The successful development of a drug testing platform having human skin bioequivalence would accelerate discoveries in several research fields, with significant real-world applications. Traditional in vitro methods for compound analysis have relied on two-dimensional (2D) cell-based assays [1]. While 2D cultures are a relatively simple and low-cost method enabling high throughput screening of large compound libraries [2], they do not mimic the in vivo structure of tumours and tissues [3]. Cells in 2D culture have been found to have altered morphology and cell signalling and gene expression profiles compared to their in vivo counterparts [4]. Furthermore, in drug discovery approaches, lead anti-cancer compounds identified in vitro using 2D methods have been found to lack cancer activity when used in patients with malignancies [5].

Human skin explants, which utilise waste skin from surgical procedures, have been shown to have some advantage over reconstructed skin models because they contain all skin cell types, and the stratum corneum maintains a normal function with comparable physiological permeability [6, 7]. Explants have been developed as genotoxicity testing platforms, which are used to optimize delivery vehicles for mRNA therapeutics, test anti-viral therapies for Human Simplex Virus infection, examine dermatokinetics for topical anti-melanoma therapeutics, develop regenerative burn models, and shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity compared to in vivo human irritant patch testing when evaluating cosmetics [8].

While human explants are increasingly used for translational dermatological research, it is beneficial for the baseline intra-individual and inter-individual variability of immune cells within skin specimens to be assessed. This may have an impact on the design of studies aiming to decipher whether changes in skin immunology should be attributed to background baseline variability or to the effect of a test compound. Specifically, due to the availability and accessibility of abdominoplasty skin as a source of skin for explant studies, determining the variability in the number and location of skin immune cell populations present in abdominoplasty skin has implications for the usefulness of human skin explants in assessing the immune cell impact of therapeutics and toxins.

Methods

Ethical approval

The project titled ‘Development of a Human Skin Model to Assess Topical Pharmaceutical and Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Toxicity and Therapy Effects’ was granted Human Research Ethics Approval by the following committees: Greenslopes Research and Ethics Committee (approval number 17/46), Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 1800000116), and the Office of Research Ethics University of Queensland (approval number 2018000823).

Abdominoplasty specimens

After providing informed consent, abdominal skin specimens were collected from 5 female patients undergoing abdominoplasty procedures at Pindara Private Hospital, Gold Coast, Australia. Three 5-mm biopsies from each were defatted and fixed in 3 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin for 16 h at room temperature. After fixation, samples were transferred to 70% ethanol prior to paraffin embedding.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry staining

Four-micrometre-thick sections were dewaxed and rehydrated using a Leica Autostainer XL (Leica Microsystems Pty Ltd., Mt Waverley, Australia) and incubated in 0.5% H2O2 in Tris-buffered saline for 5 min to quench endogenous peroxidase. Antigen retrieval and antibody stripping was performed using a Biocare Medical DC2002 Decloaking Chamber (Biocare Medical, Pacheco, USA). Primary antibodies (from Dako and Abcam; anti-FoxP3 [clone 22510); anti-CD4 (clone 4B12), anti-CD3 (polyclonal), anti-HLA-DR (clone TAL.1B5), anti-neutrophil elastase (clone EPR7479), anti-CD14 (clone EPR3653), anti-CD1a (clone EP3622), anti-Langerin (clone EPR15863), anti-CD11c (clone EP1347Y), anti-CD69 (clone EPR21814), and anti-CD8 (clone C8/144B)) were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Slides were incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies at room temperature for 15 min, followed by signal amplification by incubating with Opal tyramide reagents (Akoya Biosciences, Marlborough, USA) at room temperature for 10 min. Slides were counterstained with DAPI and mounted with coverslips.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry image acquisition and analysis

Slides were scanned at 20× magnification using a Perkin & Elmer Vectra 3 Spectral Scanner Microscope (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, USA). Image analysis was performed using inForm tissue analysis software (Akoya Biosciences). Images were spectrally unmixed using inForm as the spectral library source. Cell segmentation was performed using DAPI as a nuclear counterstain. Cells were classified for marker co-expression using the Double Positivity (2×2-bin) scoring method on inForm as described elsewhere [9, 10].

Results

To visualise and quantify immune biomarkers in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) abdominoplasty skin sections, we established 4 immunofluorescence biomarker staining panels to allow analysis using multiplex immunohistochemistry. These were as follows: 1) CD3, CD4, and FoxP3 to identify CD3+CD4+ helper T cells and CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells; 2) CD3, CD8, and CD69 to identify CD3+CD8+ cytotoxic CD8 T cells and CD8+CD69+ resident memory CD8 T cells; 3) HLA-DR, CD14, and neutrophil elastase to identify general antigen-presenting cells including macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils, respectively; and 4) CD11c, CD1a, and Langerin to identify dermal dendritic cells and Langerhans cells. Sections were subsequently scanned using the Vectra 3 automated quantitative pathology imaging system and analysed with inForm software. A representative example of staining and automated phenotype and score mapping is presented in Figure 1 A (in each image, epidermis on the left, dermis on the right). Except for Langerin, which was mainly expressed in the epidermis (data not shown), the majority of immune markers were found to be expressed in the dermal layers. Thus, our analysis approach allowed multispectral and automated imaging detection and measurement of weakly expressed and overlapping biomarkers in abdominoplasty skin within a familiar digital pathology workflow.

Figure 1

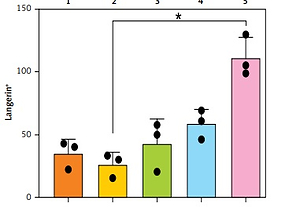

A – Representative automated image analysis of multiparameter immunofluorescence panels for CD3, CD4, and FoxP3 in the skin. Phenotype map: each dot represents the phenotype assigned to a DAPI-positive cell by the custom inForm algorithm. Score map: scoring function classifies cells according to co-expression into 4 classes (double negative, single positive for marker 1 or 2, and double positive). Red – single positive CD3; Green – single positive FoxP3; Yellow – single positive CD4; Pink – double positive; Blue – double negative. B – Enumeration of immune populations across 5 patient samples as determined by inForm analysis. Each dot within a graph represents a separate biopsy. Bars represent mean + SD from 3 biopsies per patient, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, *p < 0.05. Y-axis – numbers of cells, X-axis – patient number

As shown in Figure 1 B, the inForm software was able to successfully quantitate numbers of immune cells in 5-mm abdominoplasty biopsies, even when less than 50 cells per section were present. The fold difference in average immune cell subset numbers between patients was 7.8 for CD3+CD4+ helper T cells, 5.2 for CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells, 5.8 for CD3+CD8+ cytotoxic CD8 T cells, 6.1 for CD8+CD69+ resident memory CD8 T cells, 19.0 for HLA-DR+ antigen presenting cells, 4.7 for CD14+ monocytes, 4.0 for neutrophil elastase+ neutrophils, 6.3 for CD11c+ dermal dendritic cells, 2.5 for CD1a+ dermal dendritic cells, and 4.2 for Langerin+ Langerhans cells (Table I). Intra-patient variability was relatively conserved for some subsets across patients, e.g. 1- to 1.9-fold for CD14+ monocytes, 3.6- to 4.7-fold for CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells, and 1.3- to 2.9-fold for Langerin+ Langerhans cells; however, it differed more markedly for other subsets, e.g. CD11c+ dermal dendritic cell counts varied 1.6 fold for patients 1 and 4, but 5.6 fold for patient 5.

Table I

Inter- and intra-patient variability in immune cell counts

Discussion

Abdominoplasty skin explants are increasingly used to make translational dermatological research discoveries in a broad range of disciplines including skin healing [11], compound testing [12], and the role of immune cells in disease [13, 14]. However, there is growing evidence to suggest that the skin at different anatomical sites differs in multiple immunological contexts, including in immune cell prevalence, cytokine and chemokine production, and the production of anti-microbial peptides [15]. Furthermore, it has been reported that white adipose tissue associated with abdominoplasty skin from obese individuals contains unique subsets of innate lymphoid cells and distinct subsets of dendritic cells and macrophages not found in abdominoplasty skin from lean individuals [16]. Hence, both the site of skin harvest and the abdominoplasty donor themselves may have significant impacts upon the prevalence of immune cells within abdominoplasty skin explants.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry is a relatively new platform that has been reported to enable quantitative and qualitative assessment of immune cells, including Th17 cells, in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded melanoma tissue [17, 18]. Using this approach, we established 4 staining panels that permitted the detection markers associated with helper T cells, regulatory T cells, cytotoxic CD8 T cells, resident memory CD8 T cells, HLA-DR+ antigen-presenting cells, monocytes, neutrophils, CD11c+ and CD1a+ dermal dendritic cells, and Langerhans cells in abdominoplasty skin explants. Our data indicate that there is considerable variation in immune cell numbers between patients and between biopsies from similar healthy skin regions of the same patient. The impact of this variation on the usefulness of abdominoplasty skin explants for research will depend on the experimental purpose and design. For example, a large influx of immune cells might be expected to enter immune-mediated diseased and/or inflamed skin [19, 20], in which case the 2- to 7-fold differences in immune cell numbers we detected in otherwise healthy skin may have less of an impact if being used for comparative controls. However, the levels of immune cell variation would certainly be impactful if, for example, the focus was on biology connected to a specific subset, such as HLA-DR+ cells, which varied 19-fold between patients. Although small scale, this study provides useful baseline data detailing the abundance and variance of immune cell subsets in abdominoplasty skin explants.