Introduction

Communication with a patient about dying and his/her death is an integral part of palliative care. It is indispensable in many areas of medicine as an element of holistic care, although a palliative care professional is particularly exposed to end-of-life issues raised by the patient. Dr. Balfour Mount, one of the founders of palliative care, says that people who provide health care are so afraid of death themselves that fear compromises their ability to administer to the needs of terminally ill patients [1]. The problem is significant and may be captured by quoting Dr. Mount’s words: “If we have unconscious angst provoked by the patient, it is little wonder that we are less well primed to see and assess what their needs are. Death-related anxiety is an important part of our psychic milieu. We are also uniquely unprepared as a society to cope with death. This is why the needs go unmet, and the suffering is unnecessary” [1].

Patients have a right to be honestly informed about their state of health. In the case of an unfavourable prognosis, a physician ought to inform a patient about it with tact and respect [2]. Breaking bad news to patients in an appropriate manner is not an optional skill but an essential part of professional practice [3]. Patients not only want to get information about the diagnosis but also the chances for a cure, the treatment and its alternatives, side effects of the therapy, and a realistic estimate of the expected duration of life [4, 5].

A palliative care practitioner should have general communication skills, including the essentials of breaking bad news. The study of life would be incomplete without the study of death and the dying process, the grieving process, and the social attitudes toward death, e.g. in the form of workshops on the principles of thanatology and communication to make medical training holistic [6]. These issues should be an element of undergraduate educational programs, as a preparation to face the problems of the patient’s suffering and death. Practical training sessions on breaking bad news on diagnosis and prognosis, and sufficient time dedicated to communication skills during undergraduate education are also important.

There are many factors that have an impact on the attitude of physicians towards breaking bad news, such as gender, empathy, parental death, parental anxiety, communication skills, socio-economic status, cultural conditions, spirituality, religious beliefs, the cohesion of philosophy of life (conformity between one’s conduct and convictions), fatigue, burnout, and the attitude towards one’s own death [7]. Inexperienced doctors are afflicted by stress resulting from breaking bad news more than experienced ones; however, poor communication is not strictly related to inexperience with breaking bad news [8, 9]. Breaking bad news entails strong emotions such as anxiety, the feeling of accountability for the distress of the patient, or fear of his/her negative response, which may result in a reluctance to reveal unpleasant information [10]. Physicians may refrain from informing patients properly, even if patients express their strong will to know the diagnosis and the prognosis as much as possible [5, 11].

Fear of death and a low level of determination (the strength of confidence) of philosophy of life may restrain medical professionals from breaking bad news to patients [12]. It may also result in physicians’ inadequate reactions to death and dying, which will affect proper communication with the patient because the fear may be expressed in the physician’s gestures and postures [13, 14].

This study aimed to investigate the influence of philosophy of life and fear of death among physicians on the ability to effectively communicate with patients about dying and death. Additionally, a comparison between palliative care physicians and internal medicine practitioners was performed in order to find possible differences and specific needs of these professionals regarding preparation for breaking bad news.

Material and methods

The questionnaire-based survey was performed among palliative care physicians and internal medicine practitioner groups attending post-graduate courses on palliative care in Poland. The questionnaire (Table I) was designed by the authors and consisted of seven questions in Polish, of which the first four were validated (preliminary testing and test-retest reliability) in a previously performed study [12].

Table I

The questionnaire and the results for internal medicine practitioners (INT) vs. palliative care physicians (PCP)

The questions were formulated based on the training module on communication for students before graduation and physicians. They referred to the aspects that had been raising controversies most often. A four-point ordinal scale was used for questions Q1 to Q5 (definitely not – 0, rather not – 1, rather yes – 2, definitely yes – 3). The participants took part in the survey voluntarily, upon informed consent, and were advised to omit the questions for which they would rather not give an answer or were uncertain. Verbatim answers for open-ended questions were collected and analysed for Q6 and Q7 as well.

Statistical analysis

In the descriptive analysis, the absolute frequency was used. The statistical dependence between non-parametric (ordinal numeric) measures was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests were applied for the statistical analysis of non-parametric data. Frequency analysis was performed using the χ2 test, V-test, and Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. P-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Data were analysed using Statistica 13 (TIBCO Software Inc.).

Results

The results are presented in Table I.

Demography and work experience

In total 102 questionnaires were filled in by 38 palliative care physicians and 64 internal medicine practitioners. Although participation in the survey was voluntary, all the participants that had been asked expressed the will to participate in the survey. Sixty-two respondents (63%) were women, with no statistical difference between palliative care physicians and internal medicine practitioner groups. The average age was 34.6 (95% CI: 32.9–36.4) years. Palliative care physicians were statistically older (43.6 years; 95% CI: 40.8–46.4) than internal medicine practitioners (29.3 years; 95% CI: 28.7–29.9); p < 0.00001. As expected, they also had longer working tenure (17.8 years; 95% CI: 15.2–20.3) than their internal medicine colleagues (3.9 years; 95% CI: 3.4–4.4); p < 0.00001. The average tenure in palliative care of palliative care physicians was 5.2 years (95% CI: 3.6–6.9).

Determination (the strength of confidence) of philosophy of life and religiousness

Question “Q4. Are you a religious person?” tested both the level of determination of philosophy of life and the level of religiousness (Table I). 37.3% of respondents regarded themselves as deeply religious (Q4. answer D); significantly more palliative care physicians (53%) than internal medicine practitioners (28%) regarded themselves as deeply religious (p = 0.007). 49% had a high level of determination of declared (religious or secular) philosophy of life (Q4. answers B and D), with no statistical differences between the groups. The age and the number of working years did not correlate with determination of philosophy of life or religiousness. However, the level of determination of philosophy of life (but not religiousness) positively correlated with the number of working years in palliative care (r = 0.23, p < 0.05), particularly among the physicians working > 5 years in palliative care (Table II).

Table II

Correlation coefficients

[i] WY – working years as a physician, WY > 5 – working years as a physician > 5, WY (PC) – working years in palliative care > 5, WY (PC > 5)– working years in palliative care > 5. Q1 – Should the patient be informed about unfavourable prognosis and upcoming death? [0–3]. Q2 – If there were only 2 weeks of life left for you, would you like to know about it? [0–3]. Q3 – Do you fear your own death? [0–3]. Q4 (Rel) – Deep/internal religiousness (Q4. answer D) [0/1]. Q4 (Det) – High determination of philosophy of life (Q4. answers B and D) [0/1]. Q5 – Is conversation with a patient on dying and death a problem for you? [0–3].

Fear of own death

64.7% of all respondents declared fear of death (“Q3. Do you fear your own death?”), with more internal medicine practitioners than palliative care physicians doing so (73.4% vs. 50.0%, respectively; p = 0.007). Strong fear of death was declared by 31.3% of internal medicine practitioners and 10.5% of palliative care physicians (p = 0.0288). There was also a negative correlation between fear of death and total number of working years (r = –0.26), working tenure > 5 years (r = –0.25), and working years in palliative care (r = –0.20); p < 0.05.

There was no correlation between fear of death, age, the level of determination of philosophy of life, and the level of religiousness.

91.2% of respondents answered positively to the question “Q2. Would you like to know if there were only 2 months left of your life?”, with no statistically significant differences between studied groups. The will to know about one’s own upcoming death was statistically stronger in physicians working for over 5 years.

95.1% of respondents positively answered the question: “Q1. Should a patient be informed about unfavourable prognosis and upcoming death?”, and it did not correlate with any variables except for the will to know about one’s own upcoming death (r = 0.33, p < 0.05).

Conversation with a patient as a problem

For 64.7% of respondents, conversation with a patient on dying and death was a problem (Q5), and 13.7% of them assessed it as a significant one. More internal medicine practitioners (71.9%) than palliative care physicians (52.6%) regarded such conversations as a difficulty; however, the difference was not statistically significant. For the practitioners with a high level of determination of philosophy of life, such a conversation was less difficult (r = –0.23, p < 0.05). Religiousness had no such impact, nor did the age and the number of working years.

There was also a positive correlation between the fear of death and the difficulty of having a conversation about dying and death (r = 0.21, p < 0.05). The conversation with a patient about dying and death appeared to be a problem statistically more often for women (73.4%) than for men (50%), p = 0.0166.

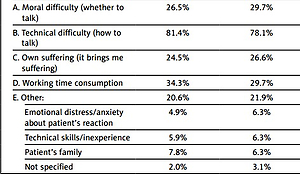

The most frequently indicated problem was lack of skills of effective communication with a patient (87.3%, including verbatim answers). 34.3% of respondents pointed out time consumption, 26.5% of physicians had moral doubts about providing such a conversation, and 24.5% revealed that it caused them personal suffering. Several respondents underlined the problem of the families’ interference in the physician-patient communication process. No statistically significant differences were observed between the studied groups.

Physicians’ needs regarding getting prepared for a conversation with a patient on dying and death

The most frequently expressed need regarding the preparation for breaking bad news was mentoring by an experienced practitioner (75.5% of respondents), followed by training on communication with a patient (68.6%) and the support of a psychologist (54.9%). Other types of help appeared to be less necessary according to respondents. There were statistically insignificant differences between the studied groups. As expected, the need for training on communication skills was presented more often by the persons who recognised technical difficulties as a problem (p = 0.006).

Discussion

There were more women than men among the respondents, which is typical for the medical environment in Poland and an expected result. The palliative care physicians were much (14 years) older than internal medicine practitioners and had longer tenure. This is also typical because most physicians take up palliative medicine as a second specialisation after several years of practice. It is worth mentioning that the average tenure of the palliative care physicians in palliative care was 5 years, which is quite a long time of repeated exposure to dying and death, as these are much more present than in other types of care. Most of the internal medicine practitioners were residents, at an early stage of their practice.

The majority of respondents regarded themselves as religious and less than 20% as atheists. Statistically more palliative care physicians were deeply religious than internal medicine practitioners. Deep (internal) religiousness correlated with the age and, consistently, working years. Half of the respondents declared a high level of determination of philosophy of life (religious or secular). This group may be considered as encompassing persons with a high spiritual orientation. However, there might also be spiritually oriented physicians in the remaining group, but their philosophy of life was not determined. Determination of philosophy of life did not differ between palliative care physicians and internal medicine practitioner groups. It is interesting that the level of determination of philosophy of life (but not religiousness) positively correlated with the number of working years in palliative care, especially when it exceeded five. This finding might suggest that working as a palliative care physician results in the self-determination of the philosophy of life. The repeated and intensive confrontation with dying and death bears reflection on one’s own mortality, the meaning of suffering, and the existential value of life. A recognition of one’s own mortality may allow clinicians to discuss death more comfortably [15]. The findings of this study also suggest the positive effect of repeated exposure on dying and death on the personal spiritual growth of the physician (religious or secular). There is evidence that physicians’ emotional reactions to a patient’s death affect not only patient care but also the personal lives of physicians [16].

Two-thirds of the respondents declared fear of their own death, but the palliative care physicians significantly did so less often. One-third of internal medicine practitioners and only every tenth palliative care physician declared a strong fear of death. It seems that the intensive exposure to dying and death tempers the physician’s own fear of death.

The longer the working years as a physician, the lower the level of fear of death, especially when the tenure exceeds 5 years. This suggests that the first 5 years of physician’s practice in particular may cause distress resulting from the deaths of patients. In this period, psychological and spiritual support, as well as mentoring, may be pivotal for the proper formation of the physician’s attitude. Again, the longer the work in palliative care, the lower the fear of death. It is worth underlining that neither religiousness nor the level of determination of philosophy of life had an impact on fear of death, unlike in the survey performed among students [12]. It seems that other factors modify fear of death along with tenure, and most obvious is the repeated exposure to dying and death.

Almost all respondents would like to be informed about their own impending death regardless of the fear of death, which is typical of a highly-educated population [17]. Their level of autonomy is high, and the need to decide on the last days of life is predominant. This attitude correlates with the level of conviction about the necessity of informing the patient about unfavourable prognosis and upcoming death.

According to almost all physicians, the patient should be informed of bad news. However, according to Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, patients usually know the bad news about impending death, regardless of whether they are informed or not by the physician. What is more, only the patients who have come to terms with their death are able to pass away calmly [18].

Patients expect high levels of both empathy and information quality, no matter how bad the news is [19]. This means the unfavourable information should be delivered but in a proper manner, with empathy and tactfulness, which may represent both a technical and emotional problem for the practitioner. For two-thirds of physicians in the study, a conversation with a patient about dying and death was a problem. However, fewer palliative care physicians than internal medicine practitioners regarded such conversations as difficult. It is also less difficult for the respondents with a high level of determination of philosophy of life, and men. Interestingly, there was no such impact of religiousness, the age of respondents, or overall working years. It was also confirmed that fear of death results in the difficulty of having a conversation about dying and death. A clinician should pay more effort to his/her own philosophy of life, and consider/meditate on the issues of dying, the meaning of life, suffering, and death to be prepared for proper communication with the patient.

The problem declared by the majority (87%) of respondents was lack of skills of effective communication with the patient. Time consumption, moral doubts about providing such conversation, or the personal suffering caused by it appeared to be less important. Some respondents pointed out the communication with a patient’s family as a particular challenge. Physicians face a dilemma when families do not wish the patient to know about a cancer diagnosis, and this highlights the necessity of taking into consideration the social circumstances in healthcare [20].

Consistently, 69% of respondents expressed needs for training in communication skills (Q7.A). Three-fourths regarded mentoring by an experienced practitioner or training on communication with a patient as the most valuable means. This finding confirms the observation from other research on palliative care [21]. Around half of the physicians would expect a psychologist’s support as well. Not only did palliative care physicians appear more spiritually oriented than internal medicine practitioners, but also more often they expressed an interest in attending training programs on spirituality in medicine.

The results of this study differ in many aspects from one performed on the population of medical students shortly before graduation [12]. The young individuals, when entering adult life and approaching the physician’s profession, have their knowledge, skills, convictions, fears, prejudices, spirituality, and religious beliefs. Based on these internal resources the young professional acquires new experiences and develops skills of communication with the patient. According to Karger et al. (2015), longer and longitudinally integrated palliative care teaching may support an attitudinal change in a better way [22]. So, it was indicated in this study that the length of tenure in palliative care modifies the professional’s determination of philosophy of life and lowers the level of fear of death. Palliative care physicians acquire skills of breaking bad news to a higher degree than do internal medicine practitioners, and they recognise the importance of spirituality and try to foster it. Also, poor performance in breaking bad news may not only be an effect of lack of skills but also of burnout and fatigue [8]. Unlike burnout and fatigue, a personal value system is not a subject that undergoes prevention. However, this study highlighted that it might be modified by tenure and exposure to dying and death.

The limitation of the study is its synthetic short form. We decided to keep it as short as possible to focus on communication, and not on the fear itself. Consistently, we did not introduce scales of fear of death, such as the Lester Attitude Toward Death Scale or the Collett-Lester Fear of Death Scale [23, 24], because they have not been validated in the Polish language. They might have added some value regarding the elements of the fear.

There is also an issue in statistical comparison of the results of the studies performed in a group of students and experienced professionals, although it seems obvious that there should be post-graduation courses on communication skills for professionals of all specialisations, e.g. in students, the fear of death may affect the ability to break bad news to the patient and the will to know about one’s own impending death, while in this study there was no such impact found [12]. Such an investigation is planned as a separate study.

Another limitation of the study is the question (Q2) of a respondent’s own hypothetical death, which may be far from the truth in the case of a real threat of death. So, the answer to this question should be regarded as declared readiness to such information, and the results should be taken with caution.

In conclusion, personal fear of one’s own death may restrain inexperienced medical professionals from breaking bad news to patients. The level of determination of philosophy of life, but not religiousness, impacts the tendency to inform patients of upcoming death. Working in palliative care seems to augment determination of a philosophy of life. The higher the determination, the more positive the attitude to break bad news is. The specialisation and the length of the physician’s tenure have an impact on the level of the physician’s personal fear of death. Practitioners with longer working years and palliative care physicians tend to be less afraid of their own death. A longer tenure in palliative care makes breaking bad news less difficult than in internal medicine, although it always remains a significant problem. Mentoring by an experienced professional would be the most appreciated by the practitioners, as well as training sessions on communication with the patient and the support of a psychologist. Personal attitude should be addressed within the curriculum of physician-patient communication education.