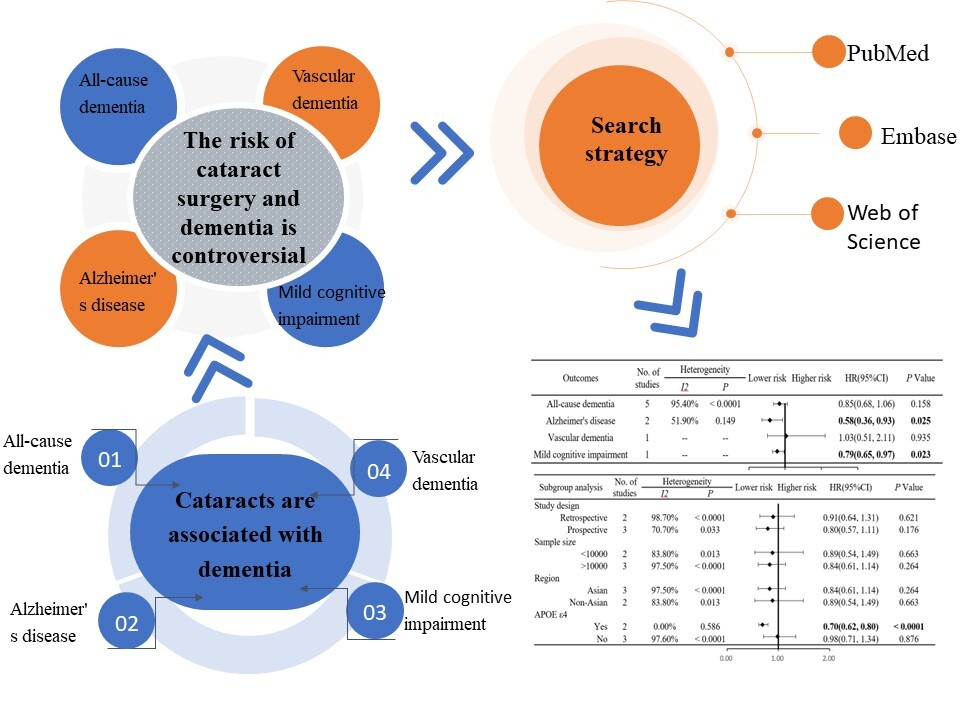

The treatment options for dementia patients remain limited in their efficacy. Consequently, there has been a growing research focus on identifying risk factors that could potentially prevent or delay the onset of dementia. Visual impairment has been recognized as a significant risk factor for dementia [1–3]. Cataract is the most prevalent reversible cause of blindness, and it is typically treated through surgical intervention to restore vision [4, 5]. Numerous studies [6–10] have investigated the association between cataract surgery and dementia. However, the impact of cataract surgery on the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease remains controversial. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of existing literature on cataract surgery and its association with dementia, with the aim of providing a scientific foundation for strategies to prevent or delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Methods

Search strategy The PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases from inception to March 31, 2024 were extensively searched for cohort studies on cataract surgery and dementia.

Inclusion criteria

(1). Study design: Cohort study; (2). Participant: Cataract patient; (3). Intervention: The observation group received cataract surgery, while the control group did not receive cataract surgery; (4) Outcomes: The primary outcome was all-cause dementia. Secondary outcomes were other types of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, etc.; (5). Effect size: relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), and hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Exclusion criteria

(1) Non-English literature; (2) Review literature or case studies; (3) Data missing, or unable to extract, or the full text of the literature not available; (4) Republished literature.

Data extraction

When screening articles, we first read the title to eliminate irrelevant ones, and then further reviewed the abstract and full text to determine whether to include the article. The data collected were collated and analyzed independently by two researchers using Excel 2021. The extracted information included the first author, year of publication, region, data source, study design, sample size, type of dementia, cataract diagnosis, dementia diagnosis, follow-up time, age, outcome, effect size, 95% CI, and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) score. We cross-examined the findings, and in the event of a dispute, discussed the resolution or consulted a third researcher.

Study quality assessment

NOS was used to evaluate the quality of included studies [11]. An NOS score ≥ 7 was considered to be of high quality.

Data synthesis and analysis

HR and 95%CI were calculated using Stata14.0 software. I2 values were used to detect the heterogeneity between included studies. If p > 0.1 and I2 < 50%, there was no statistical heterogeneity, and a fixed effect model was used for analysis. If p < 0.1 and I2 ≥ 50%, there was statistical heterogeneity, and a random effects model was used for analysis. Subgroup analyses were performed based on study design (retrospective vs. prospective), sample size (< 10,000 vs. > 10,000), region (Asian vs. non-Asian), and whether to adjust for APOE ε4 mutations (yes vs. no). The funnel plot method was used to analyze whether publication bias existed. Finally, sensitivity analysis was used to verify the stability of the results.

Results

Study characteristics

The number of items of literature preliminarily obtained through database retrieval was 462. After a thorough screening and careful review, five articles [6–10] were finally included for meta-analysis, involving 720,075 participants (Figure 1 A). The basic characteristics of the literature are presented in Table I.

Table I

Basic characteristics of included studies

Figure 1

A – Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flowchart of included studies; B – Forest plot of association between cataract surgery and dementia risk; C – Forest plot of subgroup analysis of cataract surgery and the risk of all-cause dementia; D – Sensitivity analysis for the association between cataract surgery and the risk of all-cause dementia; E – Forest plot of subgroup analysis of cataract surgery and the risk of all-cause dementia (after excluding Lee et al. 2023)

Meta-analysis results

Meta-analysis showed that cataract surgery was not associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia (HR = 0.85, 95% CI (0.68, 1.06), p = 0.158) (Figure 1 B). However, it was associated with a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (HR = 0.58, 95% CI (0.36, 0.93), p = 0.025) (Figure 1 B). Descriptive analysis revealed that cataract surgery did not correlate with a reduced risk of vascular dementia (HR = 1.03, 95% CI (0.51, 2.11), p = 0.935) (Figure 1 B), but it was associated with a lower risk of mild cognitive impairment (HR = 0.79, 95% CI (0.65, 0.97), p = 0.023) (Figure 1 B).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed based on study design (retrospective vs. prospective). Subgroup analyses showed that cataract surgery was not associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia, regardless of whether the study design was prospective or retrospective (retrospective: HR = 0.91, 95% CI (0.64, 1.31), p = 0.621; prospective: HR = 0.80, 95% CI (0.57, 1.11), p = 0.176) (Figure 1 C).

Subgroup analysis was performed according to the study sample size (< 10,000 vs. > 10,000). Subgroup analyses showed that cataract surgery was not associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia, regardless of sample size < 10,000 or > 10,000 (< 10,000: HR = 0.89, 95% CI (0.54, 1.49), p = 0.663; > 10,000: HR = 0.84, 95% CI (0.61, 1.14), p = 0.264) (Figure 1 C).

Subgroup analysis was performed by region (Asian vs. non-Asian). Subgroup analyses showed that cataract surgery was not associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia, regardless of region being Asian or non-Asian (Asian: HR = 0.84, 95% CI (0.61, 1.14), p = 0.264; non-Asian: HR = 0.89, 95% CI (0.54, 1.49), p = 0.663) (Figure 1 C).

Subgroup analyses were performed based on whether the included studies adjusted for APOE ε4 mutations (yes vs. no). Subgroup analyses showed that after adjusting for APOE ε4 mutations, cataract surgery was associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia (HR = 0.70, 95% CI (0.62, 0.80), p < 0.0001) (Figure 1 C). However, without adjusting for APOE ε4 mutations, cataract surgery was not associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia (HR = 0.98, 95% CI (0.71, 1.34), p = 0.876) (Figure 1 C).

Sensitivity analysis

The included literature was excluded item by item for sensitivity analysis. When the study by Lee et al. (2023) [6] was excluded, the meta-analysis results showed statistical significance (Figures 1 D, E).

Discussion

Our meta-analysis of existing studies showed that cataract surgery was not associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia, but it was associated with a decreased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. The results of this meta-analysis are quite different from those of previous meta-analyses. Previous meta-analyses suggested that cataract surgery might help reduce the risk of all-cause dementia [12–14]. First, Liu et al.’s [12] meta-analysis pooled various types of dementia and found that cataract surgery was associated with a reduced risk of dementia. Additionally, a meta-analysis by Zhang et al. [13] found that cataract surgery was associated with a lower incidence of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, Yeo et al.’s [14] meta-analysis focused solely on all-cause dementia. Our study incorporated the most recent literature and conducted a meta-analysis of multiple types of dementia, building on the findings of these three previous meta-analyses. This approach allowed us to more thoroughly assess the relationship between cataract surgery and dementia risk. Compared to earlier studies, our research is innovative in several ways. First, our meta-analysis included the latest literature and increased the sample size, enhancing the reliability and credibility of the findings. Second, we analyzed different types of dementia, rather than aggregating the results of different types. Finally, to explore the potential influencing factors, we conducted subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis, which were not addressed in previous meta-analyses.

Results from a meta-analysis of five cohort studies included in this research indicated that cataract surgery was not associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia in cataract patients. After excluding the study by Lee et al. [6], it was found that cataract surgery was indeed associated with a reduced risk of all-cause dementia in cataract patients. This was consistent with the results of previous meta-analyses [12–14]. We hypothesize that this discrepancy may be due to the inclusion of other eye diseases, such as glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and age-related macular degeneration, in the multifactorial analysis, as these conditions are known risk factors for dementia and cognitive impairment. Overall, cataract surgery is associated with a lower risk of dementia in cataract patients. The APOEε4 mutation is the most important genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease [15–17]. In this meta-analysis, a subgroup analysis was performed to determine whether APOEε4 mutations were adjusted. We found that after adjusting for APOEε4 mutations in two studies [7, 8], cataract surgery was associated with a significantly reduced risk of all-cause dementia in cataract patients. Meanwhile, a meta-analysis that included the same two studies [7, 8] found that cataract surgery was associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease in cataract patients. Therefore, this study strongly supports the conclusion that cataract surgery can help reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in cataract patients.

Cataract is a treatable visual impairment of the eye [18]. Visual impairment may increase the risk of dementia and cognitive impairment [3, 19, 20]. Early prevention and timely treatment of visual impairment can reduce the incidence of dementia [21]. Surgery can significantly reduce the risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in cataract patients. Researchers have analyzed the mechanisms of cataract surgery and reduced dementia risk. First, after cataract surgery, people can receive higher-quality sensory input, which may help mitigate the risk of dementia [6]. Second, cataract surgery reactivates cells that are sensitive to blue light. A specific group of cells in the retina, known as intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGC), are particularly sensitive to blue light stimulation and play a crucial role in regulating circadian rhythms [22, 23]. Degeneration and functional alterations in these cells have been shown to be associated with cognition and Alzheimer’s disease [23–25]. Because cataract surgery restores the passage of blue light through the lens into the ipRGC, it reactivates these cells to prevent cognitive decline [7].

Limitations of this study. First, it was a cohort-based analysis, and the adjusted covariates in the results varied, which may introduce potential confounding factors. Consequently, the influence of other variables on dementia risk cannot be entirely ruled out. Second, the study was based on observational data, and randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the association between cataract surgery and dementia risk. Third, due to the limited number of included studies, there might be potential publication bias. Fourth, the included studies only compared cataract patients who underwent surgery with those who did not. Fifth, while the number of participants in the study was substantial, it may not be representative of the broader population. Participants may be from specific regions or specific medical institutions, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, cognitive impairment and dementia are complex conditions influenced by various factors, including genetics, vascular disease, and inflammation. Therefore, it is unclear whether cataract surgery directly causes dementia or if other mediating variables are involved. As a result, the question of whether cataracts represent an independent risk factor for dementia requires further investigation.

In conclusions, the available evidence suggests that cataract surgery may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in cataract patients. However, the relationship between cataract surgery and the reduced risk of all-cause dementia in these patients requires further investigation. The study had several limitations, including its observational design, potential confounding factors, limitations in sample characteristics, and inability to determine causation. Future studies will need to employ more rigorous study designs and explore specific mechanisms to further validate this association and provide more robust evidence.