Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the world, with more than 17.9 million persons affected per year. It accounts for approximately 30% of all deaths, out of which 80% occur in low- to middle-income countries [1–6]. It is estimated that by 2020, about 23.6 million people will die from CVD, alarmingly maintaining the first rank in mortality worldwide [4, 5]. CVD encompasses a group of disorders that affect the heart and blood vessels, including ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease (PAD), heart failure, and sudden death, among other atherothrombotic and non-atherothrombotic diseases. It is estimated that 92.1 million adults in the United States have at least one type of CVD. Among these patients, 46.7 million are people aged > 60 years [3, 4,6].

In Mexico, CVD represents one of the most significant causes of disability and premature death, leading to a considerable increase in the cost of health care [5–7]. In 2008, CVD mortality accounted for more than 17% of all deaths in the country, and in 2012 approximately 109,000 people died from heart disease [7, 8]. Currently, CVD is the leading cause of death in the Mexican population. However, a small but constant decrease has been recently observed due to the implementation of programs such as the Infarction Code [6, 8]. Along with diabetes mellitus, the National Health System considers CVD as the main non-communicable health problem in the country [4]. We aimed to analyze the population mortality due to specific CVD causes of death during the period 2011–2015. Our hypothesis was that CVD mortality in Mexico is beginning to reach a plateau in annual population-adjusted mortality rates. These results are part of a comprehensive analysis that includes recent periods and non-communicable causes of death within the country.

Material and methods

In this descriptive observational study, a total database of 3,105,975 death certificates provided by SINAIS/DGIS was consulted during the period from January 2011 to December 2015. This database is made of all death certificates issued during the 2011–2015 period in the whole country (a total of 32 federal states) [9]. Briefly, in Mexico death certificates are registered locally in the informatics department of each healthcare institution, public ministry, and other legal entities of the respective municipality. These death records are consolidated by the SINAIS/DGIS in a comprehensive electronic database by using the global WHO format. A database is freely available for each year with the basic cause of death, excluding contributing causes and comorbidities [9]. Records of diseases associated to death due to atherothrombotic CVD were identified (as defined by the American Heart Association [AHA]), with the codes of the International Classification of Diseases tenth revision (ICD-10). We selected and analyzed ICD-10 classification codes of ischemic heart disease (I25.0, I25.1, I25.2, I25.3, I25.4, I25.5, I25.6, I25.8, I25.9), heart failure (I50.0, I50.1, I50.9), cerebrovascular disease (I60.0, I60.1, I60.2, I60.3, I60.4, I60.5, I60.6, I60.7, I60.8, I60.9, I61.0, I61.1, I61.2, I61.3, I61.4, I61.5, I61.6, I61.8, I61.9, I63.0, I63.1, I63.2, I63.3, I63.4, I63.5, I63.6, I63.8, I63.9, I65.0, I65.1, I65.2, I65.3, I65.8, I65.9, I66.0, I66.1, I66.2, I66.3, I66.4, I66.8, I66.9, I67.0, I69.0, I69.1), and peripheral artery disease (I73.1, I73.9, I74.0, I74.1, I74.2, I74.3, I744, I74.5, I748, I74.9). These ICD 10 codes were used to put together a separate database to analyze established atherothrombotic CVD, excluding hypertension, heart arrhythmias, and thrombotic venous diseases. In this new electronic database, we identified the proportion of deaths associated with the specific causes of atherothrombotic CVD that were selected for the present analysis, taking into account the corresponding ICD-10 codes. Then, a database of death certificates was extracted (i.e., 132,148 deaths from atherothrombotic CVD as a basic cause of death), taking into account the basic causes of death reported by the Mexican Ministry of Health during the aforementioned period. These databases were analyzed without patient identification, social security numbers, hospital record numbers, or any personal contact details. A consent disclaimer was obtained for the present analysis of public raw data [9]. No risk exposures were derived from the present retrospective official database analysis.

Mortality rates were assessed by using the frequencies of ICD-10 usage (indicating that an individual died from CVD) and computed per 100,000 inhabitants of Mexico according to the population size of each year reported by the National Census of Population and Housing [10]. Age-standardized mortality rates were calculated using the World Health Organization (WHO) population model. For this calculation, the following data were used: Mexican national population at mid-year in the period of the prefixed analysis (2011–2015) and the number of deaths recorded in death certificates within each year of the period, for the selected specific causes of death and for CVD as the sum of the specific cases (ICD-10 codes). Demographic data are presented as relative frequencies. The Pearson χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate) was used to compare the frequencies of qualitative nominal variables between two groups. All p-values for comparisons were two-tailed and results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Economically active age groups were analyzed according to the definitions of the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics (INEGI) for this population sector [10].

Results

A total of 3,105,975 death certificates issued in Mexico were identified for the study period from January 2011 to December 2015. After applying the selection criteria for individual certificate records, a unified database was obtained with a total of 594,370 records corresponding to CVD as the basic cause of death. During 2011, a total of 107,227 death certificates accounted for CVD, which rose to 130,279 death certificates in 2015 (53.2% deaths corresponded to men in 2015) (Table I). The age-standardized mortality rate for CVD as the basic cause of death exhibited a trend that steadily increased during the period, from 92.7 per 100,000 in 2011, to 107.7 per 100,000 in 2015 (Table II).

Table I

Cardiovascular disease analyzed through death certificates during the period 2011–2015, according to sex. The numbers in parentheses represent the proportion that each year accounts for over the 5-year period

Table II

Number of deaths and age-standardized mortality rates per specific cardiovascular disease, 2011–2015

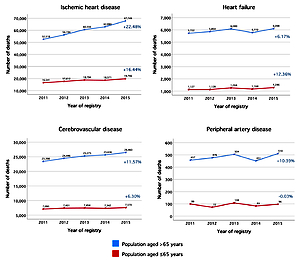

The survival age was significantly shorter (p < 0.001) in men (mean age at death: 72.04 ±16.23 years) than in women (mean age at death: 77.73 ±14.77 years) (Figure 1 A). Such gender-related discrepancies in the age at death according to sex were maintained for ischemic heart disease (71.97 ±15.88 vs. 78.65 ±14.02 years, p < 0.001), heart failure (75.69 ±17.84 vs. 78.80 ±16.05 years, p < 0.001), cerebrovascular disease (71.71 ±16.72 vs. 75.55 ±15.71 years, p < 0.001), and peripheral artery disease (75.02 ±16.59 vs. 79.83 ±14.68 years, p < 0.001). In general, ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease had the shortest survival compared to heart failure or peripheral artery disease (Figure 1 B).

Figure 1

A – Kaplan-Meier plot showing the survival curves according to sex in the overall atherothrombotic cardiovascular disease death certificates database, 2011–2015. B – Kaplan-Meier plot showing survival curves according to specific causes of atherothrombotic cardiovascular diseases analyzed in this study, 2011–2015

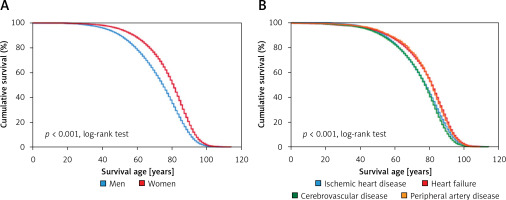

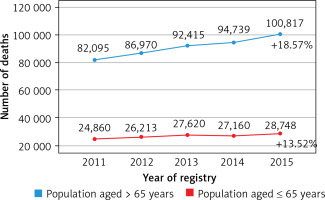

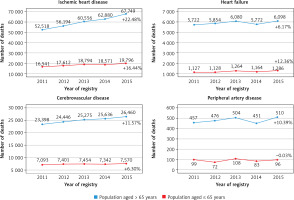

The crude number of deaths increased steadily among the population aged > 65 years, with a slope that was disproportional to the population growth in that particular age group (Figure 2). The increase was steeper for ischemic heart disease in the older population, while it was essentially stable for heart failure or peripheral artery disease (Figure 3).

Figure 2

Crude number of deaths due to total atherothrombotic cardiovascular disease, according to age and year of record. Numbers followed by “+” or “–” express the percentage increase or decrease, respectively, between the first and last year analyzed

Figure 3

Crude number of deaths due to specific causes of atherothrombotic cardiovascular disease, according to age and year of registry. Numbers followed by “+” or “–” express the percentage increase or decrease, respectively, between the first and last year analyzed

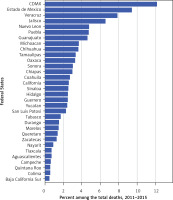

The Mexican federal states contributed differently to CVD mortality during the period (Figure 4), without differences according to year of registry, age or sex.

Discussion

In this study we observed that CVD mortality shows a growing pattern, essentially at the expense of ischemic heart disease. Compared to women, men showed a younger age at death (i.e., survival age), which is an epidemiological concept that differs from “life expectancy,” which is a statistical measure of the mean time a human is expected to live, based on the year of birth. Moreover, cause-specific analysis showed that the shortest survival was observed for ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, which are the causes of CVD death with the highest death tolls. These findings are relevant in general terms, since it has been estimated that approximately 80% of deaths due to CVD occur in low- to middle-income countries, affecting both sexes equally [1–6]. Moreover, the global CVD burden has increased over recent decades, in high- and low-to-middle-income nations. In Mexico, these diseases still represent a serious public health problem that entails a significant burden in terms of prevalence and medical care costs [1, 5, 6, 8–12].

Compared to previous reports about the speed of growth of atherothrombotic mortality in Mexico [13], in the present analysis, we have potentially observed the historical inflection point of a progressive slowing of CVD mortality growth in Mexico. This phenomenon can be explained by a more widespread awareness among the Mexican population about the risk factors and clinical features of diseases that occur as a consequence of artery occlusions, as well as the implementation of programs such as the Infarction Code to control atherothrombotic diseases through the development of high-impact strategies aimed at raising awareness of the main causes of CVD morbidity and mortality [6, 8]. Nonetheless, in order to determine that such epidemiological pattern change is sustained, an extended analysis on recent years should be performed, and it is currently in preparation.

The economically active population is made up of people who provide labor for the production of goods and services. Among the most important causes of death within this sector of the population are diabetes mellitus and CVD, especially in people aged 45 to 64 years [9]. In the present study we observed that CVD deaths occurred in high numbers among the economically active population, an alarming finding considering the loss of the productive force of the nation. Furthermore, CVD mortality is higher in the most important federal states of Mexico, ranked by gross domestic product (GDP) and population size, such as Mexico City (a new federal state in Mexico), Jalisco, the State of Mexico, Veracruz, Puebla, and Nuevo León [10–12]. The explanation for this phenomenon could be related to the exposure to risk factors prevailing in large urban areas, although with the current methodology we cannot discard underdiagnosis of CVD entities in the small or underdeveloped regions of Mexico. This study presents key hypotheses currently being tested by our group and by other researchers.

Mexico is an upper middle-income country that has one of the highest prevalence rates for diabetes mellitus in the world [10, 13], in addition to the fact that glycemic control in people with this disease is often deficient and relates to frequent concomitant pathologies (e.g., CVD, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and end-stage renal impairment, among several others) that increase morbidity and mortality [14–16]. The WHO has suggested that there may be problems in reporting mortality associated with diabetes mellitus as the basic cause of death, because diabetes mellitus can in turn lead to CVD and other chronic micro- and macrovascular complications; therefore, when mutually exclusive basic causes of death are considered, CVD-related death in patients with diabetes mellitus may be assigned to the latter instead of atherothrombotic CVD [14, 17–21].

Our results are comparable to those recently observed in the Brazilian population [22], specifically with respect to the overall trends of CVD deaths. A remarkable difference versus the Brazilian report is that we limited the analysis of ICD-10 classification codes to specific atherothrombotic diagnoses, excluding the unspecific codes related to “diseases of the circulatory system” (ICD-10 codes I00–I99) and other unspecific codes to avoid the inclusion of garbage codes. This methodology, of course, might underestimate the CVD burden in Mexico, which will feature in a future analysis by our research team. Moreover, there is high potential for misclassification of the basic cause of death biased towards general diagnoses such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension, which represent very common comorbid conditions. This paper draws attention to what is considered a basic cause of death and how the mortality analyses are performed. Future studies need to address this issue. This fact can also be deduced from a comparison with CVD mortality in Argentina [23], which, globally, is higher than that reported in the present analysis [24]. Nevertheless, our study aimed to analyze the population mortality of specific atherothrombotic diseases, which may be important when discussing specific etiologies that conform the cardiovascular burden of disease.

The present study has limitations that must be addressed for an accurate interpretation of data. It is worth noting that this analysis addresses a relatively short period of time and that the last year is 2015; therefore, recent changes in epidemiological patterns cannot be detected. Another topic of discussion is that only the basic cause of death in the certificates was studied, as this is the only cause of death available in the public SINAIS/DGIS databases. Consequently, it is not known how many cases of people who died from CVD were related to other diagnoses, such as diabetes mellitus. It is also possible that heart failure has been either underdiagnosed or misclassified with other related causes of death, such as diabetes or hypertension [25]. Moreover, since a death certificate usually does not give an account of any previous atherothrombotic events, we were not able to analyze the possible influence of recurrent (versus first-ever) events explaining the differences in the causes of death analyzed. Another limitation is the lack of data on comorbidities and risk factors that may indirectly contribute to CVD deaths. Nevertheless, the results from this study are based on official death certificates pertaining to the Mexican public health system, which is the source of information for other estimations about disease burden [26].

In conclusion, although CVD mortality in Mexico is still increasing (particularly associated with ischemic heart disease among the population aged > 65 years), compared with other reports we have observed a progressive slowing of CVD mortality growth. Moreover, compared to other clinical forms of CVD, patients with ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease have the shortest survival. Male sex is also associated with a reduced survival age. These findings establish a basis for new research hypotheses aimed at better explaining the sex and regional disparities observed in our emerging economy.