Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive, irreversible, and usually fatal disease. It is characterized by excessive accumulation of collagen in extracellular matrix (ECM) of the lungs. The lung architecture is progressively remodeled by deposition of collagen proteins, leading to respiratory failure with a median survival of less than three years [1–3]. Although the precise mechanisms underlying the development of IPF still remained to be elucidated, excessive collagen accumulation of ECM has been suggested to play an important role in fibrotic processes [4]. Collagen synthesis is a multi-step process that involves post-translational modifications essential for stabilization of the collagen molecule. The assembly of collagen molecules into their functional units, collagen fibrils, is stabilized by covalent intermolecular cross-links [5, 6].

Lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3) is a collagen cross-linking enzyme, a member of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase family. It is encoded by procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 3 (PLOD3) [7]. However, lysyl hydroxylase 3 modifies cross-linking proteins by converting lysine to hydroxylysine, which makes collagen more resistant to degradation [6, 8]. The hydroxylation of lysine residues is a key step in the maturation of collagen because they determine the chemical nature of the intermolecular cross-links [9]. Lysyl hydroxylase 3 is still under investigation. It catalyzes the formation of hydroxylysyl residues in collagens and other helical proteins with collagenous domains, and therefore fulfills an important role in collagen post-translational modification and hydroxyallysine cross-linking formation [10].

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a necessary molecular information transmission system for the development of lung tissue. Abnormalities of its expression are closely related to chronic respiratory diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis and lung tumors [11–13]. iCRT3 is a small molecule inhibitor of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Its inhibition is achieved through blocking β-catenin nuclear transfer, inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling transduction [14, 15]. TGF-β acts as a key factor whose activation has been implicated in both pulmonary fibrosis (PF) and airway remodeling in this process [16]. Smads family proteins play a key role in the process of transducing receptor-ligated TGF-β signals to the nucleus, and the signal transduction is mediated by different members of Smad and TGF-β families [17]. Although it appears that epithelial cell activation of TGF-β by Smads is central in pulmonary fibrosis (PF), mesenchymal activation of TGF-β by Smads still remains controversial [18]. Whereas there is evidence for cross-talk between these two pathways in the context of development and tumorigenesis, the effects of these interactions in non-transformed adult cells are not well defined [19, 20]. Precise targets and mechanisms concerning the divergent functional outcome of the two pathways’ interactions in many cases remain unknown.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of the gene and protein expression of PLOD3/LH3 on pulmonary fibrosis, to examine whether LH3 has a potential effect on hydroxyallysine cross-linking formation, and explore the mechanisms through which LH3 was activated by TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling through Wnt/β-catenin and characterize its role in lung fibrosis. Understanding the mechanism on the basis of stabilized collagen synthesis and the cross-talk between the two signal pathways may provide useful strategies for preventing or treating pulmonary fibrosis.

Material and methods

Cell line and culture

Human lung cancer cell line A549 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, CA, USA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells in each group were seeded in 25 cm2 culture flasks for 24 h or 48 h for further study.

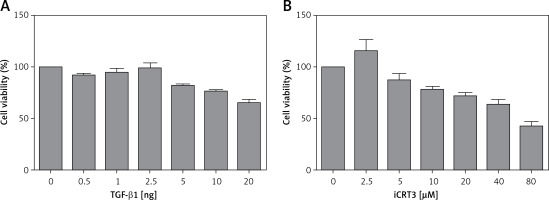

MTT assay

A549 cells were digested and counted for preparing the cell suspension. We seeded 200 µl of cell suspension onto 96-well plates with 5 × 103 cells per well; when the cells reached 70–80% confluence they were cultured in DMEM medium without FBS for 6 h before being stimulated with 0 ng, 0.5 ng, 1.0 ng, 2.5 ng, 5 ng, 10 ng and 20 ng of recombinant human TGF-β1 (100-21C; PeproTech, Princeton, USA) or 0.1% DMSO (AMRESCO, USA) was added in the amounts 0 µM, 2.5 µM, 5 µM, 10 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM and 80 µM iCRT3 (MCE, USA) was added in the experimental group. Then, the cells were cultured in a CO2 incubator, and we assessed cell viability once after 24 h. Before detection, 20 µl of methylthiazolydiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution (Beyotime, China) was added into each well and incubation was continued at 37°C for 4 h. Then, the culture medium was discarded, DMSO was added into each well at room temperature, and it was shaken for 10 min. The OD value was measured with a microplate reader in 490-nm excitation light. Finally, the multiplication curve was plotted.

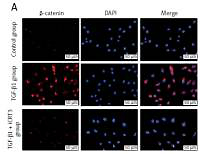

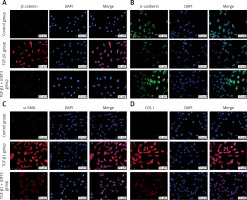

Immunofluorescence staining

A549 cells were digested by trypsinization and pooled in complete DMEM medium. Then they were counted for preparing the cell suspension. We seeded 200 µl of cell suspension onto 6-well plates with 5 × 104 cells per well; after the cells’ adherence, the medium was discarded and replaced with 4 ml of medium containing TGF-β1 or TGF-β1 + iCRT3 for each group, respectively, and incubation was continued at 37°C for 48 h. Cells were washed with PBS for 5 min. Thereafter, 0.5% Triton X-100 was used to permeabilize the cell membrane for 30 min. The cells were subsequently incubated with anti-β-catenin (1 : 100, Abcam, ab32572), anti-E-cadherin (1 : 100, Santa Cruz, sc-56527), anti-α-SMA antibody (α-SMA, 1 : 100, Abcam, ab7817) or anti-collagen I antibody (COLI, 1 : 100, Abcam, ab6308) overnight at 4°C (12–16 h), followed by incubation with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies and counterstaining with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Finally, the pictures on the slides were captured using a Leica confocal microscope (Leica DM400B, Germany).

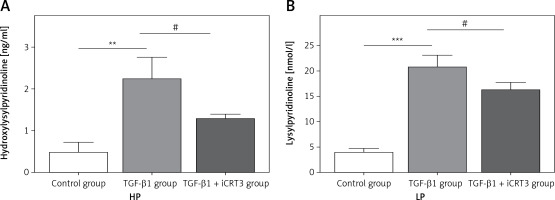

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The protein expression levels of lysylpyridinoline (LP) and hydroxylysylpyridinoline (HP) in the lung cells were detected using commercial ELISA kits (Jianglai, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After the reaction, the optical density was measured at 450 nm using a plate reader (ELX-800, BIOTEK, USA). The HP levels were expressed as ng/ml of lung cells and the LP levels were expressed as nmol/l of lung cells.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the A549 cells using the Trizol reagent (Thermo, USA). The RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using reverse transcription kits (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) and the cDNA was subjected to RT-qPCR amplification. The RT-qPCR amplification of cDNA sequences was performed for PLOD3, collagen I (COLIA1) (additional molecules involved in fibrosis). Each cDNA was amplified using the specific primers shown in Table I in a total reaction volume of 20 µl containing 10 μl 2× SuperReal PreMix Plus, 2 μl cDNA, 500 nM each primer, and 6 μl RNase-free ddH2O. PCR was performed in a Bio-Rad sequence detection system and consisted of a 15-min interval at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 58°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Data were analyzed using the Sequence Detector version 1.7 software (Table II).

Table I

Cell groups with different transfected plasmids

Table II

Sequences of primers for quantitative real-time PCR

Western blot analysis

After harvesting, A549 cells were washed twice with PBS, and homogenates were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime P0013B, China) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (both from KangChen, Shanghai, China). The protein concentration was determined using BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kits (Beyotime P0012, China). The protein samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were then blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS-T for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with anti-β-actin (1 : 4000, Lianke China, ab008-100), anti-α-SMA (1 : 300, Abcam, ab7817), anti-collagen I (1 : 500, Abcam, ab6308), anti-collagen IV (1 : 500, Santa Cruz, sc-59772), anti-Smad3 (1 : 500, Santa Cruz, sc-4709), anti-p-Smad3 (1 : 500, Santa Cruz, sc-517575), anti-Wnt1(1 : 1000, Abcam, ab15251), anti-β-catenin (1 : 1000, Abcam, ab32572) and anti-PLOD3 (LH3, 1 : 500, Abcam, ab128698) antibodies overnight at 4°C (12–16 h).

The secondary antibody used for the anti-Wnt1, anti-β-catenin and anti-PLOD3 antibodies was goat-anti-rabbit HRP (1 : 5000) (Boshide, Wuhan, China). The secondary antibody used for the anti-β-actin, anti-α-SMA, anti-collagen I and anti-collagen IV antibodies was goat-anti-mouse HRP (1 : 5000) (Boshide, Wuhan, China). The reaction was developed using ECL reagents (Clarity Western ECL Substrate, Bio-Rad, 170-5061) plus a Western blot detection system (ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System, Bio-Rad, USA). Quantification of the Western blot signals was performed by measuring the intensity of the specific bands using the Quantity One v. 4.6 image analysis program. Protein expression levels were calculated after normalizing their expression to that of β-actin.

PLOD3 plasmid transfection

A549 cells were first transfected with endogenous PLOD3-shRNA targeting the human PLOD3 gene or pCMVGFPPuro05-PLOD3 targeting the human PLOD3 gene or negative control non-targeting plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The PLOD3-shRNA, pCMVGFPPuro05-PLOD3 and negative control plasmids were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China) according to human-specific sequences, which were transfected into A549 with Lipofectamine 3000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To identify whether the gene was silenced or overexpressed completely, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed. After 6 h, medium was replaced with fresh medium supplemented with or without TGF-β1 for an additional 48 h. Results were presented as relative mRNA levels normalized against those of GAPDH. Proteins were harvested for detection by Western blot analysis (Tables I, III, IV).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. The values are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD), and the significance of differences between means was calculated with a one-way ANOVA followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test using the SPSS 17.0 software (IBM, New York, NY, USA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Effect of TGF-β1 or iCRT3 on A549 cell growth activity

The results of the MTT assay showed that the relative activity of A549 cells started to decrease when they were treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β1, indicating that this concentration of TGF-β1 could inhibit the growth viability of A549 cells. But according to the literature, when cell growth activity is inhibited by 25–30%, this concentration is used for subsequent experiments. Therefore through comprehensive analysis, the dose of 10 ng/ml was used in pulmonary fibrosis induction with TGF-β1 in vitro. Similarly, we selected 5 µmol/l iCRT3 for intervention with A549 cells (Figure 1).

TGF-β1 activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling transduction and epithelial mesenchymal transition to induce fibrosis marker protein expression

Because of the crucial role of TGF-β1 in fibrotic disease, we speculated that TGF-β1 signaling might contribute to activation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Stimulation with TGF-β1 did induce nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in cultured A549 cells. Under normal conditions with β-catenin COLI and α-SMA expression was hardly detected by immunofluorescence staining, but E-cadherin was highly expressed. After TGF-β1 stimulation, β-catenin (red fluorescence), α-SMA (red fluorescence), COL I (red fluorescence) protein presented high expression in the cytoplasm, and E-cadherin (green fluorescence) protein expression decreased. However, applying iCRT3 intervention, β-catenin, COL I and α-SMA expression was significantly decreased in the cytoplasm, and E-cadherin expression increased (Figure 2).

Expression levels of lysylpyridinoline and hydroxylysylpyridinoline in A549 cells

Having established that TGF-β1 could induce expression of collagen, it remained to be explored whether increase of collagen synthesis related to collagen pyridine-crosslinking increased. ELISA results suggested that the contents of HP and LP were significantly increased in the TGF-β1-induced A549 cells. However, following iCRT3 treatment, the contents of HP and LP were decreased (Figure 3).

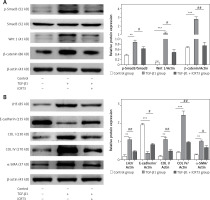

iCRT3 treatment blocked TGF-β1-induced TGF-β1/Smad3 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling transduction and inhibited pulmonary fibrosis

Next we examined the effects of iCRT3, to investigate whether the TGF-β1/Smad3 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways were related to the TGF-β1-induced pulmonary fibrosis in vitro, and whether iCRT3 could block these pathways and decrease LH3 and collagen expression. The A549 cells with TGF-β1-induced lung fibrosis showed high levels of Wnt1,β-catenin and p-Smad3 protein expression (Figure 4 A). To further examine the effects of iCRT3 treatment on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers such as α-SMA, we next explored possible mechanisms underlying the TGF-β1-induced human pulmonary epithelial cell line A549. We detected the E-cadherin, α-SMA, collagen I, collagen IV and LH3 protein expression by western blot. The results showed that α-SMA, collagen I, collagen IV and LH3 protein expression significantly increased in the TGF-β1 group, but E-cadherin expression decreased. These increases in protein expression were largely abrogated by iCRT3 treatment. However, E-cadherin protein was restored (Figure 4 B).

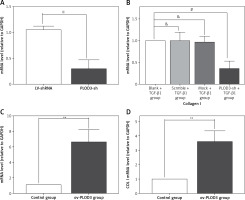

Knockdown of PLOD3 antagonized TGF-β1-induced fibrous marker gene and protein expression

RT-qPCR results revealed that the expression of COLI mRNA was down-regulated after knockdown PLOD3. However, ov-PLOD3 up-regulated the expression level of COL I mRNA (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Expression of PLOD3 mRNA and COL I mRNA. A – PLOD3 mRNA level of knockdown PLOD3. B – Collagen I mRNA level of knockdown PLOD3. C – PLOD3 mRNA level of overexpression PLOD3. D – Collagen I (COL I) mRNA level of overexpression PLOD3

Values are given as the means ± SD, n = 3; &p > 0.05 vs. Blank + TGF-β1 group; #p < 0.05 vs. TGF-β1 + BLM group; ※p < 0.05 vs. LV-shRNA; **p < 0.01 vs. control group.

Western blot results showed that the expression of fibrous marker proteins was increased in the TGF-β1 group; such markers included COLI and COLIV proteins. However, changes in expression of these proteins were substantially decreased in the knockdown PLOD3 (Figures 6 A, B). However, overexpression PLOD3 led to a significant increase of COLI and COLIV proteins (Figures 6 C, D).

Figure 6

Expression of PLOD3, COL I and COL IV protein. A – PLOD3 protein level of knockdown PLOD3. B – Expression of COL I and COL IV protein of knockdown PLOD3. C – PLOD3 mRNA level of overexpression PLOD3. D – Expression of COL I and COL IV protein of overexpression PLOD3. Relative expression levels of the cell samples were normalized to the expression of β-actin (actin)

Values are given as the means ± SD, n = 3;&p > 0.05 vs. blank + TGF-β1 group; ※※p < 0.01 vs. LV-shRNA group; #p < 0.05 vs. blank + TGF-β1 group; *p < 0.05 vs. control group,**p < 0.01 vs. control group.

Discussion

Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway seems to be a general feature of fibrotic diseases that occurs in systemic fibrotic diseases such as systemic scleroderma (SSc), but also in isolated organ fibrosis such as pulmonary fibrosis [21]. Indeed, pathologically activated canonical Wnt signaling has been implicated in various fibrotic diseases [22–27]. The activation of the canonical Wnt pathway has a key role for epithelial mesenchymal transformation (EMT) and collagen release in fibrosis. TGF-β1 stimulated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, increased the release of extracellular matrix components and induced fibrosis. The activation of the canonical Wnt pathway and its potent profibrotic effects suggest that the Wnt pathway might be a potential target for novel antifibrotic approaches. Of particular interest, our data highlight the cross-talk between TGF-β signaling and the canonical Wnt pathway [21]. We demonstrated at multiple experimental levels that TGF-β activates the canonical Wnt pathway. TGF-β seems to be the major stimulus for the activation of the canonical Wnt pathway in fibrotic diseases, because inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway transduction by a selective iCRT3 inhibitor strongly reduced the expression of p-Smad3, Wnt1, β-catenin, LH3 and fibrous marker protein.

Here we have demonstrated that LH3 represented a target to increase stabilized collagen synthesis. Its activity is regulated by TGFβ1/Smad3 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. IPF is caused by excessive deposition of collagen in ECM, which is due to an imbalance between collagen synthesis and degradation [28]. This accumulated collagen in fibrotic lesions shows an increase in hydroxyallysine-derived cross-links, which most likely contributes to the unwanted accumulation by conferring increased resistance to proteolytic degradation [29]. Moreover, disruption of the pyridine cross-linking formation affects collagen synthesis of ECM and decreases fibrotic lesions.

It was previously discovered that iCRT3 blocks signaling transduction of Wnt/β-catenin and TGFβ1/Smad3 [14, 15], thus inhibiting downstream lysyl hydroxylase 3 gene and protein expression. It was postulated that iCRT3 might possess anti-fibrotic properties by reducing the total number of lysine pyridinoline cross-links and hydroxyallysine pyridinoline cross-linking formation. However, the ability of iCRT3 through blocking Wnt/β-catenin signaling transduction to prevent pulmonary fibrosis, and the mechanism(s) underlying the anti-fibrotic effects, have been unclear. In the present study, we found that the expression of the individual LH3 and fibrosis-related molecules related to the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The present study was undertaken to obtain a better understanding of the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis.

Although treatment with iCRT3 repressed the expression of the PLOD3 gene, it appeared to have the most profound effect on the expression of PLOD3/LH3. LH3 is the only enzyme capable of glucosylating the galactosylhydroxylysine residues in proteins with a collagenous domain [30]. Our data revealed that iCRT3 treatment reduced both pyridinoline cross-links (LP and HP) and the total collagen fibril biosynthesis. However, the number of LP cross-links formed was much higher than expected based on the effects of lysyl hydroxylation, suggesting that LH3 preferentially hydroxylates lysine residues at the cross-linking positions. For further studies, it is warranted to investigate whether LH3 has a leading role in collagen post-translational modifications and the stable formation of collagen during TGF-β1-induced pulmonary fibrosis. In further research by knockdown of PLOD3 or using iCRT3, we will investigate whether it can prevent pulmonary fibrosis in vivo.

Our data also indicated that the effects of LH3 were at least partly mediated via the TGF-β1/Smads and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. In conclusion, we believe that both pathways play an important role in collagen cross-link formation, and there is complicated cross-talk between the two pathways. If the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is blocked, the TGF-β1/Smads pathway would be blocked too, and the expression level of the LH3 gene and protein would decline. Thus, to completely inhibit the process of lung fibrosis, blocking the EMT process alone is not enough. Therefore, although the present data show that TGF-β1 directly induced the phosphorylation of Smad3, the mechanism underlying TGF-β1-activated phosphorylation of Smad3 is still unresolved. Additional studies, therefore, are needed to determine how iCRT3 exerts its effects on the Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β1/Smads signaling pathways, and to confirm whether the potential target can be used therapeutically for pulmonary fibrosis. Thus it needs further studies to support the above points.

In conclusion, our present results showed that there is increased LH3 expression in TGF-β1-induced lung fibrosis in vitro. LH3 activity is regulated by Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathways. iCRT3 could prevent two signaling pathways’ transduction and reduce lung fibrosis, which also down-regulated the expression of the PLOD3/LH3 gene and protein to decrease the synthesis of lysylpyridinoline cross-linking and hydroxylysylpyridinoline cross-linking. This reduction in turn led to a decrease in collagen biosynthesis, then prevented EMT. Thus our results suggested that it may be a useful therapeutic or preventive agent for pulmonary fibrosis.