Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a common clinical, social and economic health problem. HF is a problem of over 26 million patients in the world [1], being one of the leading causes of death (the risk of death is similar to advanced cancer) and disability in the world; it is also characterized by a constantly increasing incidence [1]. Annual morbidity of HF in developed countries is 5–10 people per 1000 inhabitants [2]. Altogether, one in five adult individuals will develop HF at some point [3]. HF is associated with a large consumption of healthcare resources [4, 5]. It is an important and growing health and economic problem also in Poland, affecting as many as 800,000-1,000,000 people [6–8]. Every 9 min 1 patient with HF dies. Around 5,000 Poles die every month, and almost 60,000 die every year. This is associated with high mortality rates, which is about 12–15% per year among patients with moderate, stable HF. Nearly half of them die 4 years after receiving the diagnosis [9]. The number of hospitalizations for heart failure in Poland is estimated at 100,000 annually, and in the next 20 years it is predicted that even 250,000 patients might be hospitalized due to HF annually [10]. This is associated with very high costs of care, which mostly results from repeated hospitalizations. HF not only leads to a premature death, but it also results, through diminished functional capacity, in frequent disease exacerbations, and repeated hospitalizations, in worse quality of life, loss of work productivity, and substantial direct and indirect costs for the public healthcare system [11].

HF may also affect life expectancy, with large regional and national differences. The average life expectancy of women in the Lodz voivodeship (Poland) is 79.03 years and is half a year lower than the national average, and for men the difference is even higher (70.6 in Lodz to 71.75 years for the country) [12]. The main challenge in the treatment of HF is the availability of reliable and effective care that would allow patients and physicians to develop realistic expectations about the prognosis and to choose the appropriate therapy and monitoring method [13]. This might be ensured by innovative digital and telemonitoring solutions that might be offered to HF patients. Key areas of digitization are healthcare delivery, patient-healthcare professional interaction and proactive care and preventive interventions using new technologies. The perceived benefits (e.g., satisfaction, impact on patient quality of life and physicians’ working conditions) of the innovation define the adoption rate of the innovation by decision-makers [14–16]. However the process of implementation might not be easy; one of the biggest barriers to digitization is the reluctance of both physicians and patients to change [17]. Resistance or willingness to accept a different way of practicing medicine has had a major impact on the development process of medical technologies and products in many countries for last three decades. Moreover, it is commonly raised that online services can depersonalize the patient-physician relationship and, as the primary purpose of medical services is to protect the health or life of patients, this diminishes the benefits of digitization. This, combined with the lack of information normally obtained during a face-to-face clinical assessment, can deprive physicians of some important decision-making factors in the diagnostic process [17, 18].

The collection, exchange and production of health information is intended to complement and ensure appropriate, necessary and effective patient care. Digital medicine, through high-quality digital devices and their software, supports health and quality of life research, the broader practice of medicine, including treatment and recovery of patients, prevention, and health promotion in the community [18]. However, the effective implementation of telemedicine in cardiology (and other specialties) requires a change in both the organization (as well as the whole healthcare system) and the approach to the patient. The organizational change is supported by new technologies, management and administrative processes, the distribution of medical services and patient relations. Relationships with patients are key to improving the organization and increasing its effectiveness [19–21].

Digitization brings specialized medical services into primary care, where patients with acute cardiovascular disease (CVD) can be treated in an outpatient setting [22, 23]. In addition, the integration of digital systems in primary and specialized care, the use of common platforms with patient data, leads to essential improvement in cardiac care. A patient can be treated for chronic heart disease in a primary care setting close to home, with simultaneous specialist follow-up through a platform that monitors the patient’s condition. In primary care, teleconsultation (e-consultation), telediagnosis (e-diagnosis) and tele-education used in an integrated manner, possibly linked to tools such as decision support systems, can improve the quality of care for cardiovascular diseases, especially hypertension, atrial fibrillation, heart failure and acute myocarditis [22–25]. The most common causes of heart injury are ischemic heart disease (IHD) and hypertension. In most cases, these lead to structural changes in the heart that manifest themselves as cardiac arrhythmias [26]. Data collected via telemedicine solutions, such as ECG recordings, blood pressure values entered by the patient, body weight, biochemical test results, allow the physician to monitor the correctness of the medication taken and its effects [27]. This allows the appropriate timing of medical appointments. Digitization has also a major impact on the personalization of cardiology services [27].

The aim of the study was to implement a telemedicine model of care for patients with heart failure and, as a result, prevent heart failure exacerbations and cardiovascular deaths. Through well-designed care and an educational panel, emphasis was placed on prevention. In this pilot program we used a dedicated online platform that was used to coordinate activities around the patient with an emphasis on patient’s education. The platform was intended to enable the acquisition and management of medical data by physicians and nurses, as well as to be a tool for providing services, such as teleconsultation and remote monitoring.

Material and methods

General information

The project on the implementation of the telemedicine model in the field of cardiology by the Institute of the Polish Mother’s Health was a prospective, multicenter, interventional study conducted among consecutive heart failure patients in Poland.

There were the following inclusion criteria in this study: (1) age ≥ 18 years; (2) informed consent to participate expressed in writing or electronically (in accordance with applicable law); (3) confirmed diagnosis of heart failure, in accordance with the current guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [13], (4) having a smartphone with the Android system or a computer to install a telemonitoring application.

Patient recruitment took place as follows:

During hospitalization: during a hospital stay due to HF exacerbation or HF diagnosis de novo, the attending physician proposed the patient’s participation in the project and took appropriate consent;

During an outpatient visit to a cardiologist: some (although a minority) HF diagnoses were made in an outpatient setting – then the cardiologist had also the opportunity to invite the patient to participate in the study;

Telephone contact: this form of contact was dedicated to patients registered in a given primary health care facility who had already been diagnosed with HF. The conversation consisted of proposing participation and presenting the potential benefits of participation. During an outpatient visit at a primary care physician, similarly to the scenarios presented above, the primary care physician also had the opportunity to invite the patient to participate in the project.

Quality of life was assessed with EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire, a self-assessed, health related, quality of life questionnaire. The EQ-5D-5L is a brief, multiattribute, generic, health status measure composed of 5 questions with Likert response options (descriptive system) and a visual analog scale (EQ-VAS). The latter asks patients to rate their own health from 0 to 100 (the worst and best imaginable health, respectively). The descriptive system covers 5 dimensions of health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression) with 5 levels of severity in each dimension (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and unable to perform or extreme problems).

The whole study was led by the team of the Department of Cardiology and Congenital Heart Diseases from the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital Research Institute (PMMHRI) of 10 cardiologists with 7 external primary care centers that participated in the study.

Type of intervention

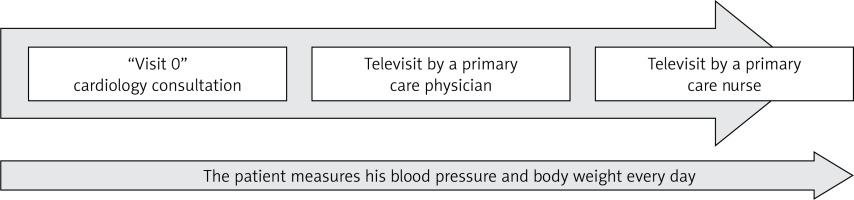

After obtaining formal consent, the patient attended “Visit 0” at the PMMHRI. Alternatively, based on promotional materials, the patient could choose one of the primary care physicians’ centers taking part in the program to participate in the pilot program. Then the role of the primary care physician was to carefully check the inclusion and exclusion criteria and collect relevant documents from the patient (Figure 1).

The recruitment visit (referred as “Visit 0” took place within the framework of the scenarios proposed above at a cardiologist’s office in order to develop a patient’s treatment plan by a specialist) consisted of accurate provision of information regarding the pilot project, potential benefits and possible threats, collecting appropriate consent and short training on how to use the platform and instructions on how to use the dedicated tutorial, or who to seek help in case of technical problems. This visit involved supervision of the patient during the first, sample measurements of body weight, blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR), informing the patient about his/her current health condition, threats, prospects and plans for further treatment and conducting a survey and preliminary questionnaires. The patients received medical equipment in the form of an electronic scale measuring body weight (kg), an electronic BP monitor measuring systolic blood pressure (SBP, mm Hg) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP, mm Hg). The patients were asked to take their BP measurements twice daily (at 9 a.m. and 7 p.m.) and weigh once daily (in the morning on an empty stomach), communicating the results using an online platform. During Visit 0 a cardiology consultation was also performed when the patient was included at the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital Research Institute or it was performed during 2 weeks if the patient was enrolled in one of the primary care centers. During this consultation, patients were interviewed and examined, received information about pharmacological treatment with simultaneous modification when needed, assessment regarding the necessity of implantable resynchronization therapy and/or implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), and received educational material about HF diet, exercise training, optimal lifestyle changes and self-monitoring.

After a month ± 5 days, Visit 1 in the primary care setting took place. This visit was a typical medical teleconsultation, during which the patient reported vital signs and assessed symptoms. At its conclusion, a note from the visit and information with further recommendations for the patient was posted on the platform. If disturbing symptoms occur, the patient was referred for an urgent cardiology consultation or directly to the hospital emergency room, depending on the patient’s condition. The primary care physician’s task was to take care of the patient’s health and perform regular examinations and televisits, which complemented specialist care. As part of his/her activity, the primary care physician was able to change the dosage of drugs or add or discontinue single drugs; however, the cardiologist was the attending physician. The primary care physician also provided the patient with prescriptions. In the event of a gradual, constant deterioration of the patient’s health, the primary care physician was able to ask the cardiologist for an urgent visit or, depending on the need, hospitalization. The role of a primary care physician was not limited to treating only cardiovascular diseases. A primary care physician generally took comprehensive care of the patient’s health and looked at it from a broader perspective. For this reason, the primary care physician coordinated treatment with other specialists (e.g., pulmonologists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, etc.), if necessary. HF patients usually had numerous burdens, and patient care should not be limited to only one disease entity. The platform also included information about other, parallel/simultaneous treatment processes, so that the cardiologist took into account, for example, oncological treatment and related planned hospitalizations. The primary care physician had also the opportunity to access the platform with reports prepared by the patient regarding his/her BP and body weight control, which was intended to facilitate patient care.

The nursing consultation took place 2 months after inclusion. In Poland, the role of nurses in coordinated care programs is overlooked, despite the fact that such support has proven its effectiveness in clinical trials conducted in our country and around the world [14]. Nurses contacted the patient mainly by telephone, interviewed the patient according to a previously prepared form. Simple algorithms allowed them to assess whether a patient required urgent consultation with a physician as part of outpatient or hospital care. In addition, a very important role of nurses in the study was patients’ health education. Thus, after completing the form, the second part of the nursing televisit was patient education, which was individually tailored based on the burden and comorbidities. After each teleconsultation, the nurse posted an entry on the platform with information what the conversation was about, what the patient was educated about and the result of the prepared form along with the application (e.g. the patient was referred to a cardiologist on a scheduled basis/the patient does not require an urgent visit/the patient was sent to the emergency room).

Finally, there was a final visit with the physician (Visit 3; Figure 1), which was planned 3 months after the inclusion to the study. It was a typical consultation or teleconsultation including an assessment of the reported parameters and the patient’s condition. The patient received detailed recommendations regarding further treatment. During the consultation, the endpoints of the project were assessed, including quality of life, prognosis, and frequency of unplanned hospitalizations, and a final follow-up questionnaire was conducted. A questionnaire was conducted in all patients after enrollment in the study and after 3 months of telemonitoring and educational process. The questionnaire included the original survey regarding HF state, signs and symptoms, comorbidities, number of hospitalizations in the last year, pharmacotherapy as well as Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, strength, assistance with walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls (SARC-F) questionnaire, the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), Beck Depression Inventory, heart failure knowledge questionnaire and European Heart Failure Self-care Behavior Scale (9-EHFScBS).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted using the following tools: Statistica 13.1 (StatSoft, Poland) and PQStat (PQStat Software, Poland). The distribution of continuous data was determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. As all continuous data presented the non-normal distribution, therefore they were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test. The categorical data were examined using χ2 or χ2 with Yates correction or Fisher test. The logistic regression model was used to calculate the propensity score for each subject in the database. The propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted by the neighbour method with the 1 : 1 ratio. A p-value below 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

General characteristics

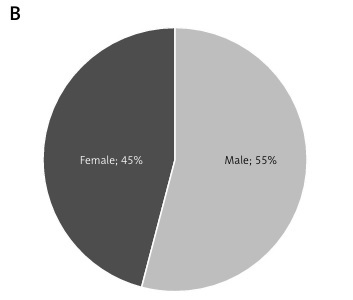

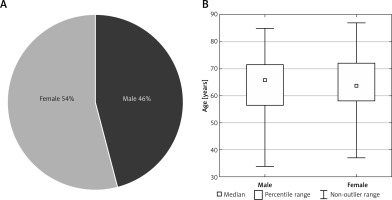

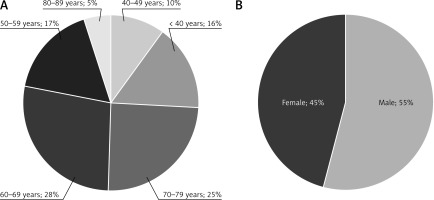

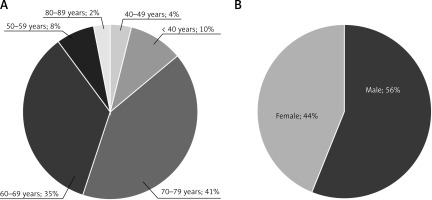

The study finally included 140 men with an average age of 66 years (standard deviation [SD] 56–71) and 163 women with an average age of 64 years (58–72) (Figure 2). 39% of men and 53% of women had no knowledge regarding the type of their HF. There were no differences in mean SBP and DBP (mm Hg) between men and women at the inclusion (133 [120–149] vs. 124 mm Hg [106–146]; p = 0.10) and (81 [74–93] and 77 mm Hg [67–88; p = 0.10] as well as in heart rate (70 [62–75] vs. 67 beats/min [61–79]; p = 0.70]. Men had higher body mass index (BMI) than women (kg/m2) (30 [26–32] vs. 28 [25–31]), and most of the included patients were overweight and obese. The average time from diagnosis of HF was 7 (3–15) years for men and 10 (4–16) for women (p = 0.70).

The ischemic etiology of HF was present in 78% of men and 73% of women (p = 0.40). 31% of men and 16% of women declared myocardial infarction (MI) in the past (p = 0.002), and 53% of men and 51% of women had coronary heart disease (CHD (p = 0.64). 63% of men and 33% of women had coronary angiography in the history (p = 0.0001), and 34% of men and 14% of women had stents implanted in coronary vessels (p = 0.0001). 26% of men and 34% of women reported a history of surgery because of cardiological reasons (p = 0.013). Men more often suffered from myocarditis than women (18% vs. 9%; p = 0.01) and survived sudden cardiac arrest (7.86% vs. 1.23%; p = 0.004). Finally, more men had implantable cardiac devices compared to women (16% vs. 3%) (p = 0.001).

Women more often than men suffered from cancer, depression and thromboembolic events and less frequently from obstructive sleep apnea – distribution of all comorbidities is presented in Table I.

Table I

Comorbidities in the study group separately for men and women.

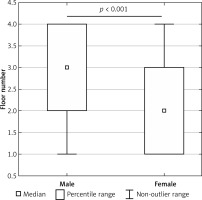

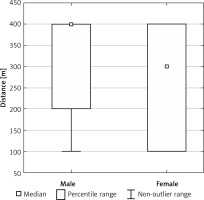

The type of HF and distribution of symptoms in men and women

The mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 43% (30–58) for men and 57% (45–63) for women (p = 0.0001), and women in the study suffered mainly from heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). 35% of men and 18% of women were hospitalized in the last year because of HF aggravation (p = 0.0001) and 16% of men and 13% of women because of other causes (p = 0.47); however there were no differences between genders regarding the number of hospitalizations in last 12 months (p = 0.80). The men, despite lower LVEF, felt short of breath/tired when climbing the stairs up than women (3 [2–4] vs. 2 floors [1–3]; p = 0.001]), had higher distance in meters when walking on flat ground (400 [200–400] vs. 300 m [100–400]; p = 0.0001) and less frequently had to get up to go to the toilet at night (p = 0.03) (Figures 3, 4). Analysis of the rest of heart failure symptoms is presented in Table II.

Table II

Analysis of heart failure symptoms in men and women

Men also suffered significantly less often from shortness of breath at rest, swelling of the lower limbs and shortness of breath that wakes them up at night (p < 0.05). On the other hand, women were more likely to report shortness of breath that woke them up at night. There were no statistically significant differences between both genders when asked about the need to sleep on more pillows or the need to urinate at night.

Lifestyle, education and self-assessment in the population of heart failure patients and differences between men and women

Men reported more often alcohol consumption, smoking, and less frequently any physical activity. 47% of men reported erectile dysfunction. More than 90% of patients took medications regularly, but only 35% of men and 19% of women had HF self-care training as well as only 35% of men and 46% of women knew how to increase the dose of diuretic on their own if shortness of breath or swelling increases (Table III).

Table III

Lifestyle, education and self-assessment in the population of heart failure patients

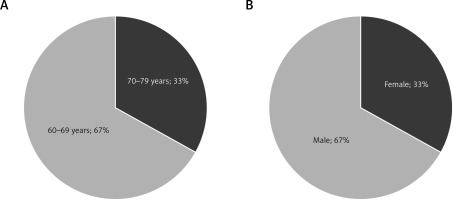

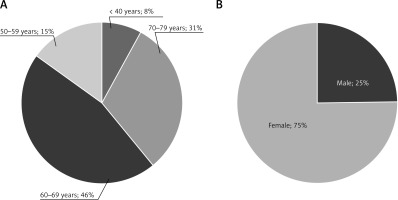

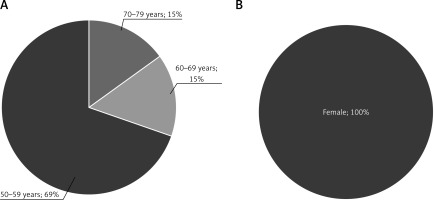

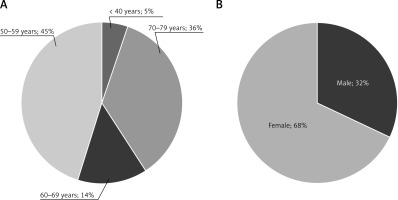

Quality of life in men and women and according to age groups

Based on the results from the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire significantly more women than men reported moderate (60% vs. 40%) and serious (71% vs. 29%) problems with moving around, and 67% of men and 33% of women reported serious problems with self-care. 68% of women and 32% of men observed serious problems with performing ordinary activities independently. 62% of women and 38% of men had a moderate pain problem, and 75% of women and 25% of men had a serious pain problem. These problems were significantly more frequently noticed after 50 years old (Figures 5–8). A significant level of anxiety or depression as an important problem of everyday life mainly concerned patients aged 50–59 (69%). 56% of women and 44% of men showed a moderate level of anxiety or depression, and only women showed a significant level of anxiety (Figures 9, 10).

Figure 7

Significant problems with performing everyday activities according to age (A) and gender (B)

Discussion

The effectiveness of telemonitoring in HF patients has been a topic of debate for several years with conflicting opinions arising from various studies [28, 29]. While some studies have shown positive outcomes associated with telemonitoring/telehealth interventions, others have reported contradictory results, leading to a lack of consensus on its overall impact and in the body of current heart failure guidelines [4]. A study by Frederix et al. showed that noninvasive telemonitoring reduced all-cause mortality and HF-related hospitalizations, providing strong evidence for the benefits of telemonitoring in HF management [30]. On the other hand, other studies showed that home telemonitoring in HF patients was non-inferior when compared to the traditional approach to treatment [31]. When one study, such as Brons et al. [32] highlighted conflicting results regarding the algorithms used in telemonitoring programs for HF patients, other authors like Zavertnik et al. emphasized the importance of interventions promoting self-care through patient education and telemonitoring. These differing perspectives underscore the complexity of evaluating the impact of telemonitoring in HF patients [33].

It is known that the pathophysiological underpinnings of HF in women often differ from those in men. Women are more frequently diagnosed with HFpEF, a condition that is associated with a higher prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction [34, 35]. Our study also confirmed this interesting fact. HFpEF is exacerbated by factors such as fluid redistribution and age-related changes in cardiac structure, which contribute to the higher symptomatic burden observed in women [36, 37]. Our findings also support this thesis; we showed that the three main symptoms of HF appeared significantly more often in women than in men. The symptom burden has been linked to increased morbidity and mortality rates. Women tend to report a higher frequency and severity of symptoms, which can adversely affect their quality of life [38, 39]. In our study, the patients were asked about several symptoms related to quality of life, both physical and mental. We showed that women significantly more often suffered from symptoms mentioned. The interplay of these symptoms highlights the need for gender-specific approaches in the management of HF, as women may respond differently to treatments and exhibit varying outcomes compared to men [40]. Another conclusion from our analysis is that women smoke cigarettes and drink alcohol significantly less, but they are more likely to be physically active than man. Researchers indicate that women with chronic HF exhibit better self-care maintenance compared to men, largely due to their greater knowledge of heart failure and its management [41]. This knowledge translates into more proactive health behaviors, such as adhering to medication regimens and monitoring symptoms. Furthermore, studies have shown that female caregivers significantly influence the self-care maintenance of heart failure patients, suggesting that the social support provided by women enhances self-care practices [42].

In the current analysis, women were twice as likely to develop cancer than men [43]. Among many factors, experts believe there are several main reasons for the increased incidence of cancer in the group of patients struggling with HF daily. Evidence suggests that women with heart failure may experience a higher incidence of cancer compared to their male counterparts [44]. This phenomenon can be attributed to various factors, including biological differences [45], the impact of comorbidities, and the effects of cancer treatments on cardiovascular health [46]. The relationship between HF and cancer, particularly in women, is a complex and multifaceted issue. Research indicates that women diagnosed with certain types of cancer, such as breast cancer, are at an increased risk of developing heart failure. Abdel-Qadir et al. found that women with early-stage breast cancer had a higher incidence of HF compared to cancer-free controls, which underscores the interplay between these two serious health conditions [47]. This association may be due to the cardiotoxic effects of some cancer treatments, such as anthracyclines and trastuzumab, which are known to adversely affect cardiac function [48]. Additionally, postmenopausal women with breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers have been shown to have an increased risk of cardiovascular conditions, including HF, prior to receiving endocrine therapy [49]. Therefore, based on our results and evidence from the literature, women suffering from heart failure, especially those after oncological treatment in the past, should be under close medical supervision throughout their lives not only in the context of modern cardiological treatment, but also from the point of view of broadly understood disease prevention.

Limitations of the study. The limitation of the study is a relatively small number of study participants, among whom the proportions between both genders are not equal. Another limitation is associated with a relatively short follow-up. Older patients quite often reported problems with using both the equipment and the mobile phone application, which was related to the lack of measurements during observation.

In conclusion, we observed that women suffer more from HF symptoms and have worse quality of life assessed in EQ-5D-5L than men despite their higher left ventricular ejection fraction. Using the online platform with the continuous monitoring of HF patients might essentially reduce the number of cardiological consultations and the risk of HF-related hospitalizations; it might also improve quality of life of these patients. These results need to be confirmed in longer follow-up and further studies with a larger group of patients with HF.