Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), as a subset of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, constitutes 95% of all neoplastic tumours in this area. It includes, in descending order of frequency, the following: floor of the mouth, tongue, gingivae, mucous membrane of the cheeks, and palate [1, 2]. Over 263,000 new OSCC cases occur each year globally and they account for 5% of all cancer-related deaths. Men are more often affected than women, especially in the sixth decade of life. However, there is a rapid increase in incidence in those under 50 years of age [3, 4].

This review focuses on the role of the main phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase/serine-threonine kinase (PI3K) / (AKT) signalling pathway components: phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-3-kinase catalytic subunit α (PIK3CA), phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), and AKT proteins in aggressive progression and their prognostic significance in OSCC. This is vital for understanding oral squamous cell cancer biology and may be useful in indicating the direction that new treatments should take, by using PI3K pathway inhibitors in targeted molecular therapy for patients with OSCC.

Material and methods

For this review, a systematic search of the literature was conducted in the PubMed database to identify papers reporting data about the PIK3CA, AKT, and PTEN genes in OSCC. Keywords “PIK3CA and oral cancer”, “PIK3CA and OSCC”, “PIK3CA and oral squamous cell carcinoma”, “PIK3CA and OSCC and prognostic factor”, “AKT and oral cancer”, “AKT and OSCC”, “AKT and oral squamous cell carcinoma”, “AKT and OSCC and prognostic factor”, “PTEN and oral cancer”, “PTEN and OSCC”, “PTEN and oral squamous cell carcinoma”, and “PTEN and OSCC and prognostic factor” were used. This paper includes studies published before 29 October 2017. The review focused on the PIK3CA, AKT, and PTEN gene mutations as prognostic factors in OSCC, in terms of tumour cell invasion, metastatic capacity, possible re-expression in metastatic tissue, and therapeutic inhibition pathways. Experimental studies and publications referring to human tissue were considered. The following articles were excluded: duplicate records, letters, and papers that did not contain significant information. Based on these criteria, 508 articles were selected for further analysis (exclusion criteria: research not on humans, studies on cell lines and not in English), the first identified study having been published in 2001. From the 508 papers, a total of 35 representative studies were selected as being eligible for the present review about PIK3CA, AKT, and PTEN gene mutations in OSCC (excluding duplicate articles).

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

Oral squamous cell carcinoma can present with a wide range of clinical appearances. Patients and their clinicians frequently underestimate early symptoms of cancer development. The most commonly reported primary lesion is oral mucous ulceration appearing initially as soft tumour, gradually becoming harder and hyperkeratotic with plates and fissures, especially on the tongue. Other symptoms may include pain, Vincent’s symptom, mucous membrane redness, muscle contracture, teeth loosening and displacement, trismus, halitosis, dysphagia, and odynophagia. Some of these symptoms may resemble an odontogenic inflammation, leading to incorrect treatment, e.g. with antibiotics or tooth extractions, which may contribute to the spread of the neoplasm. The life-saving therapy is therefore delayed, and although the oral cavity is easily accessible to physical examination these malignancies are often not detected until a late stage. In such cases, only palliative therapy can be given. Early diagnosis is very important in limiting tumour spread [3–5].

The development of oral cancer is affected by a variety of factors. Smoking, betel nut chewing, and alcohol abuse are well-known risk factors for the development of pre-cancerous lesions (leukoplakia, erythroplakia, hyperkeratosis, dysplasia, lichen planus). Infection by human papilloma virus (HPV), Ebstein-Barr virus, or Candidas have also emerged as risk factors for OSCC. There is an increase in oral cancer incidence in younger age groups, particularly in cases of the base of the tongue region. Human papilloma virus infection is considered a sexually transmitted disease, and sexual practices in the younger population could increase the risk of HPV-associated oral infections. Moreover, HPV status dramatically changes the clinical scenario in oral cancer patients. Human papilloma virus-positive tumours were shown to have a better oncological outcome compared to the negative, ones especially compared to cancer associated with smoking [4–10]. Other factors increasing OSCC risk include the following: inadequate oral hygiene, irritation caused by dentures, immunological defects, eating disorders, oesophageal reflux disease, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, and occupational exposure to asbestos, chromium, and formaldehyde [4, 8].

The first-line therapy for oral cavity cancer is surgical treatment. However, in more advanced OSCCs, a nonsurgical approach is used in most centres. In spite of the progress made in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the 5-year survival rates have remained stable over the last decade [10]. Unsatisfactory treatment outcomes, high mortality, and poor prognosis lead to the development of personalised therapies focused on specific molecular markers. The inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) by cetuximab has been seen to improve the clinical outcome in recurrent and metastatic OSCC [11, 12]. A similar effect might be achieved by blocking the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Therefore, it is essential to describe potential molecular markers and their predictive and prognostic significance. It is also crucial to develop methods to detect these markers, so that they are easy to use in everyday clinical practice without resorting to high-cost methods [13].

Phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase signalling pathway

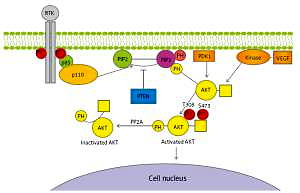

The intracellular signalling pathway of PI3K is involved in the processes of growth, differentiation, intracellular trafficking, migration, and survival of a cell. Moreover, it is a key element in the cellular response to insulin and other growth factors, and it is involved in the aging process [13–15]. The phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase signalling pathway also plays a role in autophagy [16]. It is one of the three basic signalling pathways associated with receptor tyrosine kinase activity (RTK), together with the protein kinase C and Ras/MAPK pathway. Binding RTK with specific ligands results in PI3K pathway activation and generates its critical product – phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3). PIP3 plays a key role as a second messenger, which, due to the presence of pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, is able to bind itself to AKT, tyrosine kinases, or G proteins. Phospholipid PIP3 is found in the cell membrane and can bind with these kinases and G protein by PH domain, resulting in their recruitment near the membrane. The phosphorylation process activates, among others, serine-threonine protein kinase B, known also as AKT, through 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1. AKT phosphorylation occurs at position T308 of tyrosine and S473 of serine, causing a thousand-fold increase in enzymatic activity. In turn, activated AKT protein initiates the transcription of gene encoding for multiple proteins that affect major cellular processes. The concentration of PIP3 is adjusted primarily by means of its dephosphorylation by PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue on chromosome 10). Figure 1 illustrates the PI3K signalling axis in detail [17, 18].

Figure 1

Diagram of phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase/serine-threonine kinase pathway. Receptor tyrosine kinase activates phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit p110 and regulatory subunit p85 that converts phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate and causes serine-threonine kinase membrane recruitment and activation, and hence regulating transcription in the cell nucleus

RTK – receptor tyrosine kinase, PTEN – phosphatase and tensin homologue encoded on chromosome 10, PIP2 – phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, PIP3 – phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, PDK1 – 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1, PP2A – protein phosphatase 2, PH – pleckstrin homology domain, AKT – serine-threonine kinase, T308 –threonine 308 phosphorylation site at the AKT kinase catalytic domain, S473 – serine 473 phosphorylation site at the AKT kinase regulatory domain, PO4 – phosphate group, VEGF – vascular endothelial growth factor, p85 – regulatory domain of phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase, p110 – catalytic domain of phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase, PTEN – phosphatase and tensin homologue protein acts as a phosphatase to dephosphorylate, PIP3 – this dephosphorylation results in inhibition of the AKT signalling pathway.

The impact of PI3K signalling pathway deregulation on tumourigenesis has been recognised since the 1970s [19]. All of the major elements of this pathway have been found to be mutated or amplified in a broad range of cancers. Genetic alterations of PI3K/AKT pathway have been shown to promote aberrant cell growth and induce tumourigenesis [20]. The best known include the loss-of-function mutations in suppressor gene PTEN, leading to the loss of its activity and consequent activation of cell proliferation stimulation along the whole pathway. These have been described mainly in endometrial carcinoma, glioblastoma, or prostatic cancer [21–23]. Other well-known include activating point mutations of PIK3CA and AKT gene amplification. The role of these alterations in cancer progression is very complex. There are several theories about its oncogenicity. The coexistence of PTEN gene loss and PIK3CA gene mutations suggests that individual alterations are not completely redundant, but are able to activate non-overlapping pathways [24].

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-3-kinase catalytic subunit α

Phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase is the lipid kinase that phosphorylates the hydroxyl group at position 3 of the inositol ring of phosphatidylinositol [25, 26]. It is divided into three classes: I (A and B), II, and III. Class IA PI3K is a heterodimer composed of two subunits: regulatory (p85) and catalytic (p110). There are three isoforms of the catalytic subunit: p110α, p110β, and p110δ, being expressed by PIK3CA (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit α), PIK3CB (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit β), and PIK3CD (phosphoinositide-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit δ) genes, respectively. Similarly, regulatory subunits exist in three isoforms: p85α, p85β, and p85γ encoded by PIK3R1, PIK3R2, and PIK3R3 genes, respectively. Class IB is composed of catalytic subunit p110γ and regulatory 1 – p101 or its homologous forms p84 and p87PIKAP. IA kinases are activated by interaction with RTK, and IB by G protein-coupled receptors. Class II PI3Ks contains catalytic subunit p110 only, which is comprised of three isoforms: PIK3C2α, PIK3C2β, and PIK3C2γ. Class III consists of one Vps34 (vacuolar protein-sorting defective 34) molecule (Table I) [17, 26].

Table I

Phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase family

The oncogenic potential of the PIK3CA gene alterations is associated, inter alia, with tumour insensitivity to insulin and thus to the reduction of energy consumption in the cells. The most common point mutations in a gene that have a proven carcinogenic potential are so-called hotspot mutations: H1047R (exon 20), E542K, and E545K (exon 9) (Table II) [17, 27–30]. Mutations in the PIK3CA gene also occur within exons 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7 [31]. It is also believed that amplification of the PIK3CA gene can lead to neoplastic transformation [26].

Table II

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-3-kinase catalytic subunit α and phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 genetic alterations in oral squamous cell carcinomas – review of current studies

| No. | Reference | Total patient number | Point mutations | PIK3CA amplification | Loss of PTEN (deletions) | Methods | Prognostic significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA | PTEN | AKT | |||||||

| 1 | Shin et al., 2002 [71] | 86 | NE | 4/86 (4.65%) | NE | NE | NE | RT-PCR, real-time PCR | NE |

| 2 | Mavros A et al., 2002 [70] | 50 | NE | 0/50 (0%) | NE | NE | NE | Sanger DNA sequencing multiplex PCR | NE |

| 3 | Kozaki K et al., 2006 [41] | 108 | 8/108 (7.4%) | NE | NE | 18/108 (16.7%) | NE | Real-time PCR | NE |

| 4 | Qiu W et al., 2006 [31] | 8 | 0/8 (0%) | NE | NE | NE | NE | Sanger DNA sequencing | NE |

| 5 | Fenic I et al., 2007 [42] | 12 | 1/12 (8.3%) | NE | NE | 3/12 (9.0%) | NE | RT-PCR, real-time PCR | NE |

| 6 | Bruckman KC et al., 2010 [43] | 35 | 1/35 (2.9%) | NE | NE | NE | NE | Sanger DNA sequencing | NE |

| 7 | Kostakis GC et al., 2010 [44] | 86 | 0/86 (0%) | NE | NE | NE | NE | Sanger DNA sequencing | NE |

| 8 | Cohen Y et al., 2011 [45] | 45 | 4/37 (10.8%) | 0/37 (0%) | 0/37 (0%) | NE | NE | MALDI-TOF-MS | NE |

| 9 | Tu HF et al., 2011 [46] | 82 | 4/37 (10.8%) | NE | NE | 42/82 (50%) | NE | q-PCR | NE |

| 10 | Suda T et al., 2012 [47] | 31 | 2/31 (6.5%) | NE | NE | 9/31 (32.5%) | NE | Sanger DNA sequencing qPCR | NE |

| 11 | Chang YS et al., 2014 [30] | 79 | 11/79 (13.92%) | NE | NE | NE | NE | HRM | NS p=0.094 |

| 12 | Shah S et al., 2015 [48] | 50 | 2/50 (4.0%) | NE | NE | NE | NE | Sanger DNA sequencing | NE |

| 13 | Arunkumar G et al., 2017 [50] | 96 | 0/96 (0%) | NE | NE | NE | NE | RT-PCR | NE |

| 14 | Shah S et al., 2017 [49] | 59 | NE | NE | NE | NE | 3/59 (5.0%) | Sanger DNA sequencing | NE |

The presence of point mutations and amplifications of the PIK3CA gene mapped to the 3q26.32 locus [31] has been demonstrated in numerous malignancies, such as glioblastoma, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, ovary and cervix cancers, larynx and pharynx cancers, prostate cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease), leukaemia, malignant melanoma, or primary liver cancer [17, 25, 31–40].

The literature documenting PIK3CA genetic aberration in OSCCs is limited. PIK3CA gene mutations in SCC of the head and neck were first reported in 2006 by Qiu et al., with a mutation frequency of 10.8% [31]. There were only 8 cases of OSCC, and PIK3CA gene mutations were not identified in this subgroup. The highest mutation rate was reported by Chang et al. (13.92%) [30]. In other studies the percentage of common PIK3CA gene mutations range from 0 to 10.8% [30, 31, 41–49]. Similar discrepancies were found in studies evaluating PIK3CA gene amplification. This variation in frequency could result from the sample size, the method used for mutation analysis, or different ethnicity of patients in the studies. The last of the mentioned causes seems plausible, since in a recent study on a South Indian population, PIK3CA gene mutations were not found at all [50]. Most of the reports show no significant association with the clinical data of the patients, such as age, cigarette smoking, gender, location of the tumour, histologic grading, and gene status. Only in the work carried out by Kozaki et al., which had the largest number of patients, did mutation frequency correlate positively with the stage of the disease (p = 0.042) [41]. On the other hand, Fenic et al. found that PIK3CA gene amplifications correlate with histological grading [42]. Survival analysis was performed only in a few reports, and these disclosed no significant correlation. Additionally, the greatest increase in the PIK3CA gene mutations is observed in early stages of tumour development [51].

The incidence of the PIK3CA gene amplification in the studies on OSCC conducted so far was found in 9.0% to 50.0% of cases [40–42, 46]. Such differences may be caused by different study groups and different methods used to evaluate PIK3CA gene copy number.

Serine-threonine kinase

The serine-threonine protein kinase is an essential effector protein of the PI3K pathway and a major mediator of the survival signal that protects cells from apoptosis. It is therefore a potentially important therapeutic target [52]. There are three isoforms of this kinase: AKT 1 (PKB α), AKT 2 (PKB β), and AKT 3 (PKB γ). The first two kinases can be found in most cells, while the presence of AKT3 is restricted to the brain, testis, heart, kidney, lung, and skeletal muscle [53]. It is believed that each isoform participates in different processes. AKT1 affects cell survival and growth, AKT2 controls insulin signalling in the liver cells and skeletal muscles, and AKT3 affects the development of the brain [54–56].

The point mutation (nucleotide 49) in the AKT1 gene, which results in the conversion of glutamic acid (E) to lysine (K) in the protein chain, causes the membrane translocation of the AKT1 protein and its constitutive activation [45, 52]. Gene amplification is one of the basic mechanisms involved in the activation of these oncogenes. Correlation between the presence of AKT gene mutations and poor prognosis was observed in cancer of the oral cavity, skin, prostate, pancreas, liver, stomach, endometrium, breast, brain, and haematological neoplasm [22, 40, 41, 52–55, 57–63].

Five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the AKT1 gene were investigated and genotyped by Sequenom Mass Array and iPLEX-MALDITOF technology. Polymorphisms rs1130214 and rs3803300 in the AKT1 gene were associated with OSCC susceptibility. Moreover, CT genotype of the SNP rs3730358 was associated with higher risk of OSCC progression in the Chinese Han population [55]. In one study by Cohen et al. no mutations in the AKT1 gene were found. Due to its impact on patient survival in the majority of cancers, which has been documented, they should be taken into consideration in further research on OSCC [45].

Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10

PTEN acts as a PI3K/AKT signalling pathway inhibitor through the dephosphorylation of PIP3, reducing its concentration within the cell. This results in a downregulation of AKT-dependent signalling cascade through AKT protein dephosphorylation. Conversely, loss of PTEN gene expression results in increased AKT activity and continued cell proliferation. Deletions and missense point mutations leading to PTEN gene inactivation are the most frequently observed genetic aberrations found in a variety of neoplasms such as prostatic, breast, lung, endometrial, and colorectal cancers or glioblastomas [21, 23, 26, 64–68]. Total suppression of the PTEN gene expression is lethal to embryonic cells, and partial suppression leads to carcinogenesis [40]. The prognostic significance of PTEN gene inactivation has been described mainly in uterus, breast, prostate, and lung cancer or malignant melanoma [21, 23, 65, 66, 69].

To date, there have been very few studies reporting PTEN genetic aberrations in OSCC. In some studies they were not detected [45, 70]. On the other hand, Shin et al. reported PTEN gene point mutation frequency in 4.65% of cases from which four were identified as missense mutations and one as frameshift mutation in four oral cancers [71]. In recently published data on an Indian population Shah et al. documented PTEN intronic deletions in 3 cases, without any significant correlation with gender, tumour size, stage, or grade. In this study no mutations were found in the coding region of the PTEN gene [48].

PTEN protein loss, evaluated by measuring protein status by immunohistochemistry, is not a rare finding. Negative PTEN gene expression was found in 29–96.3% of OSCC in different study groups [72–80]. According to Lee et al. the survival time was shorter in PTEN-negative patients (p < 0.05) [72]. There are data suggesting that PTEN protein loss is a more common factor in poorly differentiated tumours [73, 76] and in advanced tumour stages [75, 80]. This leads to the conclusion that PTEN loss might be involved in OSCC tumour progression and the development of metastases. Moreover, loss of PTEN is more frequent in HPV-negative tumours [76]. Table III shows immunohistochemical evaluation of PTEN protein loss.

Table III

Immunohistochemical evaluation of phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 protein loss

| No. | References | Total patient number | Loss of PTEN | PTEN loss correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | Grade | Stage | Nodal metastases | Prognostic significance | ||||

| 1 | Lee JI et al., 2001 [72] | 41 | 12 (29%) | p < 0.05 | NS p = 0.16 | NS p = 0.48 | NS p = 0.48 | NS p = 0.05 | OS p < 0.05 |

| 2 | Squarize CH et al., 2002 [73] | 22 | 7 (32%) | NE | NE | p < 0.005 | NE | NE | NE |

| 3 | Kurasawa Y et al., 2008 [74] | 113 | NR | NE | NE | NS p = 0.373 | NS | NE | NE |

| 4 | Rahmani A et al., 2012 [75] | 60 | 34 (56.6%) | NS p > 0.05 | NS p > 0.05 | p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 | NE |

| 5 | Won SH et al., 2012 [76] | 60 | 58 (96.3%) | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NS |

| 6 | Monteiro LS et al., 2014 [77] | 72 | 22 (30.6%) | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | OS p = 0.908 |

| 7 | Pickhard A et al., 2014 [78] | 33 | NR | NE | NE | p < 0.05 | NE | NS | NS |

| 8 | Jasphin SS et al., 2016 [79] | 30 | NR | NE | NE | NS p = 0.174 | NE | NE | NE |

| 9 | Zhao J et al., 2017 [80] | 90 | 28 (31.1%) | NS p = 0.133 | NS p = 0.149 | p < 0.05 | p < 0.01 | NE | OS p < 0.001 |

PTEN gene point mutations and deletions in OSCC seem to be rare events, demonstrating that they might not comprise a direct factor responsible for PTEN protein downregulation. On the contrary, PTEN loss, evaluated by means of immunohistochemistry, is a common finding, indicating that indirect inactivation (e.g. posttranslational modifications) might be a mechanism leading to PTEN protein loss. This indicates that PTEN protein IHC could be an excellent tumour marker in routine clinical practice [79].

Contemporary studies on the occurrence of PIK3CA, AKT, and PTEN gene mutations in OSCC are shown in Table II.

PIK3CA/AKT/PTEN inhibition in oral squamous cell carcinoma

Oral squamous cell carcinoma treatment modality depends strongly on the cancer stage, with surgery being the preferred approach in almost all stages. For patients with multiple node metastases or extracapsular spread, adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy is recommended. Targeted therapy for oral cancer is still a relatively new concept and needs further investigation. The most frequently studied anti-EGFR therapies have yielded little to no efficacy in clinical trials, neither as a radiation-sensitising agent nor in patients with recurrent or metastatic disease [81]. Recent study conducted in vitro and in vivo revealed that the addition of ALK inhibitors to anti-EGFR agents might enhance the efficacy of EGFR-targeted therapies [82]. Even though anti-EGFR treatment has been introduced in a therapy of advanced OSCCs, primary resistance to anti-EGFR agents poses a serious problem. Some studies reported that pAKT immunohistochemical positivity predicted a better response to cetuximab treatment, whereas loss of PTEN did not correlate with response to cetuximab [83]. On the other hand, the study of da Costa et al. showed that loss of PTEN gene expression predicted increased overall survival (OS) and increased progression-free survival (PFS) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) (including the set of OSCC) in patients treated with palliative chemotherapy and cetuximab [84].

Other personalised strategies require investigation for improvement of OSCC therapy results.

PI3K inhibitors have demonstrated antiproliferative, pro-apoptotic, and antitumour activity in a range of preclinical cancer models, as a single agent or in combination with other anticancer therapies. PI3KCA gene mutation, and probably amplification, cause pathway activation and may predict response to PI3K inhibitors. Nowadays, a number of selective, directed against PI3K-α isoform, and non-specific inhibitors of PI3K, have been introduced into clinical trials as antitumour therapies in several solid neoplasms [85]. Data on the testing of PI3K inhibitors in OSCC is very scarce. In most of the clinical trials the results were disappointing, without significant improvement of PFS or OS [86, 87]. In one of the studies, a patient who achieved a partial response had both the point mutation and the amplification of PIK3CA gene [87]. In a randomised phase II trial of cetuximab, with or without PX-866, conducted by Jimeno et al., among patients with PIK3CA gene mutations, none responded to anti-PI3K therapy [88]. However, a currently published randomised phase 2 study of BERIL-1 revealed that a combination of buparlisib (pan PI3K inhibitor) and paclitaxel might serve as an effective second-line therapy for patients with recurrent or metastatic HNSCC. The study included 46 OSCC patients [89]. More studies are needed to confirm the clinical effectiveness of these drugs in OSCC along with identification of predictive biomarkers for better personalisation of these therapies.

There are numerous AKT inhibitors tested in preclinical models, but few of them have been admitted to clinical evaluation. Results of these studies emphasise that AKT inhibitors would be most useful in combination with other targeted therapies [56]. At present, there are no clinical report that include anti-AKT treatment of OSCC.

PI3K/AKT/PTEN inhibitors were investigated in preclinical models in HNSCC, similarly to EGFR inhibitors, in terms of radiosensitivity, with promising results [90]. There are reports of research conducted in vitro that PI3K inhibitors may increase the cytotoxic effects of anthracycline-based chemotherapy [91]. High PTEN gene expression was also indicated as a possible marker to predict the benefit from accelerated postoperative HNSCC radiotherapy [90].

There are very few clinical data on the toxicity of PI3K/AKT inhibitors. They have a narrow therapeutic window. Side effects that can occur during therapy include elevated liver enzymes, hyperglycaemia, mood disorders (anxiety, depression), skin toxicity (rush), diarrhoea, and fatigue. Inadequate dosing and subsequent reduced anti-tumour activity may also occur. At present, possible use of tumour-specific PI3K inhibition via nanoparticle-targeted delivery in head and neck cancer is being looked into [92, 93].

Discussion

Oral squamous cell carcinoma remains a significant health problem because it tends to be diagnosed at an advanced stage. Although survival has improved due to recent advances in treatment, the prognosis for patients presenting with advanced OSCC remains poor. Current studies on various malignancies, including oral squamous cell carcinoma, focus on molecular biomarkers of prognostic, and predictive significance. PI3K/AKT/PTEN is the second most frequently mutated signalling pathway in human cancer and changes in the pathway are likely to play an important role in tumour cell growth, survival, and metabolism. In various types of carcinoma, such as lung, prostate, breast, or colon carcinoma, a relationship between the presence of PIK3CA, AKT, or PTEN gene mutations and cancer progression has been demonstrated. Moreover, there is documented evidence that in some cases they play a role as independent determinants associated with poor prognosis and reduced 5-year survival of patients. Detection of PIK3CA, AKT, or PTEN genetic alterations could be important in cancer therapy, because their status may be indicative of the resistance of tumour cells to conventional chemotherapy methods, e.g. 5-fluorouracil, or may be used as a predictive molecular marker for a particular targeted therapy [94].

In conclusion, our current review demonstrates the incidence and prognostic significance of the main PI3K/AKT/PTEN signalling pathway components. In view of the importance of PI3K/AKT/PTEN in tumour progression, the dysregulation of PIK3CA and PTEN genes detected in OSCC may help to identify new targeted therapies. Due to AKT gene activation in many types of cancer and its documented action as a poor prognostic factor in various cancers, an analysis of AKT gene abnormalities in OSCC needs further investigation.