Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major cause of death all over the world [1, 2]. Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease in the vascular walls [3, 4] that is initiated and progresses via an interplay among multiple factors including proinflammatory cytokines and acute phase proteins such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen [5]. Coronary artery atherosclerosis is a key risk factor in the development of acute coronary syndrome [6].

Among various established clinical and laboratory risk factors associated with the pathogenesis of CVD (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, dyslipidemia and smoking), several lines of evidence have shown that bacterial pathogens may play a main role [1, 4, 7, 8]. Bacterial infections can contribute to CVD mainly through interaction with inflammatory and immunological pathways, either directly or indirectly [1]. Infection has been found to directly impair endothelial function by circulating endotoxins, induce proliferation of smooth muscle cells and local inflammation, and activate the innate immune response [9]. On the other hand, indirect damaging effects of bacterial infections include induction of proinflammatory, hypercoagulability and atherogenic responses, oxidation of low-density lipoprotein, antigen mimicry between bacterial and host cells, induction of nutrient/vitamin malabsorption, and metabolic disruptions such as excess production of ammonia. To sum up, repeated exposure to bacterial infections leads to an excess inflammatory process leading to the provocation of immune responses that adversely affect cardiovascular risk factors such as triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, C-reactive protein, heat shock proteins, cytokines, fibrinogen, and white blood cell count. Different bacterial species related to the risk of CVD include Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumonia and Porphyromonas gingivalis [7–11].

In Iran, a developing country in the Middle East, atherosclerosis is a prevalent disease with a high morbidity and mortality burden [7]. The association between CVD and bacterial infections is not fully known in the Iranian population and some studies have emphasized the existence of a relationship, while others have not found any association. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the possible relationship between main bacterial infections and CVD among Iranian patients using a systematic review and meta-analysis approach.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Search strategy

Up to June 30, 2017, a comprehensive search of publications was performed on the relationship between bacterial infections and CVD in Iran using both Persian- and English-language databases including Scientific Information Database (www.sid.ir), Irandoc (www.irandoc.ac.ir), Iranmedex (www.iranmedex.ir) and Magiran (www.magiran.com) as well as PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, Google Scholar and ISI web of knowledge. The following search terms were selected from the MeSH database: “heart diseases” OR “cardiovascular diseases” OR “coronary artery disease” OR “atherosclerosis” OR “myocardial infarction” OR “ischemic heart disease” AND “bacterial infections” OR “H. pylori” OR “C. pneumonia” OR “P. gingivalis” OR “M. pneumonia” OR “bacterial periodontal diseases” AND “Iran”. Additional related articles were obtained through scanning the reference lists and hand searching. Drafting the systematic reviews and meta-analysis was based on the PRISMA checklist [12].

Study eligibility criteria

After evaluating article titles, abstracts and keywords, case-control studies were selected based on the eligibility criteria including: 1) case-control studies published in Persian and English languages, 2) assessing the relationship between bacterial infections and CVD in Iran, and 3) reporting the prevalence of CVD only in humans. Exclusion criteria were: 1) studies published in other languages, 2) articles except cross-sectional or case-control studies, 3) cross-sectional studies without a control comparator, 4) papers without full text, 5) Persian articles without an English abstract, 6) review articles, 7) duplicate studies, for which only the most recent reports were included, 8) studies presented in conferences as abstracts, 9) assessment of relationships between viral, fungal and parasitic infections with CVD, and 10) evaluated the prevalence rate of bacterial infection and CVD alone.

Data collection process

To reduce possible bias and mistakes, data extraction from each included study was performed by independent authors. Two reviewers extracted data after reviewing the title, abstract and full text of papers and the following information was then extracted and summarized in Table I [13–31]: 1) first author’s surname, 2) year of the study, 3) area (city) of the study, 4) mean age for case and control groups, 5) gender (F/M) ratio for case and control groups, 6) number of patients with different types of CVD, 7) CVD type, 8) type and number of bacterial infections, and 9) bacterial infection detection techniques.

Table I

Profile of selected studies in the meta-analysis

| Author [ref.] | Year | Area | Age [years] | Gender (F/M) | Case group (n) | Control group (n) | Disease type | Type and number of bacterial infections (n) | Infection detection method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | Case | Control | |||||||

| Khodaii et al. [13] | 2010 | Tehran | 53.1 | 48.5 | 240/260 | 250/250 | 500 | 500 | Acute myocardial infarction | H. pylori IgG (330) | H. pylori (100) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Dabiri et al. [14] | 2006–2007 | Tehran | 59 | 45 | 11/22 | 9/22 | 33 | 31 | Atherosclerosis | C. pneumonia PCR (6) DIF (7) | C. pneumonia 0 | PCR DIF |

| Nozari et al. [15] | 2006–2007 | Tehran | 62 | 61 | 27/43 | 29/31 | 70 | 60 | Atherosclerosis | H. pylori (56) | H. pylori (39) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Davoudi et al.[16] | 2006–2007 | Tehran | 60.5 | 57.57 | 16/53 | 39/45 | 69 | 84 | Atherosclerosis | H. pylori (40) | H. pylori (48) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Bahrmand et al. [17] | 2001 | Tehran | NA | NA | 20/34 | NA | 54 | 24 | Atherosclerosis | C. pneumonia PCR (14) IgA (10) IgG (39) | C. pneumonia 0 | PCR MIF |

| Rogha et al. [18] | 2010–2011 | Isfahan | 62.4 | 59.05 | 20/42 | 17/26 | 62 | 43 | Atherosclerosis | H. pylori (30) | H. pylori (16) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Ashtari et al. [19] | 2005–2006 | Isfahan | 68.71 | 66.01 | 19/23 | 48/34 | 42 | 82 | Atherosclerosis | C. pneumonia IgA (7) IgG (11) | C. pneumonia IgA (5) IgG (15) | Serologic test (IgA IgG) |

| Sarraf-Zadegan et al. [7] | 1998–1999 | Isfahan | 55 | 50.8 | 15/37 | 15/40 | 52 | 55 | Acute myocardial infarction | H. pylori (36) | H. pylori (8) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Sadeghian et al. [20] | 2010 | Mashhad | 32 | NA | 5/25 | NA | 30 | 30 | Atherosclerosis | C. pneumonia (1) | C. pneumonia 0 | PCR |

| Assar et al. [21] | 2010–2011 | Bandarabbas | 61 | 62.35 | 43/42 | 44/41 | 85 | 85 | Atherosclerosis | C. pneumonia (25) | C. pneumonia (5) | PCR |

| Vafaeimanesh et al. [22] | 2013 | Qom | 57.9 | 53.1 | 27/35 | 32/26 | 62 | 58 | Atherosclerosis | H. pylori (46) | H. pylori (30) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Azarkar et al. [23] | 2011 | Birjand | 59.8 | 56.4 | 20/53 | 29/49 | 73 | 78 | Acute myocardial infarction | H. pylori IgA (31) IgG (42) | H. pylori IgA (38) IgG (25) | Serologic test (IgA IgG) |

| Jafarzadeh et al. [24] | 2007–2008 | Rafsanjan | 55.2 | 52.9 | 46/74 | 27/33 | 120 | 60 | Acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina | H. pylori (107) | H. pylori (35) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Karimi et al. [25] | 2003–2004 | Rafsanjan | 52 | 52 | 22/36 | 11/18 | 58 | 29 | Acute myocardial infarction and chronic stable angina | C. pneumonia (48) | C. pneumonia (9) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Nejad et al. [6] | 2013 | Qazvin | 58.57 | 57.98 | 33/57 | 29/61 | 90 | 90 | Acute myocardial infarction | H. pylori (IgA: 48 IgG: 84) M. pneumonia (IgG: 69) | H. pylori (IgA: 61 IgG:76) M. pneumonia (IgG: 63) | Serologic test (IgA IgG) |

| Iranpour et al. [26] | 2014 | Bushehr | 65.3 | 61.6 | 19/71 | 49/41 | 90 | 90 | Atherosclerosis | C. pneumonia (9) | C. pneumonia (6) | Serologic test (IgM IgG) |

| Zibaeenezhad et al. [27] | 2002 | Shiraz | 57.4 | 50 | 41/68 | 40/18 | 109 | 58 | Atherosclerosis | C. pneumonia (93) | C. pneumonia (43) | Serologic test (IgA IgG) |

| Pourahmad et al. [28] | 2005–2007 | Jahrom | 62.29 | 61.71 | 14/31 | 21/24 | 45 | 45 | Acute myocardial infarction | M. pneumonia (21) | M. pneumonia (11) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Alavi et al. [29] | 2004–2005 | Ahwaz | 56.48 | 58.03 | 53/43 | 50/46 | 96 | 96 | Unstable angina | H. pylori (79) | H. pylori (55) | Serologic test (IgG) |

| Ansari et al. [30] | 2010 | Tabriz | 55 | 26 | 91/9 | 77/12 | 100 | 89 | Atherosclerosis | H. pylori (68) | H. pylori (44) | Serologic test (IgG) |

Data synthesis

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software version 2.2 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) was used for statistical analysis and the association between bacterial infections and CVD was expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Risk of publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s and Egger’s tests. Existence of heterogeneity across studies was determined using the Cochrane Q test and the inconsistency index (I2). In the case of small and large heterogeneity, fixed- and random-effects models were used to pool the results. In all analyses, p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

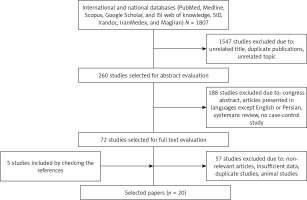

As shown in the flow diagram, a total of 20 case-control studies were obtained on the relationship between different bacterial infections and CVD in Iran up to June 30, 2017. Briefly, 1807 original articles were collected from various national and international databases. After title, abstract and full text screening, 1792 articles were omitted based on exclusion criteria. Five articles were included after assessing the references and the meta-analysis was performed on 20 selected articles. Several papers were excluded because they had no effect on meta-analysis results. These selected papers were from Tehran (5 studies), Isfahan (3 studies), Rafsanjan (2 studies), and Mashhad, Tabriz, Shiraz, Ahwaz, Qazvin, Qom, Bandar Abbas, Bushehr, Birjand, and Jahrom (each with 1 study) (Figure 1). Profiles of selected studies in the meta-analysis are listed in Table I [13–30]. Serological tests were the most important techniques used for the diagnosis of bacterial infections in patients with CVD in Iran. The most common type of CVD was atherosclerotic CVD.

The association between C. pneumonia infection and CVD

In Iran, a total of 8 relevant studies evaluated the association between C. pneumonia infection and CVD (Table I). Molecular and serological methods were the most important diagnostic tests for the detection of C. pneumonia infection. Based on PCR, IgG and IgA tests, C. pneumonia infection prevalence in case groups was 22.7% (46/202), 56.6% (200/353), and 53.6% (110/205), respectively. However, in control groups, the positive rate of C. pneumonia infection on the basis of PCR, IgG and IgA tests was 2.9% (5/172), 25.7% (73/283), and 29.2% (48/164), respectively. Odds ratios for the association between C. pneumonia infection and CVD based on PCR, IgG and IgA tests were 7.420 (95% CI: 3.088–17.827), 3.710 (95% CI: 1.361–10.115) and 2.492 (95% CI: 1.305–4.756), respectively (Figure 2).

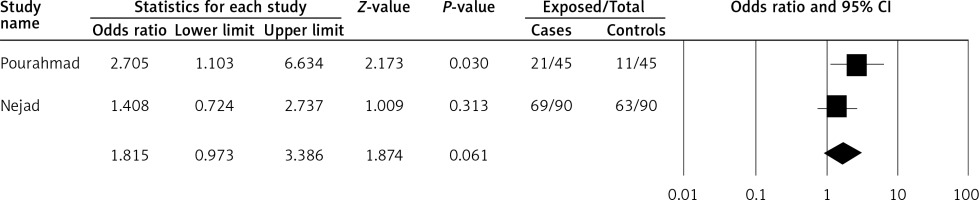

Figure 2

Forest plot of C. pneumonia infection associated with heart disease risk in Iran. A – PCR, B – IgG, C – IgA-based tests

There was low heterogeneity of the included studies; therefore, we used a fixed-effect model for assessing the association between C. pneumonia infection and CVD on the basis of PCR (p = 0.829, I2 = 0%) and IgA (p = 0.480, I2 = 0%). However, based on the IgG test (p = 0.002, I2 = 75.7%), a random-effects model was used to demonstrate the association between infection and disease. As shown in Table II, Begg’s and Egger’s tests were used to evaluate publication bias of studies.

Table II

Publication bias results based on Begg’s and Egger’s tests

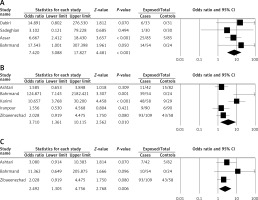

The association between M. pneumonia infection and CVD

There were only 2 studies evaluating the association between M. pneumonia infections and CVD in Iran. IgG-based serologic testing was the only method used to detect M. pneumonia infection (Table I). In the present study, the prevalence rate of M. pneumonia infection on the basis of the IgG test in case and control groups was 66.6% (90/135) and 54.8% (74/135), respectively. Moreover, the calculated odds ratio for M. pneumonia infection was 1.815 (95% CI: 0.973–3.386).

A fixed-effect model was applied, due to low heterogeneity (p = 0.252, I2 = 23.7%), to pool results and to evaluate the association between M. pneumonia infection and CVD on the basis of IgG (Figure 3).

The association between H. pylori infection and CVD

As shown in Table I, using serologic tests, the association between H. pylori infection and CVD was assessed in 10 articles in Iran. Based on IgG, the prevalence of H. pylori infection among case and control groups was 70.9% (918/1294) and 39.2% (476/1213), respectively. Furthermore, the calculated odds ratio was 3.160 (95% CI: 1.957–5.102) (Figure 4 A). Based on IgA, the prevalence of H. pylori infection was 48.4% (79/163) for case groups and 58.9% (99/168) for control groups. The calculated odds ratio for H. pylori infection was 0.643 (95% CI: 0.414–0.999) (Figure 4 B).

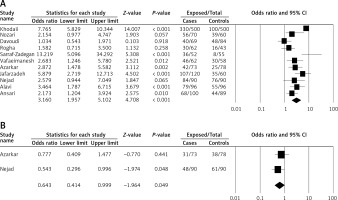

Figure 4

Forest plot of H. pylori infections associated with heart disease risk in Iran. A – IgG, B – IgA-based tests

Finally, to pool the results of the IgG-based H. pylori test (p < 0.001, I2 = 83%), a random-effects model was used, and for the IgA-based H. pylori test (p = 0.427, I2 = 0%), a fixed-effect model was used.

Discussion

The risk factors for the emergence and development of CVD are not the same in different patients [15]. More than a century ago, potential roles of infectious organisms including bacteria and viruses as potent risk factors in the induction of heart diseases were investigated in several epidemiological studies [31]. Chlamydia pneumonia, a Gram-negative and obligate intracellular bacterium, was the first proposed etiologic agent responsible for the induction of inflammation in the vessel walls of patients with CVD [31, 32]. In Iran, the prevalence of C. pneumonia infection in patients with CVD is rather high [14]. However, there are confusing results about the role of C. pneumonia in the pathogenesis of the disease in Iran and the world. For example, Sadeghian et al. [20], Zibaeenezhad et al. [27], West et al. [33] and Apfalter et al. [34] did not find a link between C. pneumonia infection and CVD, while Dabiri et al. [14], and Sessa et al. [35] found a significant correlation. These differences in results may be due to the variations in sampling, population size, applied detection technique, ethnicity, region, and disease type [21]. In the present study, the prevalence of C. pneumonia infection was higher in case groups compared with control groups, as detected by PCR, IgG and IgA tests (Figures 2 A–C). In addition, our findings showed that the detection rate of C. pneumonia using molecular methods was lower than the serological methods in both case (22.7% vs. 56.6% and 53.6%) and control groups (2.9% vs. 25.7% and 29.2%). Based on the molecular detection methods, the prevalence of C. pneumonia among Iranian subjects with CVD (22.7%) was higher than in India (10%) [36] and Turkey (15%) [37], and lower than in Poland (27%) [38] and Japan (62%) [39]. Our results support the notion that there is a significant association between C. pneumonia and CVD risk in the Iranian people.

Helicobater pylori, a Gram-negative and microaerophilic bacterium, colonizes the stomach of approximately 50% of the world’s population and is involved in gastritis, peptic ulcer, adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma [40–42]. There is inconsistent evidence on the association between H. pylori infection and CVD risk in Iran. Khodaii et al. [13] reported a significant association between H. pylori infection and CVD. In contrast, no association was found between H. pylori infection and CVD in a study reported by Eskandarian et al. [43]. In the present meta-analysis, we found a significant correlation between H. pylori infection and CVD risk in Iran based on the IgG test (OR = 3.160, p < 0.001). However, there was no relationship between H. pylori infection and CVD based on the IgA test (OR = 0.643, p = 0.049). One reason for this inconsistency could be the low number of studies in the latter category (n = 2). Two studies from Poland and Germany showed a significant association between H. pylori infection (detected according to genotypic and serological methods, respectively) and CVD risk [38, 44]. In contrast, one study from Austria did not suggest a main role for H. pylori infection in CVD [45]. The existence of these conflicting results suggests that the use of highly sensitive and specific methods is necessary to confirm the hypothetical relationship between infectious agents and the development of CVD.

In recent studies, it was suggested that the smallest pathogenic cause of atypical pneumonia in human is M. pneumonia, which is a common respiratory tract microorganism related to CVD risk either alone or along with other risk factors [46]. However, in Iran, only 2 studies assessed this possible risk using serological tests (Table I). In the present study, the obtained odds ratio for M. pneumonia infection among case groups with CVD was 1.815. It suggests that M. pneumonia infection may be a risk factor for CVD. Similar finding were reported in Saudi Arabia [46], Japan [47], the Netherlands [48] and Germany [44]. Inconsistently with our results, the role of M. pneumonia infection in the etiopathogenesis of CVD has been refuted in some studies [38, 45]. Various sensitivity and specificity values for different diagnostic tests for detecting M. pneumonia infection in patients with CVD may be an important reason for discrepancies in the results obtained in different studies [48]. In this meta-analysis, no study was found on the association between P. gingivalis infection and resulting bacterial periodontal infections and CVD risk in Iran. Finally, we recommend evaluation of the association between cardiovascular risk factors and biomarkers such as plasma low- and high-density lipoprotein (LDL and HDL) and vitamin D status with various bacterial infections that predispose to CVD [49–51].

In conclusion, the present systematic review focused on the association between different bacterial infections and CVD risk in Iran. Our meta-analysis revealed that H. pylori, C. pneumonia and M. pneumonia infections could be considered as potential risk factors for CVD in Iran. These findings are worthwhile to confirm the role of bacterial infections as predisposing factors for CVD and also explore the bacterial species that have a stronger association with CVD. Based on the present findings, efficient and timely eradication of H. pylori, C. pneumonia and M. pneumonia infections could be a useful strategy to reduce the burden of CVD. This study was limited in several ways including heterogeneity of diagnostic tests used for the detection of infections, and lack of a complete spectrum of studied bacterial species in relation to CVD. Furthermore, our analysis was limited to Iran, and a global investigation will be crucial for generalization of the findings. Based on the mentioned limitations, additional studies are needed to explain the difference between obtained results on the basis of various bacterial infection detection methods. Finally, the association between other bacterial infections and CVD risk in Iran merits further investigations.