Introduction

In developed countries, as many as half of all available hospital beds can be occupied by patients 65 years or older [1]. Even medically successful interventions leave many community-dwelling elderly survivors, who often have low social adaptability and are thus at an elevated risk of death [2], dependent on informal caregivers who are only rarely prepared and supported enough to efficiently bear their burden [3]. This in turn translates into inadequate care, leading to imbalanced diets and nutritional deficiencies [4], generally poor compliance among old age patients (over 60% have poor medication adherence and management), and unsatisfactory treatment results, despite the use of expensive multidrug therapies [5]. The progressing aging of modern societies is also reported to rapidly increase the general healthcare burden, due to the rapid growth in demand for inpatient services, driven by longer lifespans and multiple comorbidities [6] coexisting with the limited availability of medical staff and care workers, which can only be lessened in part by the application of modern medical technologies, including telemedicine in the case of chronic diseases [7]. The situation is often further exacerbated by poor management of medical services, resulting in longer than objectively necessary lengths of stay, readmissions, avoidable hospitalizations, low-quality medical services, and low levels of patient satisfaction. Elderly patients are typically characterized by the longest average length of stay (LOS) [6], which can only to a limited extent be attributed to modifiable hospital organization-related issues [8]; sometimes this can be associated with hospital-independent factors, including high levels of stress among informal caregivers or difficulties in transferring a dependent old patient to a nursing home [9]. The LOS in the case of older patients can be accurately predicted at admission using evaluation tools such as the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI), a derivate of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) [10].

Comorbidities are very common in older adults [11], and they are a significant cause of increasing utilization of both healthcare and social care resources in aging societies [12]. Conditions involving chronic pain are in particular much more common and involve on average more sites in the elderly than in younger people; they thus frequently increase healthcare use [13]. At the same time, paradoxically, the healthcare system in Poland is still not suited to efficiently manage pain in older patients [14], even though proper permissive medical guidelines for the use of analgesics exist [15]. Old age is an independent perioperative factor in death risk in the case of some surgical procedures [16], and prolonged hospitalization may have additional detrimental health effects, increasing mortality and shortening survival time, as does any additional factor which strips an ill elderly person of his or her sense of control over life [17]. Hospitalized older adults are also likely to develop hospital-acquired complications, such as pressure injuries, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or delirium, which not only significantly increase LOS but also worsen basic treatment outcomes; the risk of such complications increases significantly when any comorbidities exist, as is quite common among the elderly [1]. As many as 40% of elderly patients develop functional decline following hospitalization [18], preventing their prompt discharge home [19], and this can even progress after discharge [20]. Consequently, early interventions aimed at managing nosocomial infections and preventing physical deconditioning, in association with planning discharge as soon as possible and in advance, can limit LOS in the elderly [21].

It has been demonstrated that each comorbidity in a hospitalized older patient (especially dementia), each hospital-acquired complication (including those most common in the elderly, such as pressure injuries, pneumonia, urinary tract infections and delirium), elevated health status at admission, and even each year of age above 50 predict significant excess hospitalization costs [11]. Unfortunately, for many years in Poland, financial assets have been assigned to medical services providers merely on the basis of crude and arbitrary estimates of local populations’ health needs, not taking into account the specific requirements of many groups of patients, including the elderly [22]. Notoriously, there have been frequent reports of system-based significant underpayments (sometimes as high as 40–46% of the actual costs incurred by the medical service providers) on the part of the main state-run health insurance fund (Narodowy Fundusz Zdrowia – NFZ) in the case of services affecting elderly patients and others, such as palliative care [23, 24]; however, specialized units dealing with the specific needs of elderly patients, such as geriatric and palliative care units, tend to be more cost effective than regular hospital wards, which mostly provide acute medical care [25] and are unable to provide all the full-length rehabilitation and prophylactic exercise programs that can be highly beneficial for elderly patients [26]. Introducing exercise programs for chosen groups of hospitalized older patients, especially those who require assistance or supervision on admission, can improve the health outcomes and discharge functional ability while at the same time lowering the total treatment costs by shortening the LOS and limiting complications, although the responses of individual patients may vary considerably on a case-to-case basis [27]. The best effects can be expected when the exercise program is started as early as possible, optimally within the first 2 days of the elderly person’s hospital stay [28].

It is difficult both to assess the total cost of hospital treatment of a single patient and to make comparisons between different patient groups, as there are both direct and indirect costs to be taken into account, and methods of analysis can vary [29]. However, there are some hospitalization parameters that can be calculated or directly associated with costs, and can therefore can be taken as the basis for direct comparisons; these include: LOS, total direct cost of hospitalization per patient, and per patient cost of laboratory tests and radiologic diagnostic procedures.

Material and methods

Data on 312,250 patients admitted to University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland in the years 2012–2015 were retrieved from the hospital electronic health record system, anonymized, aggregated, and analyzed in order to determine the treatment costs of elderly patients in comparison to those in other age groups. The analysis considered two main age groups, younger than 65 years and 65 years and older, and also took account of the following subgroups: 65–74 years (the “young old”), 75–84 years (the “old old”) and 85 years and older (the “oldest old”). Statistical quantitative analysis was carried out using StatSoft Statistica 10.0 PL. For the analyzed variables, descriptive statistics and distributions were calculated using the cardinality and contingency tables with the Maximum-Likelihood Chi-square test (M-L Chi-square); the level of statistical significance was taken to be p < 0.05. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University, Poland (decision number: KB.-608/2017).

Results

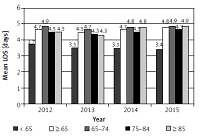

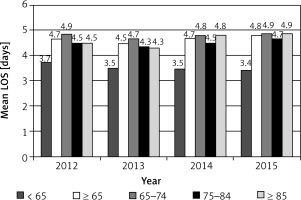

Analysis of the mean LOS of patients treated at University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland in the years 2012–2015 demonstrated significant differences in the values calculated for patients aged below 65 years and those 65 years old and older (3.5 and 4.7 person-days, respectively). The mean LOS for the elderly patient subgroups was 4.8 person-days in the case of the 65–74-year-old group, 4.5 person-days for those 75–84 years of age, and 4.6 person-days for those 85 years and older.

The differences in LOS between the below-65 and the 65-and-older groups increased significantly over the four years from 1.0 person-day in 2012 to 1.4 person-days in 2015. These differences were observed in all the subgroups, but the increase over the four years was greatest for the 85-years-and-older subgroup (from 0.8 to 1.5 person-days) and for the 65–74-year-old group (from 1.2 to 1.5 person-days), as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Mean length of stay of patients of University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland, 2012–2015, for the under-65 age group and the 65+ age group, and by age subgroups: 65–74 years, 75–84 years, and 85 years and older (in person-days). Data source: information system of University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland

The differences in the LOS between the age group subgroups were significant in the vast majority of hospital wards, as shown in Figure 2. The patients aged 65 years and older had the longest LOS in the following units: Neurology Ward; Orthopedics and Motor Organ Traumatology Ward; Neurosurgery Ward; and Internal Diseases, Professional Diseases and Hypertension Ward. The longest LOS was found predominantly in the 85 years and older subgroup. Only in the case of less used units, including the Emergency and Admissions Ward, Ophthalmology Ward, and Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Ward, were the mean LOS values lower for elderly patients than in the below-65 age group.

Figure 2

Mean length of stay of patients at wards of University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland, 2012–2015, for the under-65 age group and the 65+ age group, and by age subgroups: 65–74 years, 75–84 years, and 85 years and older (in person–days). Data source: information system of University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland

Analysis of the mean total direct cost of hospitalization of patients in University Clinical Hospital, Wrocław, Poland in the years 2012–2015 revealed a significant difference: in the case of the below-65-years-old group, the cost was PLN 4,907.12 (around EUR 1,154.62), while in the case of the 65-years-and-older age group, it was PLN 6,357.15 (EUR 1,495.80).

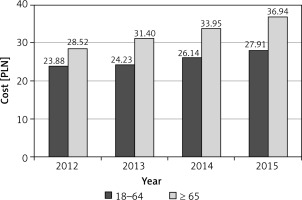

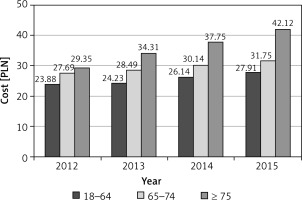

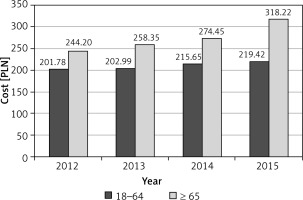

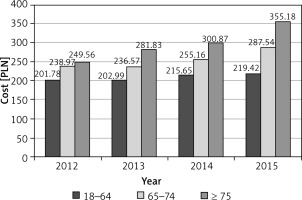

The mean costs of laboratory tests in patients belonging to the different age groups were calculated; not only were they significantly higher every year in the 65+ age group, but the difference between the age groups increased rapidly with each passing year, from 21% in 2012 to 45% in 2015, as demonstrated in Figure 3. Moreover, the older the age subgroup was, the more rapid was the observed increase in the mean laboratory test costs per patient (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Mean per patient cost of laboratory tests at University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland, 2012–2015, for the under-65 age group and the 65+ age group (in PLN). Data source: information system of University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland

Figure 4

Mean per patient cost of laboratory tests at University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland, 2012–2015, for the under-65 age group, the 65–74 age group, and the 75+ age group (in PLN). Data source: information system of University Clinical Hospital, Wroclaw, Poland

The mean costs of radiological diagnostic procedures in patients belonging to different age groups were calculated: as with the laboratory tests, they were not only significantly higher each year in the 65+ age group, but the difference between the age groups also increased rapidly with each passing year, from 19% in 2012 to 32% in 2015 (Figure 5). Moreover, the older the age subgroup was, the more rapid was the increase in the mean per patient laboratory test costs (Figure 6).

Discussion

There are no previous Polish publications with which to directly compare the current study data. This study has confirmed the previously reported significant differences in direct cost-generating hospitalization parameters (particularly the LOS) between patient age groups, as well as a trend of rapid increases over time, especially in the oldest age subgroup (85 years and older), and especially in hospital units dealing with age-related cardiovascular and neurological disorders or with conditions resulting from them, including fall-related bone fractures. The exceptional findings regarding the Ophthalmology Ward can be explained by the large amount of 1-day surgical procedures in patients with cataracts. In the case of the other exceptions, the Emergency and Admissions Wards, the LOS are by definition short and comparable across all age subgroups, though they are slightly shorter in the case of elderly patients, probably because less hesitation exists than in case of younger patients about whether they need to stay in hospital, as in the vast majority of cases, elderly patients do require hospital treatment. The shorter LOS for elderly patients in the Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Ward holds true only for the 65–84 age subgroup, as these patients often undergo planned surgical interventions with a comparably good prognosis when they are in generally good health, while younger patients more often need urgent operations (especially for trauma), and patients aged 85 years and older are often in poor general health.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated higher mean hospitalization costs of patients aged 65 years and older in Poland in comparison to younger groups. This can be explained not only by the longer mean LOS, but also by the more complex and expensive medical treatment, including laboratory and radiologic diagnostics, which continue to increase in the oldest age groups. The differences in hospitalization costs across patient ages are rapidly increasing over time, and thus demand urgent systemic solutions, including adequately increased financing of elderly patients’ hospital treatment.