Introduction

Hypertension is a major cause of deaths and morbidity around the world [1–4]. Prior observational studies have demonstrated that increased clinic blood pressure (BP) is independently associated with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality [1, 5, 6]. Importantly and interestingly, in the last decade, observational studies have revealed that some individuals have normal BP in the outpatient clinic but with increased BP outside of the clinic office, which is now known as masked hypertension [7–10].

Accumulating evidence has shown a high prevalence of masked hypertension in both treated and untreated hypertensive patients [11–14]. However, cardiovascular risk of masked hypertension is unclear and needs further elucidation. For example, some, but not all, studies reported that masked hypertension was independently associated with higher incidence of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality [15, 16]. However, other studies did not observe such an association after adjustment for traditional risk factors [17, 18]. The discrepancies between these studies might be due to differences in study design, population characteristics, BP measurement methods and masked hypertension definition. In addition, most of the prior studies were conducted in United States and European populations, and the association between masked hypertension and cardiovascular risk in Chinese populations is unknown.

Therefore, in our current cross-sectional study, patients with primary hypertension from our outpatient clinic were enrolled. Thwenty-four hours ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) was performed to diagnose masked hypertension based on the guideline recommendation [19]. The aim of our current study was to evaluate the association of masked uncontrolled hypertension (MUCH) and the prevalence of cardiovascular disease in China’s hypertensive patients. Hopefully, data from our current study will provide a foundation for future studies to further investigate whether treatment of MUCH could improve cardiovascular outcomes in these patients.

Material and methods

Participants’ enrollment

Patients with primary hypertension in our outpatient clinic were enrolled after informed consent was obtained and patients were seen and enrolled in the general cardiologic clinic. Our current study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethical Committee of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age 50–75 years, and patients were able to perform daily activity during 24 h ABPM measurement. The exclusion criteria were as follows: newly diagnostic hypertension, secondary hypertension, had myocardial infarction, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke in past 12 months, had exacerbated congestive heart failure in past 3 months, had chronic kidney disease (CKD) ≥ stage 3, or could not ambulatory voluntarily during 24 h ABPM measurement or could not finish 24 h ABPM measurement.

Data collection

Demographics and prior medical histories were extracted from the electronic health record in the outpatient clinic system. Fasting venous blood was drawn for evaluation of fasting blood glucose (FBG), uric acid (UA), total cholesterol (TC), and creatinine level. In specific, serum creatinine level was used to calculate glomerular filtration rate (GFR) based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula [20] and GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 was considered as CKD ≥ stage 3.

Clinic BP and 24 h ABPM measurements

Clinic BP measurements were performed based on the JNC 7 guideline recommendation [21]. Specifically, no smoking or caffeine-containing beverages were allowed before clinic BP measurement. In addition, no anti-hypertensive medications were allowed before the clinic visit. Patients sat quietly for 10 min with the back supported and the appropriate cuff size was used with the bladder encircling at least 80% of the non-dominant arm (Omron HEM-8731, Tokyo, Japan). The patient’s arm was placed on the desk at heart level. Three readings with a 1-minute interval between measurements were performed and the last two readings were averaged as clinic BP. 24 h ABPM measurement was performed based on the European Society Hypertension practice guideline recommendation (Spacelabs 90217, Spacelabs Inc, Redmond, Wash) [19]. Daytime and nighttime intervals were determined using sleep time reported by patients’ diary cards. At least 20 valid awake and 7 valid asleep measurements should be recorded. Based on the guideline recommendation [19], the definition of MUCH in our current study was clinic BP < 140/90 mm Hg and daytime BP > 135/85 mm Hg.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and between-group differences were analyzed by Student’s t test. Categorical variables were expressed as number and percentage of cases, and between-group differences were analyzed by χ2 analysis or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between MUCH and the composite of cardiovascular disease including coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke and chronic heart failure. Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics comparison

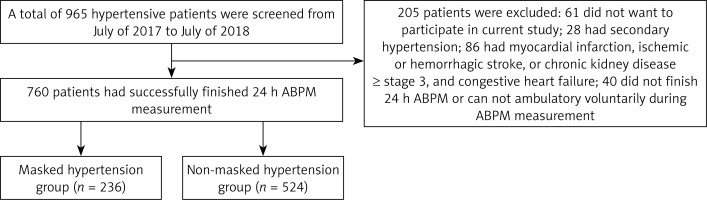

A total of 965 hypertensive patients were screened from July of 2017 to July of 2018, and finally 760 patients were enrolled (Figure 1), and among them 4 patients had prior ABPM which was conducted in the past 2 years. Based on the clinic BP and 24 h ABPM results, patients were divided into MUCH and non-masked hypertension groups. Between-group differences were evaluated. As shown in Table I, compared to patients without masked hypertension, patients with MUCH were more likely to be older, male and diabetic, have longer duration of hypertension and lower GFR, and be treated with a β-blocker, and required more antihypertensive medications, and had higher prevalence of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke. These findings suggested that patients with MUCH had more comorbidities than those without masked hypertension.

Table I

Baseline characteristics comparison

| Parameter | MUCH (n = 236) | Non-masked hypertension (n = 524) |

|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 62.4 ±11.2 | 59.7 ±10.4* |

| Male, n (%) | 158 (66.9) | 332 (63.4)* |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 80 (34.7) | 180 (34.3) |

| Hypertension duration [years] | 12.4 ±5.3 | 9.5 ±4.5* |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 80 (33.9) | 155 (29.6)* |

| Total cholesterol [mmol/l] | 5.3 ±0.7 | 5.3 ±0.6 |

| Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/l] | 6.1 ±0.6 | 6.0 ±0.6 |

| Uric acid [µmol/l] | 366 ±50 | 324 ±42* |

| Creatinine [µmol/l] | 80.2 ±25.3 | 78.6 ±22.9 |

| Glomerular filtration rate [ml/min/1.73 m2] | 79.5 ±11.6 | 82.4 ±10.3* |

| Antiplatelet drugs, n (%) | 172 (72.9) | 386 (73.7) |

| Statin, n (%) | 130 (55.1) | 294 (56.1) |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 167 (70.8) | 367 (70.0) |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 92 (39.0) | 172 (32.7)* |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 100 (42.4) | 225 (42.9) |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 45 (19.1) | 90 (17.2) |

| Number of antihypertensive medications | 2.7 ±0.5 | 2.2 ±0.3* |

| Anti-diabetic drugs, n (%) | 66 (28.0) | 152 (29.0) |

| Insulin, n (%) | 10 (4.2) | 15 (2.9) |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 29 (12.3) | 45 (8.6)* |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 32 (13.6) | 58 (11.0)* |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 10 (4.2) | 20 (3.8) |

Clinic BP and 24 h ABPM comparison

As presented in Table II, no significant differences in clinic BP were observed between MUCH and non-masked hypertension groups. However, compared to the non-masked hypertension group, patients with MUCH had significantly higher 24 h systolic BP (135 ±10 mm Hg vs. 128 ±8 mm Hg), daytime systolic BP (142 ± 6 mm Hg vs. 130 ±4 mm Hg) and diastolic BP (89 ±4 mm Hg vs. 78 ±6 mm Hg). These findings suggested that patients with MUCH had higher out-of-clinic BP, especially during the daytime period.

Table II

Clinic BP and 24 h ABPM comparison

| Variables | MUCH (n = 236) | Non-masked hypertension (n = 524) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinic systolic BP [mm Hg] | 126 ±9 | 125 ±12 |

| Clinic diastolic BP [mm Hg] | 67 ±10 | 68 ±9 |

| Clinic heart rate [beat per minute] | 70 ±14 | 73 ±9 |

| 24 h systolic BP [mm Hg] | 135 ±10 | 128 ±6* |

| 24 h diastolic BP [mm Hg] | 72 ±8 | 68 ±8 |

| 24 heart rate [beat per minute] | 74 ±10 | 70 ±12 |

| Daytime SBP [mm Hg] | 141 ±6 | 130 ±4* |

| Daytime DBP [mm Hg] | 89 ±4 | 78 ±6* |

| Daytime heart rate [beats per minute] | 82 ±10 | 75 ±9* |

| Nighttime SBP [mm Hg] | 130 ±6 | 126 ±7 |

| Nighttime DBP [mm Hg] | 68 ±7 | 64 ±5 |

| Nighttime heart rate [beat per minute] | 69 ±6 | 66 ±5 |

Association of masked hypertension and cardiovascular disease

Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association of MUCH and cardiovascular disease. As shown in Table III, in the unadjusted model, the odds ratio (OR) of masked hypertension for cardiovascular disease was 2.32. With stepwise regression analysis, even after adjustment for potential confounding factors from demographics, comorbidities, medications used and clinic BP, MUCH was still independently associated with cardiovascular disease, with OR of 1.38 and 95% confidence interval of 1.17–1.62. These findings indicate that MUCH might increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in treated hypertensive patients.

Table III

Association of masked uncontrolled hypertension and cardiovascular disease

| Unadjusted | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

| 2.32 (1.96–2.97) | 2.02 (1.69–2.62) | 1.85 (1.45–2.34) | 1.63 (1.29–2.08) | 1.38 (1.17–1.62) |

[i] Model 1 – adjusted for age and male gender, model 2 – adjusted for model 1 + current smoker, hypertension duration, diabetes mellitus, total cholesterol, uric acid and GFR, model 3 – adjusted for model 1 + model 2 + antiplatelet, statin, antihypertensive medications, anti-diabetic medications, model 4 – adjusted for model 1 + model 2 + model 3 + clinic BP.

Discussion

Data from our current study show that the prevalence of MUCH in treated hypertensive patients is not low, and compared to patients without masked hypertension, those with MUCH have a significantly higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, MUCH is still independently associated with prevalent cardiovascular disease.

It is well known that the diagnosis of hypertension is traditionally defined by the clinic BP [22–24]. Prior randomized clinical trials and meta-analysis have consistently demonstrated that reducing clinic BP can improve cardiovascular outcomes [25–29]. With the advent and advancement of 24 h ABPM, out-of-clinic BP can be captured and used for evaluating daytime and nighttime BP changes [30, 31]. Interestingly and importantly, accumulating evidence shows that a substantial proportion of patients with controlled clinic BP have increased BP at home, which is now named masked hypertension. Furthermore, observational studies have also indicated that those with masked hypertension have higher cardiovascular risk than those without masked hypertension [17]. However, some other studies did not observe such an association after adjustment for potential confounding factors [32]. Recently, one systemic review and meta-analysis indicated that in 30 352 treated hypertensive patients with normal clinic BP, risks of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality were higher in those with MUCH [33], which was defined by the same criteria as those used in our current study. Consistent with the recent published systemic review and meta-analysis [33], our current study also showed that in treated Chinese hypertensive patients, compared to those without masked hypertension, patient with MUCH had a higher absolute and relative risk of prevalent cardiovascular diseases. Findings from our current study support the notion that a future randomized clinical trial should be conducted to evaluate whether improvement of out-of-clinic BP could further reduce cardiovascular risk in MUCH patients [34].

In one large population study, Banegas et al. reported that from 62 788 patients with treated BP in the Spanish registry, nearly 31.1% had MUCH [35]. Interestingly, in our current study, we also observed that the prevalence of MUCH in Chinese treated hypertensive patients was nearly 31%. However, in a prior study the authors used 24 h BP as diagnostic criteria versus daytime BP as diagnostic criteria in our current study.

Notably, as presented in Table II, we observed that the clinic BP in both groups was similar. However, compared to patients without masked hypertension, those with MUCH had significant higher 24 h systolic BP, daytime systolic BP and daytime diastolic BP, which might be due to higher sympathetic output in these populations [31, 35]. Indeed, the daytime HR was significantly higher in the MUCH group versus the non-masked hypertension group. Interestingly, although nighttime BP was also higher in the MUCH group, these differences did not achieve statistical significance. Previously some studies indicated that one of the potential mechanisms related to MUCH was increased sympathetic output during sleep [31, 35]. However, findings from our current study did not support this hypothesis. Future studies are needed to further corroborate our current findings.

Compared to non-masked hypertension, we found that patients with MUCH had more co-morbidities at baseline. Due to our cross-sectional design, we were unsure whether masked hypertension contributed to these co-morbid conditions or vice versa. Nevertheless, data from our current study provide insight into the relationship between MUCH and prevalent cardiovascular disease in Chinese treated hypertensive patients.

The definition of masked hypertension used in our current study is based on the ESH/ESC consensus, which is also consistent with a recent published meta-analysis [31, 35]. Therefore, we considered that future studies in both Chinese hypertensive patients and other ethnic populations can use the same definition to corroborate our current findings. Since our current study was an observational study, we have no idea whether the findings from our current study could influence the treatment strategies in the future. However, in line with accumulating evidence, one may anticipate that treatment for correcting masked hypertension may be beneficial to improve cardiovascular outcomes.

One important thing that needs to be addressed is that in our current study, we measured clinic BP based on the JNC 7 recommendation. However, some differences between clinic BP measurements were noted between the JNC 7 and the new 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension guideline [36]. Therefore, we were unsure whether the used BP measurement approach recommended by the new guideline would influence our current findings or not. In addition, the new guideline used 130/80 to define hypertension, which was different from our current study. Regarding the lower diagnostic threshold of clinic BP, one may speculate that the prevalence of masked hypertension might be higher, and the odds of MUCH and prevalent cardiovascular disease might be increased. However, the protocol of our current study was designed before the new guideline was released and China’s Hypertension Committee continued to use 140/90 for diagnostic criteria [37]. Therefore, future studies are needed to corroborate our current finding using the new recommended approach to measure clinic BP.

There are some limitations of our current study that need to be addressed. First, the cross-sectional and observational design did not allow us to infer a causal relationship between MUCH and cardiovascular diseases. Second, despite adjustment for potential confounding factors in the regression model, undetected and unmeasured biases could still exist which in turn could influence the association between MUCH and cardiovascular disease. Third, since participants were enrolled from China, findings from our current study could not be extrapolated to other ethnic groups. Last but not least, BP measurement and hypertension diagnostic criteria in our current were based on the JNC 7 guideline recommendation, which was also consistent with China’s Hypertension guideline [37]. We were unsure whether the findings of our current study could be replicated if BP measurement and hypertension diagnostic criteria were evaluated using the new ACC/AHA hypertension guideline. A future study is needed to validate our findings.

In conclusion, our current study indicates that in China’s treated hypertensive patients, MUCH is associated with higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease. Future studies are needed to evaluate whether improvement of masked hypertension could confer cardiovascular benefits to these patients.