Introduction

Alcoholic cirrhosis (AC) is a progressive liver disease characterized by fibrosis, which is caused by chronic liver injury. Most patients with cirrhosis remain asymptomatic, the prognosis being relatively good, and survival at 5 years can reach up to 90%, until they develop decompensated cirrhosis [1–3]. In this last stage, patients suffer complications associated with portal hypertension, including ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), hepatic encephalopathy (HE), hepatorenal syndrome, portopulmonary hypertension, or variceal bleeding [4–6].

Ascites results from portal hypertension, which causes water and sodium retention and the presence of excessive fluid in the peritoneum [7, 8]. For its part, encephalopathy is a neurological symptom caused by both parenchymal damage and portal hypertension, leading to an increase in ammonium levels, which would produce brain toxicity [9].

Survival rates for patients with cirrhosis substantially decrease once complications develop and, for this reason, patients with decompensated cirrhosis are generally indicated for liver transplantation (LT) [10]. Decompensated cirrhosis, with the subsequent development of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, has a significant impact on prognosis, with a survival rate of 85% in the first year and 56% at 5 years and only 50% at 10 years [11, 12]. In these cases, the main focus of pre-transplant management would be complete elimination of the main causes of cirrhosis such as alcohol consumption [13].

In recent years, the survival rate of liver recipients suffering AC has significantly improved, allowing this liver disease to be considered one of the best indications for LT. Nevertheless, patients should undergo a careful assessment of post-transplant risk considering rejection development, viral recurrence or alcoholic relapse [14–19].

Bearing all this in mind, it is important to indicate that in most cases when AC is in its terminal stages, LT is the most effective treatment to save life. Child-Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores have been widely used to predict the outcomes of cirrhotic patients with end-stage liver disease, but not specifically in AC patients. The Child-Pugh score includes ascites, HE, prothrombin time or international normalized ratio (INR), total bilirubin, and albumin. The MELD score incorporates only 3 objective variables: total bilirubin, creatinine and INR. A large number of studies have compared their discriminative abilities but the results remain controversial, some studies favoring the Child-Pugh score, and others the MELD score [14, 20–22].

Recently, Johnson and colleagues reported that the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score more accurately predicts patients’ mortality without requiring subjective determinants of liver failure, including ascites and encephalopathy, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma [23]. Other studies have evaluated the usefulness of the ALBI score in hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure and liver cirrhosis with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding [24–27].

The ALBI score only involves two common laboratory parameters, albumin and total bilirubin, and it has been used and validated in several studies associated with hepatocellular carcinoma patients in different tumor stages for assessing the severity of liver dysfunction [23].

Thus, the aim of this study was to analyze, in a large cohort of male AC patients undergoing LT with and without concomitant viral infections, the influence of ascites and/or encephalopathy in liver rejection development and post-transplant recipient survival to determine the usefulness of Child-Pugh, MELD and ALBI scores for the assessment of prognosis in AC patients.

Material and methods

Patient enrolment

The medical records of 281 AC recipients who had undergone LT were retrospectively studied at the University Clinic Hospital ‘Virgen de la Arrixaca’ in the province of Murcia (Spain) from 1990 to 2013.

Pediatric, re-transplanted, and combined transplant patients were excluded. Mean age immediately prior to transplant was similar (mean years ± SEM = 53.02 ±0.43 years) in all the analyzed patients. The clinical and biochemical characteristics of AC patients are shown in Table I.

Table I

Baseline demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of the male AC patients

| Parameter | Male alcoholic cirrhosis patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 281) | Non-viral n = 213 (75.8) | Viralb n = 68 (24.2) | |

| Agea | 53.06 ±0.45 | 55.14 ±0.54 | 48.9 ±0.94 |

| Ascites | 162/281 (78.3) | 119/281 (79.3) | 43/281 (75.4) |

| Encephalopathy | 91/281 (44.0) | 72/91 (47.1) | 19/91 (33.9) |

| Acute liver rejection | 59/222 (26.6) | 45/169 (26.6) | 14/53 (26.4) |

| Chronic liver rejection | 19/209 (9.1) | 17/158 (10.8) | 2 /51 (3.9) |

| Child-Pugh % (A/B/C) | 17.4/52.1/30.6 | 16.3/51.9/31.7 | 20.0/52.5/27.5 |

| MELD score | 14.3 ±0.4 | 14.6 ±0.4 | 13.5 ±0.8 |

| ALBI score | –1.93 ±0.05 | –1.98 ±0.06 | –1.82 ±0.10 |

| Biochemical parameters: | |||

| Creatinine [mg/dl] | 1.08 ±0.05 | 1.13 ±0.06 | 1.00 ±0.08 |

| Albumin [g/dl] | 3.46 ±0.05 | 3.51 ±0.06 | 3.31 ±0.09 |

| Total bilirubin [mg/dl] | 3.17 ±0.30 | 3.29 ±0.41 | 2.80 ±0.37 |

| GOT [U/l] | 95.72 ±13.34 | 92.95 ±19.54 | 108.40 ±14.29 |

| GPT [U/l] | 71.92 ±11.06 | 70.94 ±16.30 | 82.80 ±10.93 |

| GGT [U/l] | 99.92 ±6.78 | 95.73 ±7.90 | 122.61 ±15.87 |

| AP [U/l] | 173.60 ±8.52 | 157.74 ±9.29 | 218.60 ±19.86 |

| Prothrombin activity [%] | 58.93 ±0.94 | 58.52 ±2.00 | 58.91 ±2.10 |

| INR | 1.44 ±0.02 | 1.45 ±0.03 | 1.42 ±0.05 |

n – number of individuals with a particular disease, AC – alcoholic cirrhosis, MELD – model for end-stage liver disease, ALBI – albumin-bilirubin score, GOT – glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, GPT – glutamic pyruvic transaminase, AP – alkaline phosphatase, GGT – γ-glutamyl transferase, INR – international normalized ratio.

The inclusion criteria were primary LT without prior history of other organ transplants, ABO compatibility, HIV negativity, and whole liver allograft. A small cohort of AC women (n = 32) was also observed during the study period, but, due to the small sample size, they were excluded from this study. All patients gave informed consent to providing clinical information as well as follow-up data and the study protocol was approved by the institutional ethical committee study according to the Helsinki Declaration 2000.

Diagnostic criteria of alcohol cirrhosis and immunosuppression

Alcoholic cirrhosis was diagnosed using clinical, radiological, and biochemical parameters [28]. The opinion of relatives was taken into consideration in the case of a negative self-report of alcoholic beverage consumption. In most cases, there were no symptoms of cirrhosis in the first stage of the disease, so the diagnosis was made after a chance scan, ultrasound, or clinical examination. In other cases, the disease remained undetected until the second stage of decompensated cirrhosis, when complications such as ascites, upper gastrointestinal bleeding and encephalopathy appeared. Cases of suspected cirrhosis were confirmed using specific analysis and imaging technologies as previously reported [29]. It is important to note that the degree of hepatic fibrosis of all patients included in this study was grade F4 (METAVIR score), as ascertained using in most cases non-invasive procedures (FibroScan), at the time of inclusion on the waiting list for LT. All patients received standard triple-drug therapy as initial treatment with cyclosporine or tacrolimus, adjusted to maintain the recommended immunosuppressant levels.

Liver rejection diagnosis

Clinical, biochemical, and histological criteria, and the Banff scheme were used for acute (AR) and chronic (CR) liver rejections diagnosis and for grading liver rejection [30–32]. Episodes of rejection were treated with high-dose methylprednisolone (one bolus of 500 mg for 3 days).

Viral infection diagnosis and treatments

Hepatitis C (HCV) and hepatitis B (HBV) viral pre-infection was determined in all patients. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) pre-infection was determined using a qualitative immunoassay (AxSYM HCV v3.0; Abbott, Wiesbaden Delkenheim, Germany) to detect the presence of anti-HCV antibodies, and the results were confirmed by immunoblotting technology (recombinant immunoblot assay) or reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (REAL; Durviz, Valencia, Spain), following the manufacturer’s indications. Hepatitis B viral infection (HBV) was determined measuring the HBV surface antigen using a radioimmunological method (SorinBiomedica, Perugia, Italy). HCV-positive liver recipients were treated with pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) α-2b (PegIntron, Schering-Plough), and oral ribavirin (Rebetol, Schering-Plough). HBV-positive liver recipients were treated with anti-HBV γ-globulin (Grifols, Barcelona, Spain) and lamivudine (GlaxoWellcome, Triangle Park, NC). All patients were classified according to the presence (viral AC patients) or absence (non-viral AC patients) of concomitant viral infections.

Biochemical parameters analyzed in alcoholic cirrhosis patients

A total of nine biochemical parameters were analyzed (normal values between brackets): creatinine (0.7–1.2 mg/dl), albumin (3.5–5.2 g/dl), total bilirubin (0.3–1.9 mg/dl), alkaline phosphatase (AP; 40–130 U/I), glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT; 5–40 U/I), glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT; 5–41 U/I), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT; 10–71 U/I), prothrombin activity (70–100%) and international normalized ratio (INR; 0.9–1.2). Prothrombin activity was measured as percent of an internal reference standard (Normotest; Nycomed) and INR using standard formulae, considering three INR groups to calculate the MELD score.

Ascites and hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis

Pretransplant ascites was diagnosed, establishing 3 different grades ranging from low (grade I) to high involvement [6, 33]. Alcoholic encephalopathy pretransplant (HE) was diagnosed and classified into 4 different grades ranging from low (grade I) to high (grade IV) [34]. In some cases, no clinical notes regarding the presence or absence or degree of ascites or encephalopathy were found in the clinical history.

Child-Pugh and MELD scores

Liver function status in AC patients was evaluated by the Child-Pugh and MELD scoring systems; both scores were also used as a survival prediction model in patients with end-stage liver disease. For both score models, all analytical values of the patients on the waiting list for LT were obtained. The Child-Pugh scoring system classifies patients into 3 groups, A, B, and C, from low to high severity of damage [22]. The score was calculated from 5 variables: bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin, ascites status, and degree of encephalopathy [35].

The MELD score was calculated using a mathematical formula composed of serum creatinine, total bilirubin, and INR [21, 35]. MELD score = 3.78 × ln (total bilirubin µmol/l) + 11.2 × ln (INR) + 9.57 × ln (creatinine mg/dl) + 6.4 [36, 37]. Patients were classified according to MELD scores into 4 groups. High MELD values correspond to more severe liver damage but no case was observed in this study.

Albumin-bilirubin score

The albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score is a new model for assessing the severity of liver dysfunction and only involves two common laboratory parameters, albumin and total bilirubin.

The serum bilirubin and albumin values obtained before the procedure were used to calculate the ALBI grade using previously published criteria with linear prediction as follows: linear predictor = (log10 bilirubin × 0.66) + (albumin × –0.085), where bilirubin is in µmol/l and albumin is in g/l [23]. The ALBI score was used for grading (≤ –2.60 = grade 1, > –2.60 to ≤ –1.39 = grade 2, > –1.39 = grade 3).

Statistical analysis

The demographic data and results were collected in a database (Microsoft Access 2.0; Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA) and analyses were performed using SPSS v20.0 (SPSS software Inc.). All results were expressed as the mean ± SEM or as a percentage. Pearson’s χ2 and the 2-tailed Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorized variables between groups. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were also calculated. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to compare differences in short- and long-term AC patient survival. In all cases, a p-value below 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Influence of pretransplant ascites and hepatic encephalopathy on liver rejection

An overall percentage of AR of 26.6% was observed in the total AC patient group, while CR was only developed by 9.1% of all analyzed AC patients.

As shown in the top part of Table II, a percentage of AR of 18.5% was observed in all AC patients suffering ascites, and was similar in patients without ascites (15.6%, p = 0.826). An increase in the AR rate was observed in patients with grade III ascites (21.4%) but this difference was not significant compared with grade I (p = 1.000) or grade II (p = 0.496) ascites or with patients without ascites (p = 0.610).

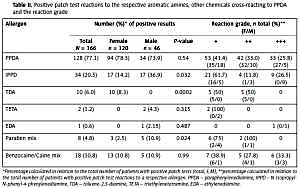

Table II

Analysis of acute and chronic liver rejection in male AC patients with pretransplant ascites or encephalopathy

| Pre-transplantation complications | Total AC patients, n (%) | Non-viral AC patients, n (%) | Viral AC patients*, n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute rejection | Chronic rejection | Acute rejection | Chronic rejection | Acute rejection | Chronic rejection | |||||

| Ascites, n = 207 | + | 162 (78.3) | 30 (18.5) | 10 (6.2) | 119 (79.3) | 24 (20.2) | 9 (7.6) | 43 (75.4) | 6 (14.0) | 1 (2.3) |

| – | 45 (21.7) | 7 (15.6) | 2 (4.4) | 31 (20.7) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.2) | 14 (24.6) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Grade | I | 32 (20.6) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (12.5) | 26 (22.4) | 3 (11.5) | 4 (15.4) | 6 (15.4) | 3 (50.0) | – |

| II | 67 (43.2) | 11 (16.5) | 3 (4.5) | 44 (37.9) | 9 (20.5) | 3 (6.8) | 23 (59.0) | 2 (8.7) | – | |

| III | 56 (36.1) | 12 (21.4) | 2 (3.6) | 46 (39.7) | 11 (23.9) | 2 (4.3) | 10 (25.6) | 1 (10) | – | |

| Encephalopathy, n = 207 | + | 91 (44.0) | 15 (16.5) | 5 (5.5) | 72 (47.1) | 12 (16.7) | 4 (5.6) | 19 (33.9) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (5.3) |

| – | 116 (56.0) | 21 (17.8) | 7 (5.9) | 81 (52.9) | 14 (17.3) | 6 (7.4) | 37 (66.1) | 7 (18.9) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Grade | I | 36 (41.9) | 4 (11.1) | 4 (11.1) | 27 (39.1) | 3 (11.1) | 4 (14.8) | 9 (52.9) | 1 (11.1) | – |

| II | 40 (46.5) | 11 (27.5) | – | 33 (47.8) | 9 (27.3) | – | 7 (41.2) | 2 (28.6) | – | |

| III | 10 (11.6) | – | – | 9 (13) | – | – | 1 (5.9) | – | – | |

A trend towards an increase in AR was observed in non-viral AC patients with different degrees of ascites, but this trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.445). A high AR value was observed in patients with grade III ascites (23.9%). Finally, the influence of ascites on the development of AR in viral AC patients was also evaluated, and no statistically significant differences were observed between patients with ascites and those without ascites (p = 0.229). Similarly, when patients with different ascites degrees were evaluated, no statistically significant differences were observed (p = 0.182).

On the other hand, CR was only developed by 6.2% of the total group of ascites AC patients, and there were no statistically significant differences from patients without ascites (4.4%, p = 1.000). This percentage was statistically similar in the different groups of ascites grades compared (p = 0.187). However, a slight increase in CR was observed in patients with grade I ascites (12.5%). Similar results were obtained when the study was conducted on non-viral AC patients (p = 0.232).

Finally, as shown in the lower part of Table II, AR in relation to the presence or absence of HE in AC patients was evaluated. The percentages of AR in the total group of HE patients and those without HE were similar (16.5% vs. 17.8%, p = 0.854) and similar trends were observed in non-viral and viral AC patients (p = 1.000, in both cases). In addition, the frequency of AR in the total group of HE patients (16.5%) was similar to that observed in the total group of ascites patients (18.5%, p = 0.735). A high percentage of AR was noted in the total group of patients with grade II encephalopathy (27.5%), regardless of the presence or absence of concomitant viral infections (28.6% and 27.3%, respectively).

With respect to CR, similar frequencies were observed between patients with and without HE (5.5% and 5.9%, p = 1.000, respectively), regardless of the presence or absence of concomitant viral infections. None of the patients experienced liver graft loss.

Post-transplant survival of alcoholic cirrhosis patients suffering pretransplant ascites or encephalopathy complications

Pretransplant ascites and encephalopathy were the main complications presented by our cohort of male AC patients. Ascites was observed in 78.3% of the total group of AC patients analyzed and was similarly represented regardless of the presence or absence of viral infections (75.4% and 79.3% respectively; p = 0.325, Table II). Post-transplant patient survival analysis at short and long term shows that ascites development in the patient does not significantly influence post-transplant survival, and the survival rates were similar between patients with ascites (77.2%) and without ascites (80%) 10 years after transplantation (p = 0.629, Figure 1 A).

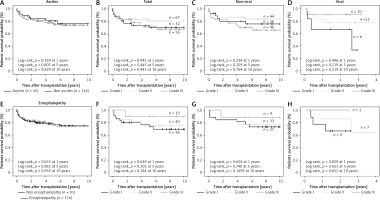

Figure 1

Kaplan-Meier patient survival curves of alcoholic cirrhosis patients with ascites or encephalopathy and concomitant viral infection. A–D – Kaplan-Meier patient survival curves of the total group of male alcoholic patients with ascites, and with and without associated viral infections. E–H – Kaplan-Meier patient survival curves of the total group of male alcoholic patients with encephalopathy, and with and without associated viral infections. Viral group included HCV and HBV

HCV – hepatitis C virus, HBV – hepatitis B virus, n – total number of patients included in each group considered.

On the other hand, encephalopathy was represented in 44% of the total group of AC patients and was similarly represented in non-viral and viral AC patients (47.1% and 33.9%, respectively; p = 0.457, Table II). Short and long term post-transplant patient survival showed that encephalopathy does not significantly influence post-transplant survival and for this reason the survival rates were similar between patients with HE (76.9%) and without HE (78%) at 10 years after transplantation (p = 0.935, Figure 1 E).

Post-transplant survival rates of alcoholic cirrhosis patients with different grades of ascites and/or hepatic encephalopathy pretransplant

For this analysis, AC patients were classified according to the degree of ascites into three groups. It was observed that most of the ascites patients had grade II–III (79.3%) and only 20.6% had grade I (Table II). Similar data were obtained for both AC patient groups with and without viral infection, except in the case of grade II ascites, which was more prevalent in viral than in non-viral AC patients (59% and 37.9%), differences that were statistically significant (p = 0.026, OR = 0.425, 95% CI: 0.203–0.891).

Analysis of short- and long-term patient survival shows that the degree of ascites suffered by patients does not seem to influence post-transplant survival either in the short or long term (p = 0.945 at 1 year and p = 0.445 at 5–10 years, respectively; Figure 1 B), or influence patient survival regardless of the presence or absence of viral infections, as can be seen in Figures 1 C, D.

When the different degrees of encephalopathy were analyzed, it was observed that most patients presented grade I and II (88.4%), and only 11.6% had grade III encephalopathy, the same being the case for both viral and non-viral AC patient groups (Table II). An analysis of patient survival showed that the degree of encephalopathy suffered by patients has no influence on post-transplant survival either in the short or long term (p = 0.639 at 1 year, p = 0.205 at 5 years and p = 0.184 at 10 years; Figure 1 F). Similar results were found in non-viral and viral AC patients (Figure 1 G, H).

Child-Pugh, MELD and ALBI scores for predicting survival in alcoholic cirrhosis patients with ascites and encephalopathy

Experimental and theoretical survival values were compared for both the Child-Pugh and MELD scoring systems (Table III). AC patients were classified according to their Child-Pugh, MELD and ALBI scores obtained while on the waiting list for LT. The presence of ascites, encephalopathy and concomitant viral infections was also considered in this study.

Table III

Comparison of experimental and theoretical survival rates according to Child-Pugh, MELD and ALBI scores in men AC patients

| Variable | Experimental survival rates (%) | Theorical survival rates (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC patients | AC patients with ascites | AC patients with encephalopaty | |||||||||

| Total | Non-viral | Viral | Total | Non-viral | Viral | Total | Non-viral | Viral | |||

| Survival at 2 years (%) | |||||||||||

| Child-Pugha | A | 92.0 | 94.1 | 87.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 91.4 | – | 100 | 85 |

| B | 79.7 | 79.2 | 81.0 | 76.3 | 75.6 | 77.8 | 83.3 | 87.0 | 71.4 | 57 | |

| C | 81.8 | 81.8 | 81.8 | 81.4 | 81.8 | 80.0 | 81.5 | 85.7 | 66.7 | 35 | |

| Survival at 3 months (%) | |||||||||||

| MELDb | < 9 | 85.7 | 92.3 | 75.0 | 88.9 | 100 | 80.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.1 |

| 10–19 | 93.0 | 92.1 | 96.2 | 92.5 | 92.1 | 94.1 | 95.2 | 97.1 | 87.5 | 94.0 | |

| 20–29 | 95.8 | 93.8 | 100 | 95.5 | 93.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 80.4 | |

| 30–39 | 100 | 100 | – | 100 | 100 | – | – | – | – | 47.4 | |

| Survival at 3 months (%) | |||||||||||

| ALBIc | 1 | 92.9 | 95.0 | 87.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| 2 | 94.0 | 95.8 | 89.7 | 93.1 | 96.1 | 85.7 | 95.2 | 97.1 | 87.5 | ||

| 3 | 87.9 | 81.8 | 100 | 88.9 | 81.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

*For both models, analytical values were obtained to get on the waiting list for liver transplantation.

a Child-Pugh score based on 5 variables including serum levels of bilirubin and albumin, prothrombin time, ascites, and encephalopathy (Pugh et al., 1973). Based on the values obtained, patients were classified into low (Class A), intermediate (Class B), and high risk (Class C).

It was observed that experimental survival values observed both in the short and long term in our patients, regardless of the presence of ascites, encephalopathy or associated viral infection, were higher than those theoretically proposed by both the Child-Pugh and MELD scores. In addition, no trend in survival was observed in any of the patient groups analyzed.

Finally, the post-transplant survival of patients was analyzed according to the ALBI model and classified into three groups. In the three ALBI groups analyzed, high survival rates were observed in all cases and no decreasing survival trend was observed, except in non-viral ascites patients, when it was observed that ALBI 3 (81.3%) patients had a slightly lower survival rate than ALBI 2 (96.1%) and ALBI 1 (100%) patients, but these trends were not statistically significant (p = 0.076).

Albumin-bilirubin and Child-Pugh score for predicting short- and long-term survival in alcoholic cirrhosis patients

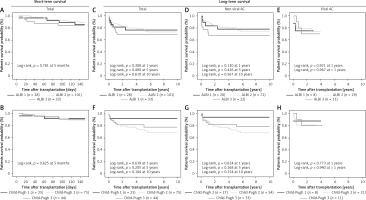

Short-term post-transplant patient survival was analyzed using ALBI and Child-Pugh scores and the patients were classified into three groups in both cases (Figures 2 A, B). The results showed no statistically significant difference in survival in any of the groups analyzed; nor was there any trend in mortality in the two proposed models (p = 0.781 and p = 0.825, respectively).

Figure 2

Kaplan-Meier patient survival curves of alcoholic cirrhosis patients according to ALBI and Child-Pugh scores. A, B) Kaplan-Meier patient short-term survival curves of the total group of male alcoholic patients according to ALBI (A) and Child-Pugh score (B). C–E) Kaplan-Meier patient long-term survival curves of the total group of patients and with and without associated viral infections according to ALBI score. F–H) Kaplan-Meier patient long-term survival curves of the total group of patients and with and without associated viral infections according to Child-Pugh score. Viral group included HCV and HBV

HCV – hepatitis C virus, HBV – hepatitis B virus, n – total number of patients included in each group considered

Subsequently, long-term survival over different time periods (1, 5 and 10 years) was also analyzed using the ALBI score (Figures 2 C–E). No statistically significant differences in survival frequency were observed for any of the time periods analyzed. No difference was also observed when patients were classified according to the presence or absence of viral infections.

Finally, long-term patient survival was also analyzed using the Child-Pugh score (Figures 2 F–H). Similarly, no statistically significant differential trend in survival was observed in any of the three Child-Pugh groups analyzed. In both models the scores showed no difference in patient survival from 6 years after the transplant.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, the influence of pre-transplant clinical complications (ascites and/or encephalopathy) was studied in a large cohort of male AC patients, with and without concomitant viral infections, to predict the outcome of liver transplantation and to determine the usefulness of the Child-Pugh, MELD or ALBI scores in the prognosis.

Despite clinical improvements in the post-transplant survival of AC patients, liver graft rejection, viral recurrence or alcoholic relapse remain important post-transplantation risks to which the patient is exposed [14–16, 38, 39]. In our series of AC patients, the most common pre-transplant complication found was ascites (78.3%), predominantly grade II and III, regardless of concomitant viral infections. This percentage is high compared with the findings of other studies that determined that ascites usually develops within 10 years during the course of disease in 60% of patients with compensated cirrhosis [8, 40, 41].

Encephalopathy, mainly grade I and II, was found in almost half of our patients. Both pre-transplant complications are considered in the Child-Pugh score to classify patients by severity and to predict patient survival. Treatments and protocols for the patient with ascites and/or encephalopathy have improved substantially [42, 43], so it is necessary to rethink its usefulness for assessing the patient.

On the one hand, our data show that liver graft rejection rates in AC patients were slightly higher, but not significantly so, than the mean values obtained from patients with other liver transplantation indications [29]. Our results show that ascites and encephalopathy do not appear to have a significant influence on acute or chronic liver graft rejection in AC patients. However, a higher AR percentage was observed for patients in advanced stages of both ascites (grade III) and encephalopathy (grade II), and an increase in CR was observed in AC patients with stage I ascites or encephalopathy regardless of viral infection. Indeed, several studies have been performed to identify biomarkers of rejection or tolerance in liver transplant patients; most of them were based on the analysis of peripheral blood samples and transcriptional profiling techniques [44].

Ascites and particularly encephalopathy in the setting of chronic liver disease are traditionally thought to be poor prognostic markers of end-stage liver disease. Several studies have indicated that ascites is an indicator with a mortality rate of approximately 40% after 1 year and 50% within 2 years [40, 41, 45]. In addition, refractory ascites, defined as ascites resistant to medical therapy [46], develops in < 20% of patients with ascites and is associated with a high 1-year mortality rate (∼50%) [47]. It should be noted that all these studies were conducted in cases involving different liver diseases but none of them analyzed the influence of ascites or encephalopathy in AC patients.

In all cases, the survival of our AC patients with grade II–III ascites and classified into low (class A) or intermediate (class B) by the Child-Pugh score was higher than expected at 1 year (85.8%) and 5 years (70%) after the transplant [22]. These same trends in patient survival were also observed in non-viral AC patients. However, viral AC patients with grade II ascites seem to present a greater chance of survival than patients with grade-I ascites, although perhaps this could be related to the small sample size analyzed in our series; whatever the case, these differences were not statistically significant.

For its part, HE affects approximately 20% of patients suffering liver cirrhosis each year, affecting their quality of life [48], and serves as a poor prognostic indicator for such patients, with a survival of only 23% at 3 years from onset [49]. Treatments aimed at interrupting the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy are known to improve survival [50]. Our study shows that AC patients suffering HE pre-transplant, regardless of the presence or not of viral infection, do not show any differences in short- and long-term survival. Whatever the case, liver transplantation is beneficial for these AC patients as their survival is considerably increased. Stewart et al. [51] found a 3.9-fold increase in mortality among 271 patients hospitalized with hepatic decompensation and HE grade 2 or higher. For these reasons, clinicians need to be able to recognize signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy in patients who might not have a diagnosis of chronic liver disease [52].

Finally, when comparing the experimental survival values observed in both short-term and long-term survival in our AC patients, regardless of the presence of ascites, encephalopathy or viral infection, it was observed that the theoretical values proposed by Child-Pugh and MELD scores showed survival rates that do not reflect the experimental rates. In our patient series, the MELD score fitted the experimental values best. However, in a similar study on patients with cirrhosis due to hepatitis B virus infection, other authors compared the performance of the Child-Pugh with that of the MELD score for predicting survival and observed that the scored had the same prognostic significance [53].

Recently, the ALBI score has been used in patients with hepatocarcinoma for assessing the severity of liver dysfunction [23]. In that, study, the ALBI score was positively correlated with the MELD score and the Child-Pugh score. Moreover, ALBI scores were higher among non-survivors than survivors in hepatocarcinoma patients. However, no studies have evaluated the ALBI score in AC patients in the terminal stages of their disease. Our results show no significant relationship between short- or long-term survival values and the different ALBI grades. Perhaps this is because the pre-transplantation albumin values were within the normal range, while the bilirubin values were very high in our patients who were on the waiting list to receive a liver transplant. After liver transplant, the hepatic dysfunction disappeared.

However, Chen et al. [54] demonstrated that the ALBI score performed significantly better in terms of long-term survival prediction in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis than the Child-Pugh or MELD scores. In our study, due to the small cohort of patients with viral infections it is not possible to correctly assess the usefulness of the ALBI score, although our preliminary data do not show any statistically significant trend in survival rates.

In conclusion, the results from the present study show that the pre-transplant complications ascites and encephalopathy do not appear to influence short- and long-term patient survival or acute and chronic liver rejection in AC patients with or without an associated viral infection. The Child-Pugh and MELD scores for the assessment of prognosis in alcoholic liver cirrhosis had a similar experimental prognostic value in most cases, although the experimental Child-Pugh score differed most from the theoretical values. Similarly, the ALBI score did not seem to be very useful in patients in advanced stages of their disease and undergoing LT. In view of our results, new biomarkers and scores should also be studied to more accurately assess the prognosis of patients with alcoholic liver disease in advanced stages of cirrhosis.