Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide with the common cancer type [1, 2]. Excessive proliferation of cells causes the initiation and progression of malignant tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma [3–5]. The prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma featuring high postoperative recurrence and probability of metastasis is still not satisfactory due to the lack of available treatments [6–8]. Furthermore, the latent molecular mechanism by which HCC progresses and metastasizes is still unclear. Therefore, it is urgent to elucidate the mechanisms whereby suppressing proliferation and enhancing apoptosis may provide new targets for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy.

The long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which do not contain any open reading frame with more than 200 nucleotides in length, are gradually being proven to be associated with diverse bioprocesses and diseases in humans [9]. In recent years, the association between lncRNAs and cancer development has attracted the eyes of many researchers [10]. Many lncRNAs have been reported as tumor regulators in various types of carcinomas such as breast cancer [11, 12], kidney cancer [13], lung cancer [14], etc. Also, it is reported that some lncRNAs play a key role in development and progression of HCC [15–18].

Recently, lncRNA has been identified as a sponge for mediating miRNA expression and named as a competitive endogenous RNA [7, 8, 19, 20]. Growing evidence has revealed that ectopically expressed lncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 (SNHG1) could function as an oncogene to enhance cell proliferation, migration and invasion in several cancers, such as non-small cell lung cancer [14] and prostate cancer [21]. However, the mechanism of SNHG1’s effect on hepatocellular carcinoma has not been elucidated. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that SNHG1 acts as an important regulator of the regulation of progression of various cancers by sponging to miR-195 and miR-199a-3p [22].

Now, we investigated the influence of SNHG1 on cell migration and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma and its relationship with miR-195. The present study may provide deeper understanding of SNHG1-miR-195 in HCC and a new potential target for the treatment of HCC.

Material and methods

Tissue specimens

In total, 60 matched hepatocellular carcinoma specimens of patients with pathological diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and corresponding adjacent non-tumor tissues were recruited from the Clinical Laboratory of Hainan General Hospital between October 2015 and September 2017. Immediately after the surgery, all tissue samples from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were treated in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at –80°C until use. Clinical characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma included in the present study are presented in Table I. The medical ethics committee of Hainan General Hospital approved this research. A letter of written agreement consistent with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration was obtained from each participant before the study.

Table I

Clinical characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma included in the present study (n = 60)

Cell culture and transfection

Cells from the hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines Huh7 and HepG2 and the immortalized human fetal liver cell line L02 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Briefly, cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% Gibco fetal bovine serum (FBS) (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, Ut, USA) under 37°C with 5% CO2. The HCC cells were transfected with SNHG1si-RNA, si-Negative Control (si-NC) or si-SNHG1 combined with miR-195 inhibitor (10 nmol/l for each) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Si-RNA of SNHG1 was synthesized by Guangzhou ribobio Co. Ltd. China with the sequence of si-5′-CUUAAAGUGUUAGCAGACATT-3′. miR-195 inhibitor was purchased from Shanghai Gene Pharma Co., Ltd, China with the sequence of 5′-GCCAAUAUUUCUGUGCUGCUA-3′. The negative control was a blank vector while the control group was without any treatment.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated with the TRIzol (Invitrogen, America) reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 1 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed using the Reverse EasyScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Trangene, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using the SYBR Green Master Mixture (Roche, America) reagent in an ABI 7500 Real-time PCR instrument. The following primers were used to detect the expression: the stem-loop RT primer for miR-195, 5′-GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACGCCAAT-3′ and the amplifying primers for miR-195, forward 5′-CGTAGCAGCACAGAAAT-3′ and reverse 5′-GTG CAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; SNHG1, forward 5′-AGGCTGAAGTTACAGGTC-3′ and reverse 5′-TTGGCTCCCAGTGTCTTA-3′; Astrocyte elevated gene 1 (AEG-1), forward 5′-AAATGGGCGGACTGTTGAAGT-3′ and reverse 5′-CTGTTTTGCACTGCTTTAGCAT-3′; GAPDH, forward 5′-AAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCA-3′ and reverse 5′-GGAAGATGGTGATGGGATTT-3′. The relative expression level of miRNAs was normalized to U6 small nucleolar RNA. All qRT-PCR runs were repeated in three replications. The results were calculated with the 2–ΔΔCt method. GAPDH served as an internal control.

MTT assay

After 48 h after transfection, the effect of lncRNA SNHG1 on the proliferation of Huh7 and HepG2 cells was measured by MTT assay. The cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 96-well plates and transfected with 50 nM Ln cRNA mimics. 1 × 104 cells per well were cultured in 96-well plates. MTT (100 μl) was added and incubated for an additional 4 h. Next, 150 μl of DMSO was added and the absorbance was read at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific).

Cell migration and invasion test

For the migration assay, 1 × 105 Huh7 and HepG2 cells were seeded in six-well plates and cultured at 37°C. A linear wound was carefully made in the middle of the plates, and cell debris was removed and incubated with serum-free medium. The wounded monolayers were then photographed at 0 and 24 h after wounding. For the invasion assay, 3 × 105 cells were seeded in FBS-free DMEM in 24-well transwell chambers pre-coated with Matrigel (BD Bioscience, USA). The lower chamber was filled with DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS. After 24 h of incubation, cells in the upper chamber were removed, and the cells that had traversed the membrane were stained with crystal violet. All experiments were performed at least three times in triplicate.

Western blotting analysis

Briefly, total protein extracted from cells was quantified with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Inc.), then loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight, and subsequently incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies at 37°C for 45 min. The target bands were scanned using Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GAPDH served as an internal control.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

The miR-195 full length 5′ lncRNA SNHG1-binding seed region or mutant (Mut) was amplified and sub-cloned into the pGL3-basic luciferase vector (Promega, USA). Huh7 and HepG2 were co-transfected with either the wild-type or Mut SNHG1-binding seed region, together with lncRNA SNHG1 or pcDNA6.2-control. After 48 h of transfection, relative luciferase value was measured and normalized to the values of Renilla luciferase activity using the Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Cat. E2610, Promega).

Results

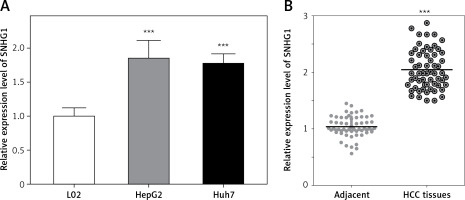

Long non-coding RNA SNHG1 was up-regulated in HCC cell lines and tissues

The expression level of SNHG1 was detected in two hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines, Huh7 and HepG2. Generally, a significant increase in SNHG1 expression was observed in cancer cell lines compared to normal liver cell lines (Figure 1 A, p < 0.001). Additionally, the levels of SNHG1 expression were detected in 60 paired hepatocellular carcinoma tissues and normal adjacent liver tissue. Consistent with this observation, SNHG1 was significantly up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues in comparison to the levels in adjacent non-tumor tissues (Figure 1 B, p < 0.001). These results indicated that SNHG1 expression was impaired in HCC and may be involved in HCC progression.

Figure 1

Long non-coding RNA SNHG1 was up-regulated in HCC tissues and cell lines. A – Expression of SNHG1 in cell lines HepG2 and Huh7, and a normal human hepatic cell line (L02); ***p < 0.001 vs. control. B – The levels of SNHG1 were quantified by qRT-PCR analysis in tumor tissues and normal tissues (n = 60)

Knockdown of SNHG1 inhibits HCC cell proliferation and induces apoptosis

To determine the function of SNHG1 in hepatocellular carcinoma tumor genesis, Huh7 and HepG2 were transfected with si-SNHG1 and the scramble negative control si-Scramble. The results showed that compared with si-Scramble, the levels of SNHG1 in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected with si-SNHG1 were significantly down-regulated (Figure 2 A, p < 0.01). We then performed an MTT assay to determine cell proliferation, and as a result, knockdown of SNHG1 was scrambled by the negative control (p < 0.05) (Figures 2 B, C) compared to the control group. As shown in Figures 2 D and E, inhibition of SNHG1 expression reduced the invasive ability of Huh7 and HepG2 cells (all p < 0.01). These results indicate that inhibition of si-SNHG1 can significantly inhibit migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

Figure 2

Silencing SNHG1 could significantly inhibit migration and invasion of HCC cells. A – The interfering effects of si-SNHG1 were evaluated in Huh7 and HepG2 cells after transfection with si-SNHG1 or si-Scramble; B, C – the Huh7 and HepG2 cells were transfected with si-SNHG1 or si-Scramble and the MTT assay was used to detect the cell proliferation; D, E – results of transwell assay in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected with si-RNA and si-NC. The invasion of HCC cells was significantly inhibited by si-SNHG1

*P < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared with the si-Scramble group.

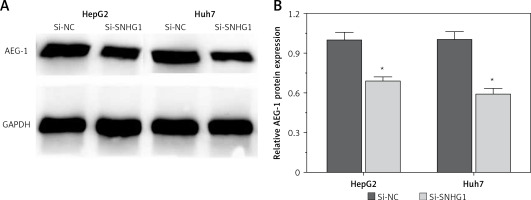

Silencing SNHG1 could significantly inhibit expression of AEG-1 protein in HCC cells

To further investigate the influence of SNHG1 on hepatocellular carcinoma cells, expression of AEG-1 protein was quantified using modern molecular techniques of qRT-PCR and Western blotting assay. The results showed that after silencing SNHG1 in both Huh7 and HepG2 cells, expression of AEG-1 significantly decreased at both mRNA and protein levels compared with the control (p < 0.05, Figure 3).

SNHG1 and miR-195 interact with and repress each other

LncRNA acts as a miRNA sponge, and mRNA has been reported to reduce regulatory effects. This function introduces an additional layer of the composite layer in the miRNA target interaction network. Major mRNA and non-coding RNA are miRNAs that may be affected by methods, including cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion of cancer. In addition, miR-195 was confirmed by luciferase assay to regulate SNHG1. A luciferase reporter vector (MUT-SNHG1 includes a predicted binding site mutation of 8BP in WT-SNHG1 and miR-195) with wild-type and mutant SNHG1 was constructed (Figure 4 A). These indicated vectors were co-transfected into HEK293 cells with miR-195 mimics or miR-195 NC; the luciferase activity was then monitored. The results showed that the luciferase activity of wt- SNHG1 vector could be significantly suppressed by miR-195 mimics; after mutation in the predicted binding sites of miR-195 in SNHG1, the effect of miR-195 mimics or miR-195 NC on luciferase activity was abolished (Figure 4 B), indicating that SNHG1 could directly bind to miR-195.

Figure 4

LncRNA SNHG1 as an endogenous sponge of miR-195. A – The lncRNA SNHG1-binding sequence in the 5′ region of miR-195; B – the relative luciferase activity of SNHG1 wild-type or mutant 3’-UTR in HEK293 cells following transfection with the miR-195 mimic or corresponding mimic NC; C – the relative expression levels of miR-195 were quantified using qRT-PCR in the Huh7 and HepG2 cells; D – the relative expression of miR-195 in tumor tissues and normal tissues; E – the negative correlation between SNHG1 and miR-195 levels in the HCC patients (R2 = –0.6625, p < 0.001)

*P < 0.05; **p < 0.01 vs. control.

In addition, the level of miR-195 was significantly down-regulated compared to the normal human liver cell line L02, indicating that there is SNHG1 expression in the HCC cell line (p < 0.01; Figure 4 C). Subsequently, qRT-PCR was performed to determine the level of miR-195 in tumor tissues. The results indicate that miR-195 is shown to be much lower in tumor tissues than in corresponding normal tissues (p < 0.01; Figure 4 D). Furthermore, correlation analysis indicated that there was a strong negative correlation between SHHG1 expression and miR-195 expression in HCC tissues (Figure 4 E). These data indicate that interaction inhibition occurs between SNHG1 and miR-195.

Discussion

Due to cancer invasion and migration and a high rate of recurrence, HCC has become one of the biggest threats to human health, with a poor prognosis and low 5-year survival rate [23]. Studies of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in various cancers have demonstrated that many lncRNAs are involved in HCC [15–17, 24–32]. However, the role of SNHG1 in cell migration and invasion in HCC still needs to be illuminated. In the present study, we demonstrated effects of inhibiting SNHG1 on cell migration and invasion in HCC, and for the first time we showed that the effect of SNHG1 on HCC cells might be through regulation of miR-195, and also AEG-1 was involved in the process.

Many studies have confirmed that the expression of lncSNHG1 was deregulated in different types of cancers such as colorectal cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and prostate cancer etc. [21, 33, 34]. However, the potential role of SNHG1 in HCC remains unknown. Consistent with previous work, our results also showed that SNHG1 was up-regulated in HCC tissues and cell lines. SNHG1 was up-regulated in non-small cell lung cancer and can promote cancer development by inhibiting miR-101-3p [35]. The results from Yan et al. found that SNHG1 was significantly up-regulated in esophageal carcinoma tissues [36]. Zhang et al. obtained similar results for SNHG1 in esophageal squamous cell cancer [37]. miR-195 was also proven to be a tumor suppressor in several cancers. Wang et al. found that miR-195 was down-regulated in colorectal cancer and was correlated with lymph node migration and poor prognosis [38]. All these results are consistent with our findings. These data indicate that SNHG1 is dysregulated in HCC and may function as an oncogene in HCC tumorigenesis.

To further investigate this mechanism, siRNA-mediated knockdown assays were used to examine SNHG1 function. We observed that knockdown of SNHG1 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion. Other results showed that down-regulation of SNHG1 could suppress cell proliferation and invasion by regulating the Notch signaling pathway in esophageal squamous cell cancer [37], but the effect of SNHG1 on cell migration in HCC was not discussed. By conducting migration and invasion assays, we for the first time demonstrated that inhibiting SNHG1 could significantly suppress both migration and invasion of HCC cells. Meanwhile expression of AEG-1 protein, which is a key protein that has been proven to promote migration and invasion of tumor cells [39, 40], was also inhibited through silencing SNHG1. Some related studies on SNHG1 in other cancers have been reported. Liu et al. demonstrated that SNHG1 could promote cell growth, migration and invasion in cervical cancer [41]. These results indicate that SNHG1 may mainly act as a stimulator of invasion and migration for tumor cells, which needs more studies for further confirmation.

Finally, we tested miR-195 as a direct target of SNHG1 and showed that SNHG1 acts as an endogenous sponge of miR-195 in HCC cells. By using the dual luciferase reporter assay, we confirmed that miR-195 is a direct target of SNHG1. The mechanism by which miR-195 is dysregulated in HCC remains unknown. In previous studies, preliminary data and bioinformatics analysis indicated that DNA methylamine plays an important and complex role in regulating miR-195 expression in HCC, indicating that miR-195 is deregulated in HCC [22]. Maintaining proliferation and avoiding apoptosis was a feature of malignant tumors. Abnormal expression of miRNAs was involved in the regulation of various cellular processes that often become dysregulated during the onset and duration of HCC [7, 42, 43]. For example, up-regulation of miR-221 in HCC increases cell proliferation, colonization and invasion, increases S-phase cell number and inhibits apoptosis [44]. miR-199a/b-3p is down-regulated in HCC, and its expression is restored by inhibiting the mTOR pathway by inhibiting HCC proliferation in tumor-promoting P21 (RAC1)-activated kinase 4 (PAK4), in vitro and in vivo [45].

The AEG-1 gene is always amplified in patients with HCC and serves a key role in regulating the hepatocarcinogenesis gene of the oncogenic Ha-Ras pathway, being transcriptionally regulated by c-Myc upon Ha-Ras and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activation [46]. Overexpression of AEG-1 activates the PI3K/Akt, nuclear factor-κB, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. Our data also documented that AEG-1 was overexpressed in HCC tissues compared with the corresponding normal liver tissues. Furthermore, an inverse correlation was observed between miR-195 and AEG-1 expression in HCC tissues. miR-195 was shown to suppress AEG-1 expression by directly binding to the 3′-UTR of AEG-1. The function of miR-195 has already been investigated in several distinct cancer types, such as non-small cell lung cancer [47], bladder cancer [48], breast cancer [49] and HCC [50]. To date, 17 genes, including PCMT1, SRC-3, CCND1, CCNE1, CDC25A, CCND3, CDK4, CDK6, E2F3, BTRC, IKKα, TAB3, VEGF, VAV2, CDC42, LATS2 and BCL-w, have been identified as targets of miR-195 in HCC [51–54]. miR-195 has also been implicated in various biological processes of HCC, including cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis, drug resistance angiogenesis and metastasis [50]. The reported targets of miR-195 and our observations suggest that miR-195 may regulate multiple signaling pathways, and that loss of miR-195 could lead to tumor progression in HCC [55].

In conclusion, we conducted an in vitro study to investigate effects of long non-coding RNA SNHG1 on cell migration and invasion in HCC. The results showed that SNHG1 could promote cell migration and invasion of HCC cells by sponging miR-195, and AEG-1 was also involved in the process. These results can provide deeper understanding of SNHG1-miR-195 in HCC and give new potential targets for treatment of HCC.