Introduction

Arterial ischaemic stroke (AIS) comprises a set of rapidly developing clinical symptoms characterized by a sudden, focal or generalized brain disorder resulting from the dysfunction of brain circulation, lasting 24 h or longer or leading to death. The frequency of ischaemic stroke in children is relatively low in contrast to adults. Recent data demonstrated that in developed countries the prevalence of both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke ranges from 3 to 25 cases per 100,000 children, while in newborns this frequency is higher, i.e. 1 in 4000 live births [1]. A study from Taiwan reported that the 2-year prevalence for ischaemic lesions in children was 5.2 per 100,000 per year [2]. Recent data from Germany showed an overall incidence of 0.41 per 100,000 per year [3]. In Switzerland, the incidence of posterior AIS in children was established at 0.183 per 100,000 (i.e. 16% of all childhood AIS) [4].

AIS causes deleterious neurological consequences that affect the daily functioning of the patient as well as the costs of medical care and rehabilitation both in adults and in children. The most frequent consequences of AIS in children are motor disorders, mainly hemiparesis, epileptic seizures, aphasia, or intellectual delay [5–7]. If AIS occurs in the perinatal period, it may have an impact on cognitive and behavioural deficiencies appearing in the patient’s future life [8]. In addition, paediatric patients are at a high risk of recurrent stroke and post-stroke mortality [5, 9]. In the USA, cerebrovascular disease was found among 10 of the most common causes of death in the paediatric population [10].

Valuable sources of strategic information in regard to arterial ischaemic stroke in adults world-wide are the databases managed by public health institutions [11–13]. In contrast, analysis of data on AIS in the paediatric population coming from national registries are scarce [2].

Registry-based data show many advantages, i.e. they are already collected, and the researchers do not need to organize and finance data collection from individual patients or search medical records in their hospitals. In addition, they can serve as a sampling frame or a reference for researchers who would like to select a sample or evaluate the representativeness of their own sample. According to the definition of the Statistical Office of the European Union EUROSTAT, these data are of good quality, which is understood broadly as relevance, accuracy, timeliness and punctuality, accessibility and clarity, coherence, and comparability [14]. The definitions of variables and domains are already fixed, unambiguous, and comprehensive. There are no sampling errors or missing data; data are available immediately after inclusion, including long comparable time series, comparability over time and between domains, and coherence with other health statistics.

In Poland, the National Health Fund (NHF) registry is the only public payer for healthcare services that covers the whole country, i.e. 16 administrative regions. The NHF has the right to process the personal data of the patients, with an emphasis on monitoring their health as well as their needs for health services, drugs, and medical devices [15]. As for now, no special database concerning paediatric AIS has been established in Poland; thus, the Polish NHF is considered as a reliable source of epidemiological data from all over the country. Consequently, such data may enable real-time monitoring of the health status of patients: co-morbidity, disease burden, as well as therapeutic patterns. Analyses based on such comprehensive data will help define health priorities and specially help in appropriate assignation of public funds. Full-scale data on paediatric AIS may provide an alternative novel insight into the epidemiological status of AIS in children.

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of childhood AIS, as well as the parameters related to AIS hospitalisation, including age, gender, region, month and season of the year at admission, duration, and costs, based on data from the NHF registry within the period 2011 to 2020.

Material and methods

Study population

For this retrospective study, we included individual, anonymous data from the NHF concerning the hospitalisation of children with AIS registered in Poland in the period 2011–2020. Data were obtained based on formal approval from the NHF to implement the “Maps of Health Needs” project.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: hospitalisation due to ICD-10 I63.0–I63.9. We also comprised patients hospitalized due to I64, which included arterial ischaemic, haemorrhagic, and other strokes; age from 0 to 18 years. This inclusion was done after the discussion with a clinically experienced paediatric neurologist.

In the analysed group of children with AIS hospitalised in Poland during the period 2011–2020, 5 subgroups according to age were recognised: a) neonates or infants (from birth to the end of the 12th month of life), b) toddlers and pre-school children (from the 1st year of life to the end of the 6th year of life), c) pre-pubertal children (7th to 10th year of life), d) early pubertal patients (11th to 14th year of life), and e) adolescents (aged 15–18 years).

The patients’ consent as well as the formal approval of the Local Ethics Committee were not required because database analysis is not treated in Poland as medical experimentation according to Polish law (Act of 5 December 1996 on professions of physicians and dentist (Journal of Laws of 2021, item 790 as amended). The present study was retrospective and non-invasive because we did not have direct contact with the patients during the research and the data obtained from the NHF were anonymous.

Hospitalisation-related parameters

For each hospitalisation, the following data were available from the NHF database: regional branch of the NHF in which the patient was hospitalised, regional branch of the NHF in which the patient was registered, age, gender, group of diseases according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) classification, date and type of admission, date and type of discharge, and total cost of the procedure provided rated by the NHF (amount in Polish zloty). Hospitalisation costs were expressed in EUR and USD during the analysis according to the exchange rate as of 31 December 2020. Based on the registry data, we calculated the following: duration of hospitalisation, month and season of the year at admission, and hospitalisation outside the region of residence.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using Statistica 13 software (STATSOFT, Tulsa, OK, USA) and R language (version R-3.6.2).

The mean and standard deviation values were estimated for numerical variables, and absolute numbers (n) and percentages (%) of the occurrence of items were estimated for categorical variables.

The following statistical tests were used:

Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables between ICD-10 procedures or year of hospitalisation;

F test of variance to compare age, duration, or costs of hospitalisation between ICD-10 procedures or year of hospitalisation;

Pearson’s correlation coefficient to find correlations between age, duration, and costs of hospitalisation.

In analyses of dependent variables against ICD-10 procedures, I63.1 was omitted because it was registered only for 1 patient. The significance level was 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Results

Diagnosis of AIS in paediatric patients

A total of 622 hospitalisations due to paediatric AIS were registered in Poland in the period 2011–2020 (Table I). In all analysed years, stroke not specified as haemorrhage or infarction was the most frequent (31.67%), followed by cerebral infarction, unspecified (18.33%), cerebral infarction due to unspecified occlusion or stenosis of cerebral arteries (15.27%), and other cerebral infarction (14.79%). Furthermore, the ICD-10 procedure of hospitalisations due to AIS did not significantly differ in the analysed period (p = 0.410).

Table I

Paediatric hospitalisations due to arterial ischaemic stroke according to ICD-10 in Poland in the period 2011–2020, n (%)

Gender, age, and season of the year and month at admission to hospitals due to paediatric AIS

AIS occurred more often in boys (367, 59.00%) than girls (255, 41.00%). However, the gender of patients hospitalised due to AIS (p = 0.116) and the ICD-10 procedure (p = 0.891) did not differ significantly in the analysed period.

The mean age of AIS children hospitalised between 2011 and 2020 in Poland was 10.2 ±6.0 years. The age of patients hospitalised due to AIS (p = 0.454) and the ICD-10 procedure (p = 0.201) did not differ significantly in the analysed period.

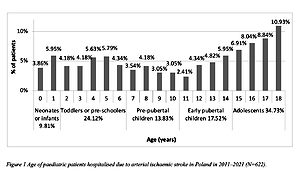

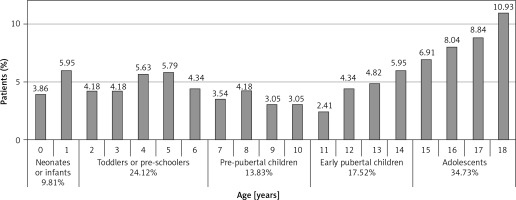

The age distribution in the whole group is shown in Figure 1. The most common age subgroups were adolescents (34.73%), followed by toddlers or pre-school children (24.12%), while the least common was the group of neonates or infants (9.81%).

Figure 1

Age of paediatric patients hospitalised due to arterial ischaemic stroke in Poland in the period 2011–2021 (N = 622)

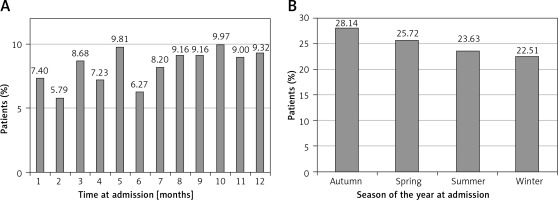

Patients suffered from the disease more commonly in autumn than in other seasons of the year, while October was the dominant month for the illness (Figure 2). However, the month and season of the year at admission and the ICD-10 procedure did not differ significantly in the analysed years (month at admission versus year of hospitalisation p = 0.641, season of the year at admission versus year of hospitalisation p = 0.536, month at admission versus ICD-10 procedure p = 0.935, season of the year at admission versus ICD-10 procedure p = 0.935).

Region of residence of paediatric patients hospitalised due to AIS

A significant difference was found between the region of residence of paediatric patients with AIS and the year of hospitalisation (Table II). In the analysis of total years, the highest percentage of paediatric hospitalisations due to AIS took places in Mazowieckie (11.58%), Śląskie (9.97%), Dolnośląskie (9.65%), Wielkopolskie (9.49), and Małopolskie (9.16%), whereas the number of hospitalisations due to paediatric AIS was lowest in Opolskie (2.73%), Lubuskie (3.38%), Lubelskie (3.54%), and Zachodniopomorskie (3.54%).

Table II

Region of residence of paediatric patients hospitalised due to arterial ischaemic stroke in Poland in the period 2011–2020, n (%)

A total of 57 cases out of 622, i.e. 9.16%, were hospitalised outside the region of residence. Hospitalisation outside the region of residence did not differ significantly in the analysed years (p = 0.286).

Types of admission and discharge, and duration and costs of hospitalisation due to paediatric AIS

The most common type of admission was emergency admission – other cases, while the least common was transfer from another hospital (59.81% and 5.31, respectively) (Table III).

Table III

Admission procedure of paediatric patients hospitalised due to AIS in Poland in the period 2011–2020, n (%)

Regarding discharge type, the most common was a referral for further outpatient treatment (47.43%), while the least common discharge was a referral for further treatment in a medical facility other than a hospital, providing medical services such as inpatient and round-the-clock health services (0.80%) (Table IV).

Table IV

Discharge procedure of paediatric patients hospitalised due to AIS in Poland in the period 2011–2020, n (%)

The duration and costs of hospitalisation did not differ significantly in the analysed years (p = 0.495 and p = 0.495, respectively). Therefore, we analysed the duration and costs of hospitalisation in the entire period together (Table V). ICD-10 procedures significantly differentiated the duration and costs of hospitalisation (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). The most extended hospitalisations were observed for I63.0 and I63.5 procedures. The highest costs of hospitalisations concerned the I63.1 procedure; however, only 1 child was treated within this procedure, which included thrombectomy. Next, high costs were linked with the I63.4 procedure, while the lowest applied to the I64 procedure.

Table V

Duration and costs of hospitalisation due to paediatric AIS according to ICD-10 in Poland in the period 2011–2020

| ICD-10 | Diagnosis | Duration of hospitalisation [days] M ± SD | Costs of hospitalisation, M ± SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLN | EUR* | USD* | |||

| Total | 12.9 ±12.1 | 3,288 ±3,324 | 729 ±737 | 891 ±901 | |

| I63.0 | Cerebral infarction due to thrombosis of precerebral arteries | 17.3 ±8.7 | 3,291 ±1,290 | 730 ±286 | 892 ±350 |

| I63.1 | Cerebral infarction due to embolism of precerebral arteries | 9.0 ±0.0 | 1,2,584 ±0.0 | 2,790 ±0 | 3,410 ±0 |

| I63.2 | Cerebral infarction due to unspecified occlusion or stenosis of precerebral arteries | 15.2 ±12.7 | 4,331 ±2783 | 960 ±617 | 1,174 ±754 |

| I63.3 | Cerebral infarction due to thrombosis of cerebral arteries | 15.1 ±12.4 | 4,108 ±3225 | 911 ±715 | 1,113 ±874 |

| I63.4 | Cerebral infarction due to embolism of cerebral arteries | 15.7 ±17.1 | 5,935 ±11,415 | 1,316 ±2531 | 1,608 ±3093 |

| I63.5 | Cerebral infarction due to unspecified occlusion or stenosis of cerebral arteries | 16.9 ±11.6 | 3,753 ±2330 | 832 ±517 | 1,017 ±631 |

| I63.6 | Cerebral infarction due to cerebral venous thrombosis, non-pyogenic | 16.3 ±12.1 | 4,041 ±2856 | 896 ±633 | 1,095 ±774 |

| I63.8 | Other cerebral infarction | 15.4 ±12.7 | 4,182 ±2636 | 927 ±584 | 1,133 ±714 |

| I63.9 | Cerebral infarction, unspecified | 12.5 ±12.3 | 3,559 ±2862 | 789 ±635 | 964 ±776 |

| I64 | Stroke, not specified as haemorrhage or infarction** | 8.4 ±9.9 | 1,778 ±1327 | 394 ±294 | 482 ±360 |

The duration and costs of hospitalisation were positively correlated to each other (r = 0.525, p < 0.001). The longer the hospitalisation, the higher the average costs of hospitalisation. Age correlated negatively with duration of hospitalisation (r = –0.154, p < 0.001), whereas there was a positive correlation between age and costs of hospitalisation (r = 0.133, p = 0.008). The older the patient, the shorter the average duration of the hospitalisation.

Discussion

In the present study, adolescents aged 15–18 years were the most numerous group of patients. The disease occurred less commonly in neonates or infants (from birth to the first year of life), i.e. in 10%. The frequency of adolescents is in accordance with previously published data on children with AIS diagnosed in Katowice (Southern Poland) [16]. In turn, such a low number of neonates or infants in the present study contradicts the previous data [17]; however, it may result from the fact that AIS in newborns could be classified as other brain diseases using different coding, especially in neonatal departments, because in these cases AIS results from a specific cause and may be scrambled. In the present registry analysis, 4 patients (i.e. 0.64%) were treated with thrombolysis. They were adolescents aged 17–18 years. An earlier study on American children demonstrated a similar frequency (1.6%) of patients receiving thrombolytic therapy. The patients were only males, with a mean age of 11.1 years [18]. Systematic intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy are suggested as potentially effective treatment options in children and adolescents in addition to antiplatelet medication and heparinisation [19].

In the present study, we demonstrated that the experience of thrombolytic therapy in children is very modest, as it was only recently possible to use intravenous thrombolysis in patients aged 16 years and older, and earlier this treatment was only approved in patients over 18 years of age. Because the drug is approved for children > 16 years of age, spreading the benefits and risks will not overstate the cost of hospitalisation. In the adult population, in which stroke is a widespread problem, IV thrombolysis has been the standard treatment for the acute phase of stroke for several years. Given the frequency of stroke in children over 16 years of age, the time needed to gain experience and describe the groups of children treated with thrombolysis will probably be greater.

In the whole group, boys with stroke were more common than girls (59% vs. 41%, respectively). Most researchers also describe a higher incidence of stroke in boys, which relates to both paediatric stroke (risk 1.25) and perinatal stroke (risk 2.0), and this difference remains despite the elimination of trauma as the cause of stroke [20, 21]. An earlier study based on Polish children demonstrated that boys were more prevalent in all age subgroups of analysed patients with AIS (i.e. infants–toddlers, children, and adolescents). Boys significantly outnumbered girls in the POCI and TACI stroke subgroups, while girls predominated in the LACI stroke subgroup [16]. In a group of 1979 children with stroke, both ischaemic and haemorrhagic (aged < 10 years and from 10 to 19 years), analysed in a study from Taiwan, based on the National Health Insurance database, 60.2% were boys [22]. An extremely high percentage of boys with AIS (71%) was observed in a recent Chinese study [23]. Similarly, in Danish research, 67% of children with AIS and varicella infection less than 12 months before the onset of symptoms were boys [24]. The reason why boys suffer from AIS more often is not clear. This may be due to the higher incidence of infections and head injuries in boys compared to girls, or simply because of the greater number of boys in the general population [25].

Stroke in Polish children occurred most frequently in autumn. This may be due to the higher incidence of infections in this season of the year. The available data demonstrated that infections increased the risk of paediatric stroke [26]. In the Canadian study by Carey et al. [27], infection was found to be a risk factor for stroke in every fifth child with posterior AIS. The authors observed, among others, pharyngitis, meningitis, otitis media, or history of chicken pox in the last 12 months prior to stroke. In turn, in children with AIS from Senegal, 3 patients had meningitis, which was assigned to Cryptococcus neoformans (1 case) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (2 cases), which then revealed a stroke [28]. The general effects of infection lead to temporary thrombophilia, and hypercoagulable states are considered a risk factor for AIS in younger patients [29]. Prothrombotic abnormalities also play a critical role in the aetiology of paediatric AIS [30]. In the study by Cao et al. [23], over 73% of analysed stroke children aged 1 month to 4 years had respiratory tract infection with fever, and 33% had thrombophilia.

In patients from Katowice (Poland), AIS appeared most commonly in winter, with significant differences between types of AIS and seasons of the year during which the AIS occurred, i.e. TACI stroke occurred most frequently in the summer, LACI – during winter or spring, and PACI – winter or autumn [31].

The mean length of hospital stay for children with AIS was 12.9 days. Similarly, Cao et al. [23] reported that children with AIS were hospitalised for 5–20 days, with 13 days on average. Regarding the length of stay of children in hospital, usually more than 5 days is the time necessary for all laboratory tests to be carried out to analyse the cause of the stroke. The length and costs of hospitalisation did not differ significantly in the analysed years. This information can be used by the Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System that prepares and verifies health technology assessments, with particular emphasis on technologies that are financed from public funds; it also prepares recommendations for the Minister of Health regarding medical technologies (drug and non-drug) in Poland. Information on the length of stay can affect the revision of the cost of treatment by the above agency and the change in NHF tariffs.

Many factors influence the hospitalisation costs of adult patients, including stroke type and severity, and the length of hospital stay [32]. In the present registry-based analysis, the duration and costs of hospitalisation due to paediatric stroke did not differ significantly in the analysed years. The ICD-10 procedures affected the duration and costs of hospitalisation. The most expensive procedure according to ICD-10 was I63.1; however, it was applied in the case of only one child. The least expensive procedure was I64. The mean cost of paediatric stroke in Poland in 2011–2020 was USD 891. Perkins et al. [32] reported the mean cost of ischaemic stroke of USD 20,927. The duration of hospitalisation correlated positively with costs of hospitalisation (r = 0.525, p < 0.001). The type of ICD-10 procedure affected the length of hospitalisation and its costs significantly. The most expensive procedures were related to cerebral infarction due to embolism of precerebral arteries (I63.1), cerebral infarction due to embolism of cerebral arteries (I63.4), cerebral infarction due to unspecified occlusion or stenosis of precerebral arteries (I63.2), and other cerebral infarction (I63.8) procedures, while the lowest costs applied to cerebral infarction due to thrombosis of precerebral arteries (I64) and stroke, not specified as haemorrhage or infarction (I63.0) procedures.

Previously, data from a Taiwan registry [22] demonstrated that the hospitalisation care costs for stroke are higher in children than in adults because the proportion of haemorrhagic cases is greater in paediatric populations. The authors reported that the mean inpatient costs, including both first and subsequent hospitalisations, were higher for patients < 10 years old and those aged 10–19 years (USD 3565 per case) than for adult patients with stroke (USD 1933) [22]. In addition, the costs were found to be higher for the recurrent cases. Chen et al. [22] demonstrated also that costs of hospitalisation due to ischaemic stroke were comparable for children < 10 years old and those between 10 and 19 years of age (approximately USD 2400). In our analysis, mean costs of AIS hospitalisation were significantly lower and ranged from USD 482 to USD 3410 depending on the ICD-10 procedure, with a mean of USD 891 per case.

The present study has some limitations. First, the number of cases is relatively low. In a Taiwan study concerning a comparable period, almost 2000 children with AIS were identified [22]. Therefore, we can infer that AIS is a rare disease in Poland. Second, the low number of children with AIS in smaller (population wise) regions (Lubelskie, Lubuskie, Opolskie, Warmińsko-Mazurskie, and Zachodniopomorskie) is alarming. This might indicate the weaknesses of the health service and failure to detect the disease, especially in the Opolskie and Lubuskie regions. Third, NHF data include only hospitalisations financed by public funds. In Poland, hospitalisation costs are covered by public funds; however, they may also be paid directly by patients. Therefore, AIS in children is unlikely to be treated privately. In addition, the study has a retrospective character, which may result in limited access to some specific patient information. Last, the cost analysis concerns only single hospitalisations due to AIS. The costs do not include treatment of the consequences of AIS, i.e. subsequent hospitalisations and rehabilitation.

Our study is the first analysis of paediatric patients with AIS based on the NHF registry in Poland, which covers the entire population. This allowed for inclusion of a sizeable group of patients hospitalised in all regions of Poland due to AIS, in contrast to the clinical studies most often coming from one medical centre and performed on small groups.

In conclusion, in the present study, the occurrence of AIS varies between regions of Poland. AIS is more common in boys than in girls and more often found in adolescents (15–18 years) than in younger children. Every 10th hospitalisation due to AIS is away from the patient’s place of residence. The most common type of admission was emergency admission while in case of discharge type, the most common was a referral for further outpatient treatment. The mean hospital stay due to paediatric AIS is about 2 weeks, with an average cost of hospitalisation of approximately USD 900.

It is therefore worth using health registries for population analyses of various diseases and population distributions of demographic and hospitalisation-related characteristics.