent location of the radiological changes in the upper frontal gyri, which is not present in our patient [64]. Other locations in which changes in the course of CADASIL syndrome may occur include the posterior temporal and occipital white matter, the basal ganglia, thalamus, internal capsule and the pons [64]. The involvement of the corpus callosum is a typical multiple sclerosis (MS) feature, could be present in ADEM and affects about 40% of patients with CADASIL [72]. The involvement of the corpus callosum is present in our case (Figure 5), but it was absent in the report of Zhang. In contrast, the occurrence of lesions in all infratentorial regions except the pons is unusual [49, 64, 72].

Figure 5

The lesion in the genu of the corpus callosum shows high signal intensity on T2 WI (A) and FLAIR (B) and punctate enhancement after intravenous contrast administration (C)

It has been suggested that white matter changes in ADEM should regress over time [73], while in our case the changes are still significant after 7 months of observation.

Although absent in our case, microbleeds may occur in 30–70% of CADASIL patients, and their frequency of occurrence increases with patient’s age; intracerebral haemorrhage have also been described in a number of patients [5, 74, 75]. Our patient was only 30 years old and did not have any vascular risk factors.

Contrast enhancement present in the acute phase of the disease does not significantly narrow the differential diagnosis and may occur in many white matter diseases [72].

Subcortical lacunar infarcts on a background of chronic microangiopathic ischaemic changes, and white matter of the anterior temporal poles, superior frontal lobes, and external capsules are typically affected. These are the key diagnostic features of CADASIL, present in our patient.

In spite of de novo origin of the identified NOTCH3 variant in the patient, the patient’s mother suffered an early stroke episode at the age of 46. The event was not related to COVID-19 and she had no other predisposing conditions. The phenocopy could be uncorrelated to the proband’s CADASIL; other unknown, potentially female-specific, genetic factors could cause neurological conditions; or there could be an obscured mosaicism in the mother. Notably, Markus et al. reported that 19.5% of tested individuals, in whose families CADASIL occurred, suffered an ischaemic stroke but did not harbour the pathogenic mutations [14].

Recently, it has been shown that CADASIL pathogenic variants may occur in 1 : 300 individuals in the general population [49]. This frequency is higher than the minimal estimated CADASIL prevalence, which means that CADASIL may be underdiagnosed. It could be suggested that a number of pathogenic mutations in the population are associated with milder phenotype or are non-penetrant. The awareness of a potentially high number of asymptomatic CADASIL individuals in the population may have important implications for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with neurological symptoms related to COVID-19 and other acute infections. Determining the process which causes ischaemic infarcts in CADASIL patients with COVID-19 could enable appropriate measures of prevention to be applied in the foreseeable future.

In conclusion, this case underlines diagnostic difficulties associated with making the proper diagnosis as the clinical features and radiologic findings may be similar in a number of different entities. The proper diagnosis is of paramount importance as it can lead to applying successful treatment. The diagnostic process undertaken in this study strongly supports the value of widespread use of WGS, as it can contribute in future to lowering the number of undiagnosed CADASIL patients and therefore resolve the problem of underdiagnosing CADASIL in the general population. The same could be said about other underdiagnosed health conditions with underlying genetic factors, which were not a part of this study.