Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common chronic degenerative disease [1] and its prevalence increases with the aging of the population [2–4]. It is one of the major causes of joint pain, disability and decreased quality of life [1, 5]. This condition affects mainly the weight-bearing joints (knees and hips) in middle-aged and elderly people [1, 2]. Management mostly includes both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. However, in cases of end-stage OA when the symptoms become more severe and non-surgical treatment options do not give an adequate response, patients are treated by total joint arthroplasty [2], leading to a clear improvement in quality of life [6].

Over the last decades in the assessments of functional ability of patients with knee and hip OA in clinical studies, the individual’s perception of physical function has been given the value of an endpoint. Consequently, a number of self-reported disease-specific questionnaires have been developed and validated [3, 7], including the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) and the Oxford Hip Score (OHS), for the quantification of knee and hip functional status [8–10]. Over time, it has become obvious that the problems associated with OA have a significant impact on an individual’s overall health status, including multiple dimensions of health-related quality of life (HRQoL). As a result, numerous generic self-reported questionnaires have been developed for evaluation of the patients’ perception of general health, including the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) [11]. Thus, in clinical studies, both disease-specific and generic self-reported questionnaires became important outcome measures.

The function and HRQoL appear to rest upon a complex interaction of different factors, not only on the structural damage of affected joints. Numerous studies have referred to factors related to poor function and HRQoL, where knee OA was more frequently evaluated than hip OA [1, 3, 5, 7, 12–28], suggesting that contributions of these factors to disability remain controversial. However, there is limited research referring to the association of different factors with function and HRQoL in end-stage knee or hip OA [29–35].

Currently in Serbia, patients with end-stage knee or hip OA prolong undergoing a total joint arthroplasty; therefore, it is expected that one has a more impaired function and HRQoL. Thus, it is important to understand the factors which contribute to poor function and HRQoL. To the best of our knowledge, the association of different factors with self-reported function and HRQoL in patients with end-stage knee or hip OA has not been studied in Serbia so far.

The purpose of the present study was twofold: first to evaluate patients’ perception of function and HRQoL in patients with end-stage knee or hip OA immediately prior to total joint arthroplasty, and second, to identify the factors (sociodemographic, clinical and psychological) associated with poor self-reported function and physical and mental dimension of HRQoL.

Material and methods

Patients

In the cross-sectional study, 245 patients admitted from January 2016 to October 2017 to the Orthopedic Clinic, Clinical Center Nis (Serbia) in order to undergo primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or total hip arthroplasty (THA) were recruited.

Only patients with end-stage knee or hip OA were included, while those with indications other than OA were excluded. Also, other exclusion criteria were: patients with severe chronic diseases limiting physical functioning, cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination score < 24) [36], and refusal to participate in the study. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 200 patients (100 with knee and 100 with hip OA) were eligible for the study and written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Nis.

Data collection

The patients were assessed 24–48 h before surgery. The socio-demographic data, duration of the disease symptoms and comorbidity were collected through face-to-face interviews and from medical records. The patients’ body height and weight measures were taken, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kg/m². Then, knee/hip flexion range of motion (ROM) and flexion contracture were measured objectively and after that the patients filled in seven self-reported questionnaires. When administration was done, one of the investigators checked whether all fields were filled in, and if they were not, the questionnaire was immediately handed back to provide the missing answers.

Comorbidity

Comorbidity was assessed by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), originally developed and validated as a predictor of mortality in hospitalized patients. It includes 19 conditions; each of them was assigned 1, 2, 3 or 6 points. CCI was expressed as the summative score in the range 0–33 [37].

Knee/hip active flexion ROM and flexion contracture

The active knee and hip flexion ROM was measured in degrees using a long-arm, full-circle handheld goniometer. The patient was placed in a supine position on an examination table with hips in the neutral position and knees extended. The goniometer was centered on the knee or hip joint. Then the patient moved the knee or hip to the maximum flexion and the degree of flexion was measured and recorded. While returning to the starting position of full extension, the limited motion was measured and expressed as flexion contracture. Hip and knee ROM was measured and recorded in degrees according to the method suggested by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons [38]. The same investigator with more than 10 years of experience measured ROM at all assessment time points with the same goniometer (made of flexible clear plastic) twice and the mean value was recorded.

Pain intensity

Pain intensity in the affected joint (knee or hip) was measured by the 11-point Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imagined). The patients were asked to mark the scale number corresponding to their average pain intensity during the last 4 weeks.

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured using the self-administered 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire. For each of the 7 statements concerning anxiety symptoms, the patients indicated how often during the last 2 weeks the symptoms had bothered them, with scoring from 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half of the days) to 3 (nearly every day) [39, 40].

Depression

Depression was assessed using the self-administered 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), validated for depression severity. For each of the 9 statements concerning depressive symptoms, the patients indicated how often during the last 2 weeks they had been bothered by any of them, where the scores ranged from 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than 7 days) to 3 (nearly every day) [41, 42].

Fear of movement

Fear of movement was assessed using the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK), which is a 17-item self-reported questionnaire. Each item is provided with a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The patients were asked to mark their personal level of agreement or disagreement with each item of this scale [15, 43].

Catastrophizing

Catastrophizing was assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (pCS), an instrument for measuring catastrophic experience and thinking related to pain. It is a self-reported questionnaire consisting of 13 items describing different thoughts and feelings when individuals are in pain. Participants are asked to rate the degree to which they experienced each thought and feeling about pain, on a five-point Likert type scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time) [14, 44].

Dependent variables

Self-reported function

The function of the knee or hip joint was estimated using the OKS translated into Serbian [45] or the OHS also translated into Serbian [46], which are designed and validated as self-reported joint-specific questionnaires for evaluating outcomes of TKA or THA [8, 9]. Both OKS and OHS consist of 12 questions, five of which refer to pain and seven to function during the last 4 weeks. The updated version 0–48 was used [47]. There is growing interest to use these questionnaires in the assessment of function in patients with knee and hip OA [10].

Self-reported HRQoL

HRQoL was estimated using 36-Item Short Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2) translated into the Serbian language [48]. It is a generic self-reported questionnaire designed and validated for the assessment of HRQoL in general and populations with specific conditions, and includes one scale for each of the eight measured health domains: physical functioning (PF), role limitation due to physical health – role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality, social functioning (SF), role limitation due to emotional health – role emotional (RE) and mental health (MH). Two standardized summary scores can be calculated from the SF-36: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS), which are related to the physical and mental dimensions of HRQoL. The PCS score correlates most highly with the three subscales PF, RP and BP, whereas the MCS score correlates most highly with the MH, SF, and RE. The GH and vitality subscales correlate moderately with both physical and mental health [11].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 15.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Separate analyses were done for patients with knee and hip OA. Continuous variables (age, BMI, duration of symptoms, CCI, NRS, OKS/OHS, flexion ROM, flexion contracture, pCS, TSK, GAD7, PHQ9) are given as means ± SD (medians). Categorical variables (gender, marital status, employment status) are given as absolute numbers, and in percentages (%). Dependent variables were: OKS/OHS and the two SF-36 component summary scores (SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS). Univariate linear regression analyses were used to identify the factors significantly associated with dependent variables. Only independent variables significantly associated with the aforementioned dependent variables (OKS/OHS, SF-36 PCS, SF-36 MCS) at the univariate level of analysis were included in the subsequent multivariate linear regression analysis. Statistical power (1-β) to detect significant correlations between examined variables in the study were calculated and expressed as percentages (%). Significant variables from the resulting model, together with the age and gender, were unconditionally included in the final model. Statistical significance was defined as a p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study included 200 patients, 100 with knee and 100 with hip OA, aged 40–90. Baseline socio-demographic, clinical and psychological characteristics of the patients are shown in Table I. The self-reported function was poor (mean: OKS 10.7 points and OHS 13.9 points), as was the physical dimension of HRQoL (SF-36 PCS 26 for knee OA and 28.3 for hip OA), while mental dimension was not impaired (SF-36 MCS 52.1 for knee OA and 53.8 for hip OA).

Table I

Characteristics of study patients

[i] OA – osteoarthritis, BMI – body mass index, CCI – Charlson Comorbidity Index (higher score indicating higher comorbidity burden), NRS – Numerical Rating Scale (higher number of points indicating a higher intensity of pain), ROM – range of motion, OKS – Oxford Knee Score (higher score representing better function), OHS – Oxford Hip Score (higher score representing better function), SF–36 PCS – 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Physical Component Summary (higher score indicating better physical health), SF–36 MCS – 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Mental Component Summary (higher score indicating better mental health), pCS – Pain Catastrophizing Scale (higher score indicating higher degree of pain catastrophizing), TSK – Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (higher score indicating higher degree of fear of movement), GAD7 – 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (higher score indicating higher degree of anxiety), PHQ9 – 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (higher score indicating higher degree of depression).

Self-reported knee/hip function (OKS/OHS)

The association of OKS/OHS score and significant factors, according to univariate regression analysis, is shown in Table II. In knee OA, poor self-reported function was associated with female gender (p < 0.001), higher BMI (p = 0.019), higher pain intensity (p < 0.001), reduced flexion ROM (p = 0.005) and higher scores of all psychological variables: pCS, TSK, GAD7, and PHQ9 (p < 0.001, p = 0.018, p < 0.001, p = 0.011).

Table II

Factors significantly associated with self-reported knee or hip function (OKS/OHS): results from univariate regression analyses

[i] r2 – coefficient of determination, B – univariate unstandardized linear regression coefficients, OA – osteoarthritis, OKS – Oxford Knee Score, OHS – Oxford Hip Score, BMI – body mass index, NRS – Numerical Rating Scale, ROM – range of motion, pCS – Pain Catastrophizing Scale, TSK – Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia, GAD7 – 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PHQ9 – 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, – empty spaces, factors not significantly associated with self-reported knee or hip function (OKS/OHS).

In hip OA, poor self-reported function was associated with being unemployed (p = 0.031), higher BMI (p = 0.037), higher pain intensity (p < 0.001), reduced flexion ROM (p < 0.001), higher degree of flexion contracture (p = 0.003) and higher scores of all psychological variables: pCS, TSK, GAD7, and PHQ9 (p < 0.001, p = 0.002, p = 0.016, p = 0.015).

There is high statistical power of the study for the tested parameters (pCS, TSK, GAD7 and PHQ9) both for knee and hip (Table II).

HRQoL (SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS)

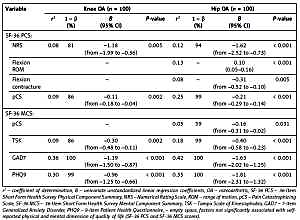

The association of SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS scores and significant factors is shown in Table III. In knee OA, the poor physical dimension of HRQoL was associated with higher pain intensity (p = 0.005) and higher pCS score (p = 0.002), while the mental dimension of HRQoL was associated with higher scores of TSK (p = 0.002), GAD7 and PHQ9 (p < 0.001) scores.

Table III

Factors significantly associated with self–reported physical and mental dimension of quality of life (SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS scores): results from univariate regression analyses

[i] r2 – coefficient of determination, B – univariate unstandardized linear regression coefficients, OA – osteoarthritis, SF-36 PCS – 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Physical Component Summary, NRS – Numerical Rating Scale, ROM – range of motion, pCS – Pain Catastrophizing Scale, SF-36 MCS – 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Mental Component Summary, TSK – Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia, GAD7 – 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PHQ9 – 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, – empty space, factors not significantly associated with self-reported physical and mental dimension of quality of life (SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS scores).

In hip OA, the poor self-reported physical dimension of HRQoL was associated with higher pain intensity (p < 0.001), reduced flexion ROM (p < 0.001), a higher degree of flexion contracture (p = 0.005) and a higher pCS score (p < 0.001). The mental dimension of HRQoL was associated with higher scores of all examined psychological variables: pCS (p = 0.031), TSK, GAD7, and PHQ9 (p < 0.001).

There is high statistical power of the study for the tested parameters of SF-36 PCS (NRS and pCS) and SF-36 MCS (TSK, GAD7 and PHQ9) both for knee and hip (Table III).

Results of multivariate regression analysis

Multivariate linear regression analysis results are shown in Table IV. Based on the value of r2 , it was noted that in knee OA, 56% of the variance of the OKS was determined by a set of four variables (pCS, Flexion ROM, NRS and GAD7), while in hip OA, 44% of the variance of the OHS was determined by a set of three variables (pCS, Flexion ROM and being employed) that are included in the final regression model (Table IV). Considering the physical dimension of HRQoL, in knee OA 10% of the variance of SF-36 PCS was determined by the pCS score, while in hip OA, 34% of the variance of the SF-36 PCS score was determined by a set of two variables that are included in the final regression model (pCS and Flexion ROM). Further, for the mental dimension of HRQoL, in knee OA, 38% of the variance of the SF-36 MCS was determined only by the GAD7 score, while in hip OA, 48% of the variance of the SF-36 MCS score was determined by a set of two variables (GAD7 and PHQ9).

Table IV

Factors significantly associated with self-reported hip or knee function (OKS/OHS) and physical and mental dimension of quality of life (SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS scores): results from multivariate regression analyses

| Knee OA (n = 100) | Hip OA (n = 100) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r2 | B | 95% CI | p-value | r2 | B | 95% CI | p-value | |

| OKS/OHSa: | 0.56 | – | 0.44 | – | ||||

| pCS | – | –0.18 | from –0.26 to –0.11 | < 0.001 | – | –0.23 | from –0.30 to –0.16 | < 0.001 |

| Flexion ROM | – | 0.03 | 0.01–0.06 | 0.015 | – | 0.07 | 0.02–0.12 | 0.005 |

| Employed | – | 3.07 | 0.56–5.58 | 0.017 | ||||

| NRS | – | –1.84 | from –2.61 to –1.07 | < 0.001 | – | – | ||

| GAD7 | – | –0.17 | from –0.34 to –0.01 | 0.043 | – | – | ||

| SF-36 PCSa: | 0.10 | – | 0.34 | – | ||||

| pCS | – | –0.11 | from –0.19 to –0.03 | 0.008 | – | –0.20 | from –0.28 to –0.13 | < 0.001 |

| Flexion ROM | – | – | 0.07 | 0.02–0.12 | 0.009 | |||

| SF-36 MCSa: | 0.38 | – | 0.48 | – | ||||

| GAD7 | – | –1.26 | from –1.59 to –0.93 | < 0.001 | – | –1.25 | from –1.74 to –0.75 | < 0.001 |

| PHQ9 | – | – | – | –0.88 | from –1.46 to –0.29 | 0.004 | ||

Age and gender were forced into all models, r2 – coefficient of determination, B – multivariate unstandardized linear regression coefficients, OA – osteoarthritis, OKS – Oxford Knee Score, OHS – Oxford Hip Score, pCS – Pain Catastrophizing Scale, ROM – range of motion, NRS – Numerical Rating Scale, GAD7 – 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder, SF-36 PCS – 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Physical Component Summary, SF-36 MCS – 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Mental Component Summary, PHQ9 – 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; – empty space, factors not significantly associated with self-reported hip or knee function (OKS/OHS) and physical and mental dimension of quality of life (SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS scores).

Discussion

Main results and comparisons with literature

In the present study, the patients with end-stage knee or hip OA had poor self-reported function and physical dimension of HRQoL, whereas the mental dimension of HRQoL was not impaired. The better mental dimension of HRQoL was in contrast with our expectations and previous researchers dealing with OA, who reported both physical and mental dimensions of HRQoL as impaired [29]. The explanation of sustained mental dimension of HRQoL in the presence of impaired physical dimension could be assumed by effects of different cultures on HRQoL.

The study aimed to identify the factors (sociodemographic, clinical and psychological) associated with the poor self-reported disease-specific function and physical and mental dimension of HRQoL in the patients with end-stage knee or hip OA immediately prior to joint arthroplasty. Since we did not find an impaired mental dimension of HRQoL, we will further discuss an association with function and physical dimension of HRQoL.

Our study demonstrated that similar factors contribute to poor function and physical dimension of HRQoL in both knee and hip OA. In hip OA, self-reported function was determined by the pCS score, flexion ROM and being employed, while the physical dimension of HRQoL was determined by the pCS score and flexion ROM. In knee OA, knee function was determined by flexion ROM, pCS, NRS and GAD7 scores, whereas the physical dimension of HRQoL was determined by the PCS score.

Pain is the main clinical feature of knee and hip OA. We found highly significant associations between pain intensity and poor self-reported function and physical dimension of HRQoL in both knee and hip OA. The relationship of higher pain intensity with self-reported physical disability is well established in knee OA [1, 5, 12, 16, 21, 22, 24, 27, 28, 32–34] and in hip OA [1, 27, 28, 34], as well as with poor physical dimension of HRQoL (by SF-36) in knee OA [5, 7, 19]. It should be emphasized that in most studies for self-reported function assessment in knee or hip OA, the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) has been used [1, 12, 21, 28, 32–34]. However, other investigators used the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale [22, 24], Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [5], or Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure [16], whereas we decided to use the OKS/OHS. The majority of studies were of cross-sectional design, but also in a few longitudinal studies, higher pain intensity at baseline has been shown to predict worsening of self-reported function over 1-year follow-up [28] and over 5-year follow-up [1] both in knee and hip OA. From the above-mentioned studies, only a few dealt with end-stage knee or hip OA [32–34].

Reduced flexion ROM is considered to be a characteristic feature of end-stage knee and hip OA. There are conflicting results in the literature considering the contribution of reduced flexion ROM to self-reported physical disability in knee or hip OA. In line with our study, reduced flexion ROM was significantly associated with poor function in hip OA [3, 20, 27, 34] or knee OA [5, 27, 32, 34] as well as with the physical dimension of HRQoL in knee OA [5]. Steultjens et al. [25] reported that flexion ROM appears to be an important determinant of physical function in knee but not in hip OA. In contrast, some investigators found no association of flexion ROM either with self-reported function in both knee and hip OA [1, 28] or with the physical dimension of HRQoL in knee OA [7]. A possible explanation for such discrepancies might be much higher flexion ROM in their studies than in ours [1, 7, 28]. The suggested threshold of flexion ROM required for adequate function is ≥ 95º for hip flexion, and ≥ 110º for knee flexion [34]. It is also important to emphasize that in all studies flexion was measured actively, except for the study of Pua et al. [20], where flexion was measured passively. However, it is important to point out that only a few of the above-mentioned studies dealt with end-stage knee or hip OA [31, 32, 34].

A substantial body of literature suggests that psychological factors are a common byproduct of chronic musculoskeletal pain; thus they are present more often in patients with OA, including other rheumatic conditions as well, than in healthy subjects [12, 14, 15, 17, 21–24, 26, 27, 49]. Therefore, they could be risk factors for poor function and HRQoL. In our study, pain catastrophizing, anxiety, depression and fear of movement were associated with the self-reported function, whereas only pain catastrophizing was associated with the physical dimension of HRQoL in knee and hip OA. Similar results were reported by Wood et al., in patients with end-stage knee or hip OA, but they evaluated the inverse impact of function on psychological factors [35].

Over the last two decades, catastrophizing has become a significant interest in patients with chronic pain [14, 16, 17, 22–24, 33, 50]. It is characterized by the tendency to magnify the threat value of a pain stimulus along with a sense of helplessness in the presence of pain, as well as by a relative inability to inhibit pain-related thoughts in anticipation of, during, or following a painful event. To assess the extent of catastrophizing, we chose the pCS, because it estimates three domains of catastrophizing (magnification, helplessness, and rumination) [44]. In our study, the association of catastrophizing and self-reported function and physical dimension of HRQoL was highly significant in both knee and hip OA. It is important to point out that the average pCS score was much higher in our investigation than in other studies [14, 16, 17, 23, 33], for which we have no particular explanation except for the fact that the questionnaire was filled in 1 to 2 days prior to surgery. The results of the present study confirm the findings of numerous studies that have shown that higher catastrophizing contributed to greater disability in knee OA [16, 17, 22–24, 33]. Shelby et al. [22] suggest that the relationship between catastrophizing and physical disability was fully mediated by self-efficacy for physical function. Somers et al. [24] pointed out that the association of pain catastrophizing was much higher with pain and psychological disability than with physical disability in knee OA. However, Shelby et al. [22] and Somers et al. [24] evaluated catastrophizing by the Coping Strategies Questionnaire, which evaluates only the helplessness dimension. In contrast to our and the aforementioned studies [14], in patients with knee OA, no association between pCS and self-reported function was found. A possible explanation for a lack of association could be that two thirds of their participants had a mild level of OA.

Considering anxiety and depression, we found that both anxiety and depression were significantly associated with the function in both knee and hip OA. In knee OA, the role of anxiety in poor function and physical dimension of HRQoL is well established [12, 14, 21, 23, 27, 30]. Also, van Baar et al. found a significant association between anxiety and function in hip OA [27], whereas Summers et al. found a moderate correlation between anxiety and physical dimension of HRQoL in patients who had both knee and hip OA [26]. In the domain of depression, in knee OA, there is a disagreement with a few studies demonstrating an association between depression and function [26, 30, 33], while others did not find one [12, 14, 21, 23, 27]. Also, in hip OA, it was reported that depression did not contribute to poor function [3, 27].

The fear of a negative effect of movement on functioning in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, including OA, has previously been demonstrated [15]. In our study, the fear of movement level was associated with the poor function in both knee and hip OA, which is consistent with findings from several studies in patients with knee OA [14, 23, 24, 33]. In contrast to our findings, Helminen et al. found an association between fear of movement and physical dimension of HRQoL [14].

According to the average BMI, our patients were overweight, which is consistent with other studies, where participants with OA were overweight or obese [5, 12, 29]. We confirmed that increased BMI was related to poor function, as previously reported, in patients with knee or hip OA [3, 5, 12, 29, 32]. BMI in our study was not related to the physical dimension of HRQoL. Regarding the association between BMI and physical dimension of HRQoL, the findings are controversial [3, 5, 19, 29].

Regarding gender, we noted that female gender was significantly associated with poor function in knee OA, but not in hip OA, and not with the physical dimension of HRQoL. According to the results from previous studies, gender differences in self-reported function and physical dimension of HRQoL in knee or hip OA are controversial [12–14, 18, 21, 32].

For other examined factors (age, comorbidity, duration of symptoms), we did not find associations between these factors and function or physical dimension of HRQoL. In the literature, there is also a disagreement regarding these factors. In contrast to our study, other studies stressed that higher comorbidity was a significant predictor for poor function and poor HRQoL in hip OA [3, 51], but not in knee OA [51].

There are several limitations and strengths of this study. The main limitation is that we did not measure the strength of knee and hip muscles, although a significant association has been reported between the strength of hip and thigh muscles with self-reported function in hip OA [52]. Secondly, all patients were recruited from a single orthopedic clinic, bearing some regional selection bias. However, this orthopedic clinic admits patients from several regions of Serbia, which we believe increases the generalizability of our findings in the studied population. Further, the study included patients with end-stage knee or hip OA; thus the obtained results cannot be generalized to all knee and hip OA patients. Finally, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow us to establish a causal pathway between dependent and independent variables.

The study strength relates to the inclusion of both knee and hip OA patients assessed in a short time period before surgery. In addition, there is little research in which associations among risk factors and function and HRQoL in knee or hip OA were preoperatively evaluated, whereas numerous studies have investigated associations of different preoperative risk factors with postoperative outcome. Further, the use of objective measures of flexion ROM and flexion contracture by one person who is a board-certified specialist of physical and rehabilitation medicine may represent an additional strength. Finally, we had no missing data in questionnaires.

We believe that our results might have important clinical implications for patients with knee and hip OA. Screening for anxiety and pain catastrophizing along with flexion ROM measurement in patients with knee or hip OA should become a part of the assessment. It is important to allocate groups of patients with anxiety and pain catastrophizing and include them in cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques. In addition, flexion ROM could be improved by physical therapy. This might ultimately lead to the preservation of function and better quality of life.

Our findings represent a stimulus for future longitudinal studies to determine the validity of cross-sectional association observed in this study.

Given the facts above, it can be concluded that patients with end-stage knee and hip OA immediately prior to total joint arthroplasty had poor self-reported function and physical dimension of HRQoL, unlike the mental dimension, which was not impaired. Pain catastrophizing and flexion ROM, according to our study, are to a certain degree the most important of all investigated factors associated with poor function and physical dimension of HRQoL in both knee and hip OA.