Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is an autosomal co-dominant inherited disorder of lipoprotein metabolism characterized by markedly elevated plasma LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration from birth [1]. Therefore, patients with FH have an increased risk of premature development of atherosclerosis, particularly atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD) and/or coronary artery disease (CAD) [2]. Although heterozygous FH (HeFH) is one of the most common genetic disorders, and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, it is very often underdiagnosed and massively undertreated [3–6]. Therefore, recently registries of FH are being developed to assess gaps in care and improve disease management and outcomes [7] and attempts are in progress to identify secondary treatment targets other than LDL-C – which is the most important and primary target – to reduce the risk of ACVD in these patients [8–11]. The prevalence of FH in the general population is estimated at around 1 in 200–500, while there are data indicating that in patients with established CAD, the prevalence of potential FH seems to be even 8.3%; 7.5% in men and 11.1% in women [12]. FH is, in more than 90% of cases, caused by loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in the gene encoding LDL receptor (LDLR), which have as a consequence a decreased cellular uptake of LDL particles and therefore significantly elevated plasma LDL-C concentrations [13]. Currently more than 1700 such mutations have been documented [14, 15]. However, mutations of other genes related to apolipoprotein B that affect the LDLR-binding domain of apolipoprotein B as the most important apolipoprotein for LDL particles’ uptake, and the gain-of-function (GOF) mutations of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin9 (PCSK9) – a serine protease essential for LDLR recycling – have also been identified and they result in an identical phenotype as patients with LDLR mutations [2, 16].

Atherosclerosis of the arteries causes loss of elasticity and increased rigidity, resulting in increased velocity of pulse waves since they travel faster in stiff arteries. Arterial stiffness is a robust predictor of all-cause and CVD mortality, fatal and non-fatal coronary events and fatal strokes [17–20]. As pulse wave velocity (PWV) is the most widely used and validated technique for estimating arterial stiffness, high PWV represents an early sign of arteriosclerosis/atherosclerosis [21].

Intima-media thickness (IMT), particularly carotid IMT, is recognized as a surrogate marker of atherosclerosis, given its predictive association with CAD [22]. Therefore, it was considered that the measurement of carotid IMT and/or screening for atherosclerotic plaques by carotid artery ultrasound can add information beyond assessment of traditional risk factors in asymptomatic adults at moderate CV risk [23]. However, the evidence that measurement of common carotid IMT can improve the risk prediction of CVD events is inconsistent [24]. Even the position paper from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripheral circulation stated that it is still unclear whether a specific vascular biomarker (including IMT) is clearly superior and that a prospective study in which all vascular biomarkers are measured is still lacking [25].

The aim of this meta-analysis was to establish whether PWV as a marker of arterial stiffness is changed in patients with FH compared with non-FH individuals. The secondary goal of this meta-analysis was to determine whether IMT is different in FH patients compared with non-FH subjects.

Material and methods

Search strategy

The study was designed according to the guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, the PRISMA statement [26]. SCOPUS, PubMed-Medline, Google Scholar and ISI Web of Science databases were searched using the following search terms in titles and abstracts: (“familial hypercholesterolemia” OR “familial hypercholesterolaemia” OR “familial hypercholesterolemic” OR “familial hypercholesterolaemic”) AND (“pulse wave velocity” OR PWV OR aPWV OR cPWV OR fPWV OR cfPWV OR “arterial distensibility” OR “vascular distensibility” OR “aortic distensibility” OR “arterial stiffness” OR “arterial stiffening” OR “vascular stiffness” OR “vascular stiffening” OR “aortic stiffness” OR “aortic stiffening” OR “arterial compliance” OR “vascular compliance” OR “aortic compliance”). The wild-card term “*” was used to increase the sensitivity of the search strategy. No language restriction was used in the literature search. The literature was searched from inception to November 26, 2017.

Study selection

Original studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) an observational study (i.e., a case-control, cross-sectional or cohort design), (ii) comparison of vascular PWV between patients with FH and controls without FH, and (iii) presentation of information on PWV in each group. Studies with undefined control groups, duplicate or overlapped populations with a previous study, or reported PWV values in a single group were excluded.

Data extraction

The following data were basically needed: 1) first author’s name, 2) year of publication, 3) study location, 4) age and gender of patients, 5) number of patients (by gender if described), 6) study design, 7) type of FH (homozygous or heterozygous), 8) diagnostic criteria to define FH, 9) IMT values, 10) type of vessel on which PWV was measured, and 11) PWV values.

Quality assessment

Methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [27]. In this scale, three aspects of each eligible study are evaluated: (i) the selection of the studied patients (4 items), (ii) the comparability of the studied populations (one item) and (iii) the ascertainment of the exposure (3 items) in case-control studies or outcome of interest in cohort studies. A study can be awarded a maximum of one point for each item in the selection and exposure categories, whilst the comparability item can receive a maximum of two points.

Quantitative data synthesis

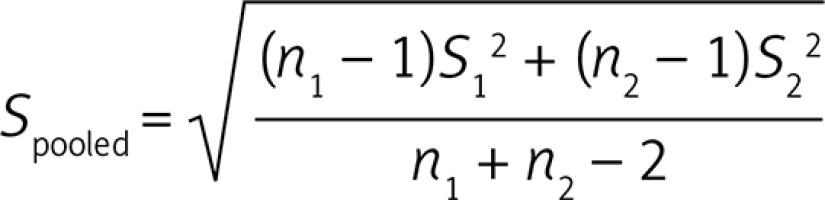

A meta-analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) V2 software [28]. All PWV values were collated in m/s. Standard deviation (SD) of the mean difference was calculated using the following formula:

Where n1 and n2 are population sizes of FH and control groups while S1 and S2 represent SD values of the respective groups.

If the outcome measures were reported in median and inter-quartile range, mean and SD values were estimated using the method as described by Wan et al. [29]. Where standard error of the mean (SEM) was only reported, SD was estimated using the following formula: SD = SEM × sqrt (n), where n is the number of subjects.

A random-effects model (using the DerSimonian-Laird method) and the generic inverse variance method were used to compensate for the heterogeneity of studies in terms of demographic characteristics of studied populations and also differences in the study design. Heterogeneity was quantitatively assessed using the I2 index. Effect sizes were expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). In order to evaluate the influence of each study on the overall effect size, sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave-one-out method, i.e. removing one study each time and repeating the analysis [30–32].

Publication bias

Potential publication bias was explored using visual inspection of Begg’s funnel plot asymmetry, Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger’s weighted regression test. The Duval & Tweedie “trim and fill” method was used to adjust the analysis for the effects of publication bias [33].

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

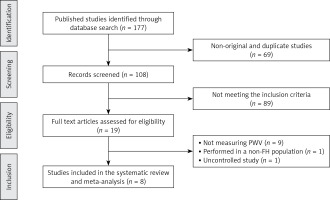

Initially, 177 published studies were identified following a multiple database search. After screening of titles and abstracts and removing non-original studies (n = 69) and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 91), 17 full text articles were carefully assessed and reviewed for eligibility. Of these, 11 clinical trials were excluded for not measuring PWV (n = 9), because they were performed in a non-FH population (n = 1), or were uncontrolled studies (n = 1), thus leaving 8 eligible articles for the present meta-analysis (Figure 1).

A total of 317 patients with FH and 244 normocholesterolemic controls were included in this meta-analysis. Included studies were published between 2007 and 2016. FH populations from the following countries were included: Brazil, Greece, Italy, Russia, Poland, Taiwan and the UK. There were 4 studies performed on heterozygous and 4 on unspecified type of FH patients. Study design of selected studies was cross-sectional and case-control.

Concerning the diagnosis of FH, four studies used gene mutation analysis, two studies used the Simon Broome criteria, one study used the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria, and another study used the U.S.MEDPED criteria (Table I).

Table I

Demographic characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Study design | Target population | Type of FH | Diagnostic criteria | N | Study groups | Age [years] | Female n (%) | BMI [kg/m2] | IMT [mm] | Type of vessel | PWV [m/s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng et al. (2007) | Cross-sectional comparative | FH subjects | Heterozygous | Gene mutation analysis | 35 17 | FH group Control | 37.1 ±17.8 33.0 ±15.0 | 17 (48.5) 9 (52.9) | 22.1 ±4.7 21.5 ±3.6 | 1.09 ±0.90 0.67 ±0.15 | Brachial artery | 12.5 ±2.9 11.9 ±2.3 |

| Ellins et al. (2016) | Case-control | FH patients | Unspecified | Simon Broome criteria | 22 22 | FH group Control | ND ND | ND ND | ND ND | ND ND | Right brachial artery | 7.7 ±0.8 8.2 ±0.9 |

| Ershova et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional comparative | FH patients | Heterozygous | Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria | 66 57 | FH group Control | 38 (27–48)* 33 (23–42)* | 40 (60.6) 31 (54.3) | 24.3 (21.5–28.2)* 22.5 (20.4–25.4)* | 0.55 (0.50–0.70)* 0.51 (0.46–0.64)* | Carotid artery | 5.4 (4.5–6.4)* 4.7 (4.2–5.4)* |

| Lewandowski et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional comparative | FH patients | Unspecified | Gene mutation analysis | 21 19 20 | FH group Non–FH group Control | 38.9 ±7.4 45.4 ±6.7 41.6 ±7.8 | 10 (47.6) 8 (42.1) 10 (50.0) | 26.1 ±4.1 26.0 ±3.2 24.6 ±4.3 | ND ND ND | Right brachial artery | 8.7 ±3.3 9.5 ±3.5 10.2 ±4.1 |

| Martinez et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional comparative | FH subjects | Unspecified | U.S.MEDPED criteria | 89 31 | FH group Control | 39 ±14 40 ±12 | 55 (61.7) 15 (48.3) | 25.9 ±4.9 24.7 ±3.5 | 0.65 ±0.16 0.59 ±0.11 | Carotid–femoral arteries | 9.2 ±1.5 8.5 ±1.0 |

| Riggio et al. (2010) | Cross-sectional comparative | Children with FH | Heterozygous | Gene mutation analysis | 18 26 18 | FH group PH group Control | 11.8 ±2.8 9.5 ±5.6 9.9 ±1.8 | 12 (66.6) 16 (61.5) 11 (61.1) | 24 ±3 25 ±6 23.6 ±6.3 | 0.45 ±0.07 0.46 ±0.06 0.45 ±0.09 | Carotid artery | 4.7 ±0.7 4.1 ±0.5 3.6 ±0.5 |

| Vlahos et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional comparative | Children with FH | Heterozygous | Gene mutation analysis | 30 30 | FH group Control | 12 ±2 12 ±2 | 13 (43.3) 13 (43.3) | 19.8 ±4.0 19.3 ±2.8 | 0.46 ±0.05 0.45 ±0.03 | Carotid–femoral arteries | 5.3 ±0.9 5.6 ±0.9 |

| Waluś-Miarka et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional comparative | Young patients with FH | Unspecified | Simon Broome criteria | 36 49 | FH group Control | 27.3 ±6.6 25.2 ±6.7 | ND ND | 23.6 ±3.9 23.2 ±4.5 | 0.60 ±0.19 0.53 ±0.07 | Carotid–femoral arteries | 8.4 ±1.5 8.5 ±1.1 |

PWV assay methods

Different methods were used to measure the PWV. In this regard, one study used a VP-1000 device (Colin Corporation, Komaki, Japan) to measure the brachial-ankle PWV. One study determined the PWV with a Vicorder device (Skidmore medical, Bristol, UK) while another study used echo-tracking software (Aloka Prosound Alpha7, Hitachi-Aloka, Tokyo, Japan) and a 14 MHz linear-type probe to assess the PWV. Two studies measured the PWV using the echo-tracking method with Aloka SSD-Alpha 10-Miro and the automatic system of ultrasound vascular evaluation. Furthermore, two other studies evaluated the PWV with a Complior device (Colson, Garges les Gonesses, France). Finally, Vlahos et al. [34] used echo-Doppler ultrasound (Ultrasound ATL, HDI 5000, Bothell, WA) to assess the PWV.

Quality assessment of the included studies

Most of the studies exhibited sufficient information concerning definition of cases and controls, but there was a lack of information regarding representativeness of the cases and selection of controls. Other parameters for quality assessment of the included studies are shown in Table II.

Table II

Quality of bias assessment of the included studies according to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale

| Study | Selection | Comparability† | Exposure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case definition | Representativeness of the cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Comparability of cases and controls | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method of ascertainment | Non-response rate | |

| Cheng et al. (2007) | * | – | – | * | ** | * | * | – |

| Ellins et al. (2016) | * | – | – | – | ** | – | * | – |

| Ershova et al. (2016) | * | – | – | * | ** | * | * | – |

| Lewandowski et al. (2014) | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | – |

| Martinez et al. (2008) | * | * | – | * | ** | * | * | – |

| Riggio et al. (2010) | * | – | – | – | ** | * | * | – |

| Vlahos et al. (2014) | * | * | – | * | ** | * | * | – |

| Waluś-Miarka et al. (2013) | * | – | – | * | ** | * | * | – |

Comparison of PWV between patients with FH and controls

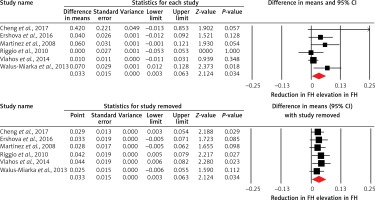

Overall, 8 studies compared PWV between patients with FH and normocholesterolemic controls. The meta-analysis did not suggest a significantly altered PWV in FH patients versus controls (WMD = 0.17 m/s, 95% CI: –0.31, 0.65, p = 0.489; I2 = 80.15%) (Figure 2). This result was robust in the sensitivity analysis and its significance was not influenced after omitting each of the included studies from the meta-analysis (Figure 2). In the subgroup analysis, there was no significant difference between subgroups of studies in patients ≤ 20 years (WMD = 0.41 m/s, 95% CI: –0.95, 1.76, p = 0.557; I2 = 94.41%) and > 20 years (WMD = 0.07 m/s, 95% CI: –0.39, 0.53, p = 0.758; I2 = 62.72%) (between-group p = 0.647). Likewise, the estimated effect size was not significantly different between patients with FH and controls in the subgroup of studies in confirmed HeFH patients (WMD = 0.40 m/s, 95% CI: –0.29, 1.09, p = 0.253; I2 = 83.78%).

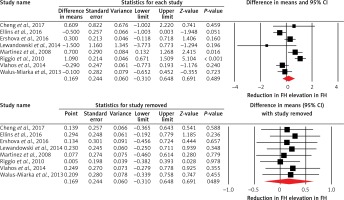

Figure 2

Forest plot displaying weighted mean difference and 95% confidence intervals of pulse wave velocity between patients with familial hypercholesterolemia and unaffected controls. Lower plot shows leave-one-out sensitivity analysis

Among the included studies, 6 studies also assessed IMT. Subanalysis of these studies indicated an increased IMT in FH patients when compared with controls (WMD = 0.03 mm, 95% CI: 0.003, 0.06, p = 0.034; I2 = 48.95%) (Figure 3). However, the effect size was sensitive to some of the included studies, as shown in Figure 3.

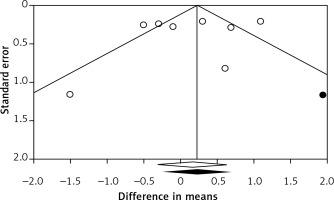

Publication bias

There was no evidence of publication bias according to the results of Egger’s linear regression (intercept = –1.32, standard error = 2.16, 95% CI: –6.61, 3.97, t = 0.61, df = 6, two-tailed p = 0.565) and Begg’s rank correlation tests (Kendall’s τ with continuity correction = –0.04, z = 0.12, two-tailed p = 0.902; Figure 4). The funnel plot of the study standard error by effect size (WMD) was slightly asymmetric. This asymmetry was addressed by imputing one potentially missing study using the “trim and fill” method. After imputation, the effect size was changed to 0.23 (95% CI: –0.25, 0.71) and remained non-significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first meta-analysis evaluating PWV as a measure of arterial stiffness in patients with FH. The results of this meta-analysis suggest that FH patients do not have significantly altered PWV compared with controls. However, a subanalysis of studies in which IMT was measured indicates that IMT is increased in FH patients when compared with controls.

This meta-analysis did not include the most recently published results of a study performed on 245 patients with FH, which suggested a different conclusion, i.e. that arterial stiffness assessed by the PWV was significantly associated with the presence of coronary heart disease in patients with FH [35]. Nevertheless, there was no comparison with normocholesterolemic controls in the study published by Tada et al. [35]. Another recent study on 66 patients with FH and their 57 first-degree relatives without FH demonstrated that treatment-naïve FH patients had stiffer carotid arteries than their relatives but showed no difference in aortic stiffness [36]. Furthermore, in another relatively small study (81 FH patients compared with normal subjects), these markers poorly correlated among each other in univariate analysis and this correlation disappeared after adjustment for confounders [37]. Other authors could also not find any significant difference in arterial stiffness (assessed by pulse wave analysis using the echo tracking method and photoplethysmographic pulse waveform analysis) between patients with and without FH [38].

There are reports that arterial stiffness measured by PWV, but not IMT, is increased in untreated hypercholesterolemic children (almost half of them had FH) when compared with age- and sex-matched controls [39]. When mentioning studies in children with FH, a relatively recent study found no significant difference either in arterial stiffness or in carotid IMT between HeFH children and their sex- and age-matched controls without FH [34]. However, a very recent study showed that in HeFH children carotid IMT was significantly greater at baseline when compared with unaffected siblings [40]. The same study indicated that treatment with rosuvastatin for two years resulted in significantly less progression of increased carotid IMT in children with HeFH than untreated unaffected siblings and, as a result, no difference in carotid IMT could be detected between these two groups after 2 years. This confirmed earlier studies indicating that the difference in carotid IMT between children with FH and their unaffected siblings may be significant as early as at 8 years of age, that long-term statin treatment (lasting 10 years) initiated during childhood in patients with FH was associated with normalization of carotid IMT progression, and that earlier statin initiation was associated with thinner carotid IMT at follow-up [41, 42].

It could be supposed that long-lasting lipid-lowering treatment might improve PWV in adult patients with FH. Indeed, it was shown that 1 year of cholesterol lowering therapy with statins (simvastatin, atorvastatin 40–80 mg day) in FH patients can decrease the wall stiffness in the carotid and femoral arterial wall and thickness in the common carotid artery [43].

It is well known that adult patients with FH are not at moderate but either at high or at very high ACVD risk, so there is no point in screening them by carotid IMT measurement in order to improve their risk assessment [44–46]. Therefore, the finding of this meta-analysis, that IMT is increased in FH patients compared with controls, is absolutely logical and fits well with the common knowledge about FH. Moreover, a recent study proved that FH patients with a monogenic cause of the disease have a greater carotid IMT and more severe coronary preclinical atherosclerosis than those with a polygenic etiology [47].

Only one meta-analysis which investigated IMT in FH patients compared to normolipidemic controls has been published, 7 years ago. In this meta-analysis, in FH patients both carotid and femoral IMT values were higher [48]. Nevertheless, this meta-analysis was aimed more at proving that treatment with statins can improve arterial function and structure in FH patients in a treatment intensity-related manner. In this context it is interesting to mention that one study proved that not only carotid IMT but also carotid plaques did not differ between long-term statin-treated HeFH patients and healthy controls, suggesting that long-term treatment in these patients can reduce carotid atherosclerosis to the degree of a healthy population [49]. These findings strongly suggest that measuring carotid IMT during follow-up of statin-treated FH patients has limited value [49]. When mentioning measurement of carotid plaques, a very recent study on 225 patients with FH showed that carotid plaque score determined by carotid ultrasonography may provide superior risk stratification in patients with FH compared with carotid IMT [50].

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. Different scores for FH diagnosis as well as different methods for PWV estimation were used in different studies included in the present meta-analysis and there was a lack of information about the duration of lipid-lowering therapy and type of treatment (i.e. statin type and dose, statin and ezetimibe combined treatment, apheresis, PCSK9 inhibitors). These data are important as statins may improve PWV and arterial stiffness [51, 52] while the information on novel lipid-lowering therapies including PCSK9 inhibitors is scant. In this context, PCSK9 inhibitors have been suggested to have additional effects [53, 54] beyond their well-known lipid-lowering properties [55, 56]. Similarly, antihypertensive drugs may differentially affect PWV based on the type and duration of treatment [57–60].

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis suggests that FH patients do not have significantly altered PWV as a measure of arterial stiffness when compared with normocholesterolemic controls. However, a subanalysis of studies, in which IMT was measured, indicates that IMT is increased in FH patients when compared with controls. Given the prevalence and burden of FH [61–63], additional studies are suggested to assess IMT as a risk predictor in FH individuals. Obviously, larger studies evaluating PWV in FH patients compared with controls in order to elucidate the impact of FH on arterial stiffness as measured by PWV, if any, are needed.

Conflict of interest

MB has served on the speaker’s bureau and as an advisory board member for Amgen, Sanofi, Aventis and Lilly. NK has given talks, attended conferences and participated in trials sponsored by Amgen, Angelini, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Galenica, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and WinMedica. KR received a research grant from Sanofi, and served on the speaker’s bureau and as an advisory board member for Sanofi, Astra Zeneca and Pfizer. ZR has received honoraria from Sanofi Aventis and Akcea. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.