Introduction

Aldosterone, the final component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, plays an essential role in regulation of blood pressure by maintaining electrolyte and water homeostasis [1, 2]. The classical role of aldosterone occurs via a genomic mechanism [3]. The aldosterone-mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) complex will bind to its hormone-responsive elements within the nucleus and promotes the expression of target genes [3]. At present, several examinations on aldosterone have turned to nongenomic actions which present a rapid onset (≤ 30 min) [4–7].

A previous in vitro study has revealed the nongenomic action of aldosterone in enhancing the formation of angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) dimerization [8]. AT1R dimerization is essential for functional consequences of G-protein activation of various physiologic conditions [9, 10]. Moreover, increased AT1R dimerization plays a contributory role in pathologic conditions including hypertension and atherosclerosis [11]. In cultured mouse mesenteric arterioles, aldosterone nongenomically stimulates the activity of intracellular transglutaminase 2 (TG2), resulting in enhanced AT1R dimerization [8]. TG2 is a catalytic enzyme which catalyzes post-translational modification of proteins by covalent bond formation between free amine groups [12]. Besides TG2, elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been shown to enhance AT1R dimerization in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells [13]. In cultured porcine proximal tubular cells, aldosterone nongenomically activates NADPH oxidase by translocating p47phox from the cytosolic compartment to bind its membranous subunit at the plasma membrane and then generates ROS production [14]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that ROS rapidly stimulates TG2 activity in cultured Swiss 3T3 fibroblast cells [15]. Taken together, it appears that MR, TG2, NADPH oxidase, p47phox, and ROS might play important roles in the nongenomic action of aldosterone on AT1R dimerization. Despite the above in vitro evidence, there are no available in vivo data. Moreover, no in vitro data are available regarding the nongenomic action of aldosterone on angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT2R) dimerization.

To obtain in vivo data, the present study was conducted in the rat kidneys 30 min following treatment with normal saline solution, or aldosterone; or receiving pretreatment with eplerenone (MR blocker) or with apocynin (NADPH oxidase inhibitor) 30 min before aldosterone injection. Western blot analysis was performed to measure protein abundances of dimeric and monomeric forms of AT1R and AT2R as well as TG2 and p47phox. Immunohistochemistry was performed for localization of TG2 and p47phox proteins.

Material and methods

Experimental design

Male Wistar rats weighing 200–240 g (National Laboratory Animal Center, Mahidol University, Nakornpathom, Thailand) were given conventional housing and diet. All animal protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Research, Chulalongkorn University (Permit number IRB 7/57). Serum creatinine of each rat should be < 1 mg/dl [16, 17]. The rats were divided into four groups (n = 8/group): sham (normal saline solution; NSS: 0.5 ml/kg BW by intraperitoneal injection, i.p.); Aldo (aldosterone 150 μg/kg BW, diluted in NSS, i.p.; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA); or pretreatment with eplerenone (MR blocker; 15 mg/kg BW; diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide, i.p.; Sigma; Ep. + Aldo) or with apocynin (NADPH oxidase inhibitor; 5 mg/kg, diluted in NSS, i.p.; Sigma; Apo. + Aldo) 30 min before aldosterone injection [16–19]. We used this aldosterone dose as previously performed in the studies of nongenomic action of aldosterone on the protein expression of upstream/downstream mediators [6, 16, 17]. Therefore, in the present investigation, we further examined the effect of this dose on protein expression of ATR dimerization, TG2, and p47phox.

On the date of the experiment, 30 min following injection of NSS or aldosterone, the rats were anesthetized with thiopental (100 mg/kg BW, i.p.). Kidneys were removed, and a half of each kidney was fixed in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at –80°C until use for measurement of dimeric and monomeric forms of ATRs (AT1R and AT2R), TG2, and p47phox protein abundances by Western blot analysis. The other half of renal tissue was fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde for localization of TG2 and p47phox proteins by immunohistochemistry [6, 16, 17].

Western blot analysis

The renal tissue samples were homogenized on ice with a homogenizer (T25 Basic, IKA, Selangor, Malaysia) in homogenizing buffer ((20 mM Tris-HCl; pH 7.5, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 M sucrose, and 5% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)). To get rid of crude debris, the kidney homogenates were centrifuged at 4,000 g (Sorvall Legend X1R, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) for 20 min at 4°C. To harvest plasma membrane, the supernatant was further centrifuged at 17,000 g for 20 min at 4°C [20]. The pellet was dissolved in buffer. Total protein concentration was measured with Bradford protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The measurement of protein abundance was performed as previously described [6, 16, 17]. Proteins were resolved on 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for AT1R, AT2R (dimeric and monomeric forms), TG2, p47phox, β-actin, and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were incubated with primary monoclonal antibody to AT1R (1E10-1A9: sc-81671; 1 : 200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), AT2R (C-18: sc-7420; 1 : 300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TG2 (TG100: MA5-12915; 1 : 1,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), p47phox (D-10: sc-17845; 1 : 250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or to β-actin (C4: sc-47778; 1 : 2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by the respective horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Immunoreactive proteins were detected by chemiluminescence detection (SuperSignal West Pico kit; Pierce) and documented by using a Molecular imager ChemiDoc XRS system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Relative protein levels of AT1R and AT2R (dimeric and monomeric forms), TG2, and p47phox in each sample were presented as a percentage of the control normalized to its β-actin content.

Immunohistochemical study

Detection of protein localization was performed as previously described [6, 16, 17]. Paraffin-embedded kidney sections were cut into 4 μm thick slices. The slides were deparaffinized and endogenous peroxidase was blocked by treatment with 3% H2O2. The sections were incubated with the primary antibody TG2 (1 : 20,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), or p47phox (1 : 150; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4°C overnight, followed by the respective horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Bio-Rad Laboratories), then reacted with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine solution (Sigma). Three pathologists independently scored the staining intensity on a semi-quantitative five-tiered grading scale from 0 to 4 (0 = negative; 1 = trace; 2 = weak; 3 = moderate; 4 = strong) as previously described [6, 16, 17].

Statistical analysis

Results of renal AT1R and AT2R (dimeric and monomeric forms), TG2, and p47phox protein abundances were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical differences between the groups were assessed by ANOVA (analysis of variance) with post-hoc comparison by Tukey’s test where appropriate. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical tests were analyzed using the SPSS program version 22.0 (IBM Corp. Chicago, IL, USA). The median staining intensity (score) of renal TG2 and p47phox protein expression was presented as previously described [6, 16, 17].

Results

Aldosterone enhances renal ATRs dimer protein abundances

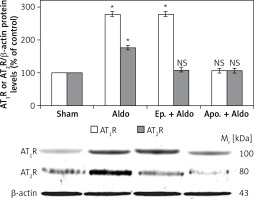

The protein levels of AT1R and AT2R were assessed by Western blot analysis (Figure 1). Aldosterone enhanced protein abundances of dimeric forms of AT1R (100 kDa) and AT2R (80 kDa) from sham (100%) to be 278 ±7% and 175 ±9%, respectively (p < 0.001). Apocynin could block aldosterone-induced dimeric protein abundances of both AT1R (105 ±4%, p = 0.12) and AT2R (103 ±5%, p = 0.57). Eplerenone had an inhibitory effect only on dimeric forms of AT2R protein (108 ±6%, p = 0.23). The dimeric protein levels of AT1R were still enhanced to be 276 ±8% (p < 0.001) in the presence of MR blocker. Aldosterone did not alter protein levels of monomeric forms of AT1R (50 kDa) or AT2R (41 kDa) (data not shown).

Figure 1

Western blot analysis of renal dimeric forms of AT1R and AT2R protein abundances in sham, Aldo, Ep. + Aldo, and Apo. + Aldo groups. Histogram bars show the densitometric analyses ratios of AT1R, or AT2R to β-actin intensity, and the representative immunoblot photographs are presented

Data are means ± SD of 8 independent experiments. *P < 0.001 compared with the respective sham group.

Aldosterone stimulates renal transglutaminase 2 (TG2) and p47phox protein abundances

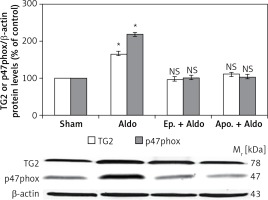

The protein levels of TG2 (78 kDa) and p47phox (47 kDa) in the rat kidney were measured by Western blot analysis (Figure 2). Aldosterone significantly elevated protein abundances of TG2 and p47phox from sham (100%) to be 165 ±8% and 218 ±11%, respectively (p < 0.001). Both eplerenone and apocynin, when each was used, completely abolished the effect of aldosterone-induced TG2 (97 ±5%, p = 0.48; 110 ±10%, p = 0.40) and p47phox (101 ±5%, p = 0.90; 104 ±4%, p = 0.40), respectively.

Figure 2

Western blot analysis of renal TG2 and p47phox protein abundances in sham, Aldo, Ep. + Aldo, and Apo. + Aldo groups. Histogram bars show the densitometric analyses ratios of TG2, or p47phox to β-actin intensity, and the representative immunoblot photographs are presented

Data are means ± SD of 8 independent experiments. *P < 0.001 compared with the respective sham group.

Renal TG2 protein expression is activated by aldosterone

Protein expression of TG2 in the cortex of sham is shown in Figure 3 A and Table I. The expression was grade 1 (trace) in the glomerulus, whereas the intensity was grade 4 (strong) in the peritubular capillary (Pcap). The immunostaining was moderately diffuse in the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT). No staining was noted in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) or cortical collecting duct (CCD). Aldosterone did not alter the intensity score in these areas (Figure 3 B). Interestingly, aldosterone induced the translocation of TG2 protein expression from the cytosol to the luminal membrane of PCTs. Eplerenone or apocynin pretreatment could blunt the effect induced by aldosterone (Figures 3 C, D). The staining in the PCT returned to the same pattern as the sham.

Table I

Median staining intensity (score) of renal TG2 and p47phox protein expressions

[i] Staining intensity: 0 = negative, no reactivity; 1 = trace, faint or pale brown staining with less membrane reactivity; 2 = weak, light brown staining with incomplete membrane reactivity; 3 = moderate, shaded of brown staining of intermediate darkness with usually almost complete membrane reactivity; 4 = strong, dark brown to black staining with usually complete membrane pattern, producing a thick outline of the cell [6, 16, 17]. PCT – proximal convoluted tubule, DCT – distal convoluted tubule, CCD – cortical collecting duct, Pcap – peritubular capillary, TALH – thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop, MCD – medullary collecting duct, VR – vasa recta, tLH – thin limb of Henle’s loop.

Figure 3

Representative immunohistochemical staining micrographs of renal TG2 protein expression in the cortex (A–D), the outer medulla (E–H), and the inner medulla (I–L) from sham (A, E, I), Aldo (B, F, J), Ep. + Aldo (C, G, K), and Apo. + Aldo (D, H, L). Original magnification 400× (A–D) and 200× (E–L)

In the outer medulla, aldosterone elevated the intensity score in all studied areas (Figure 3 F). Eplerenone or apocynin could lessen the immunoreactivity induced by aldosterone in the thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop (TALH), vasa recta (VR) and thin limb of Henle’s loop (tLH) (Figures 3 G, H). The expression in the medullary collecting duct (MCD) remained. In the inner medulla, aldosterone enhanced the immunoreactivity in all studied regions (Figure 3 J). Both eplerenone and apocynin, when each was used, could inhibit the effect of aldosterone on TG2 expression (Figures 3 K, L; Table I).

Renal p47phox protein expression is induced by aldosterone

As shown in Figure 4 and Table I, the immunostaining of p47phox protein was obvious at the basolateral membrane of the renal tubules in both the cortex and the medulla. Furthermore, the expression was also well noted in the renal vasculature. In the cortex (Figure 4 B), aldosterone markedly enhanced the expression to be strong in the glomerulus, PCT, DCT and Pcap while the intensity in the CCD was grade 3 (moderate). Pretreatment with apocynin showed a greater inhibitory effect than eplerenone on aldosterone-induced p47phox expression (Figures 4 D, C respectively).

Figure 4

Representative immunohistochemical staining micrographs of renal p47phox protein expression in the cortex (A–D), the outer medulla (E–H), and the inner medulla (I–L) from sham (A, E, I), Aldo (B, F, J), Ep. + Aldo (C, G, K), and Apo. + Aldo (D, H, L). Original magnification 400× (A–D) and 200× (E–L)

In the outer medulla, aldosterone elevated the intensity score in TALH and tLH (Figure 4 F). Eplerenone or apocynin could decrease the immunoreactivity in both areas (Figures 4 G, H). The expression in the MCD and VR remained. In the inner medulla, aldosterone enhanced the immunoreactivity in all studied regions (Figure 4 J). Eplerenone pretreatment had a greater blocking effect than apocynin (Figures 4 K, L; Table I).

Discussion

To our knowledge, these are the first in vivo data simultaneously demonstrating that the renal protein abundances of dimeric forms of AT1R and AT2R are enhanced 30 min following aldosterone administration (Figure 1). AT1R dimerization is important for functional consequences of G-protein activation [9]. Previous studies regarding AT1R found that AT1R dimerization influences receptor activation mechanisms including agonist/antagonist affinity, efficacy, trafficking, and specificity of signal transduction mediators [9, 10]. Under physiologic conditions, AT1R dimerization promoted sodium reabsorption in microdissected rat proximal tubule by stimulating Na+-ATPase activity [10]. In pathologic conditions, an increased AT1R dimerization was reported in monocytes isolated from hypertensive patients [11]. Moreover, monocytes of ApoE knockout mice exhibit high AT1R dimer levels which cause atherosclerosis [11]. Indeed, elevation of AT2R dimerization was found in the renal cortex from a preeclampsia rat model [21].

In the present study, aldosterone enhanced AT1R dimers but did not alter AT1R monomers. A previous study in vascular smooth muscle cells also showed that aldosterone increases AT1R dimers while the monomers are unchanged [8]. No data of AT2R dimerization related to aldosterone were reported in that study. The mechanism of this phenomenon remains to be established. ATRs belong to the seven membrane classes of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) which can dimerize in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [22]. A recent study in HEK cells demonstrated that corticotropic-releasing factor receptor type 1, a member of GPCRs, is assembled as dimers in the ER and transported to the plasma membrane [23]. Therefore, it is likely that aldosterone might enhance both AT1R and AT2R dimerizations within the ER and these dimers are transported to the plasma membrane, resulting in unchanged monomers.

This study is the first to demonstrate that aldosterone-induced AT1R dimerization occurs via an MR-independent pathway while aldosterone-induced AT2R dimerization is dependent on the MR pathway (Figure 1). Regardless of the MR pathway dependence or not, the enhancements of AT1R and AT2R dimerizations were suppressed by apocynin (Figure 1), indicating the mechanistic role of NADPH oxidase in stimulating dimerization of both ATRs.

As stated earlier, previous in vitro studies in various tissues suggested that there might be an interrelationship among NADPH oxidase, p47phox, ROS, and TG2 in contributing to the nongenomic stimulating action of aldosterone on AT1R dimerization. In support of this contention, the present study illustrates that aldosterone rapidly stimulates TG2 and p47phox, both of which are inhibited by apocynin (Figure 2). Therefore, in the MR-independent pathway, aldosterone might activate ROS via NADPH oxidase and then stimulate both TG2 and AT1R dimerization in the kidney.

Regarding the mechanism of AT2R dimerization, in the present study, aldosterone elevated TG2 protein abundance via MR (Figure 2). A previous study reported that TG2 mediates cross-linking of AT2R into oligomers in HEK cells [24]. However, TG2-induced AT2R dimerization has not been shown in any studies. It is likely that aldosterone activates TG2 and then stimulates AT2R dimerization. One attractive effect of aldosterone on AT2R dimerization is enhancing ROS, since translocation of p47phox into the plasma membrane represents activation of NADPH oxidase and then leads to generation of ROS [25, 26]. The present study is the first to demonstrate that the nongenomic action of aldosterone on AT2R dimerization elevates plasma membrane protein abundance of p47phox by an MR-dependent mechanism (Figure 2). A former study reported that aldosterone nongenomically reduces cytosolic p47phox but the effect of plasma membrane p47phox on AT2R dimerization was not examined [14]. Our data showed that aldosterone-induced AT2R dimerization is abolished by apocynin (Figure 1). The results suggest that aldosterone-induced ROS production from activation of NADPH oxidase has a potential role in AT2R dimerization.

Immunohistochemistry studies revealed that TG2 in the sham group showed weak and diffuse immunostaining in glomeruli and tubules (Figures 3 A, E, I). Previous studies in normal rat kidney also revealed the similar baseline regional distribution of TG2 protein as in the present investigation [27, 28]. In the present study, aldosterone stimulated the expression of TG2 mostly in the medulla area (Figures 3 F, J). Although the expression levels were not altered in the cortex, aldosterone nongenomically translocated the TG2 protein from the cytosol to the luminal membrane while eplerenone or apocynin could normalize the immunoreactivity (Figures 3 A–D). A previous study demonstrated that both AT1R and AT2R are highly abundant in the luminal membrane of renal tubular cells, for example in the proximal tubules and medullary TALH [29, 30]. As such, aldosterone-induced TG2 might play a significant role in dimerization of AT1R or AT2R to regulate ion transport in the renal tubules. Moreover, the prominent TG2 expression was present in Pcap and VR by aldosterone (Table I). This implies some important effects of TG2 on these renal vascular functions. Of note, enhanced TG2 expression in the kidney has been related to the development of kidney diseases. TG2 protein abundance, activity, and expression were enhanced in the puromycin aminonucleoside-injection-induced experimental rat model of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, subtotal nephrectomy-induced renal fibrosis, IgA nephropathy, and the rat renal transplantation model of chronic allograft nephropathy [27, 28, 31, 32]. Furthermore, TG inhibition could ameliorate experimental diabetic nephropathy, reduce fibrosis and preserve function in experimental chronic kidney disease [33–36].

For p47phox protein localization, immunostaining in the sham group was present in the glomeruli and renal vasculature in both the cortex and the medulla (Figures 4 A, E, I). This baseline regional distribution of p47phox protein is similar to previous studies in normal rat kidney [37–39]. Of interest, the present study shows more obvious staining at the basolateral membrane of renal tubules than those previously reported [37–39]. This discrepancy may be due to the more specific (monoclonal) p47phox antibody used in the present study. Aldosterone enhanced p47phox protein expression at the basolateral membrane in both the cortex and the medulla and this enhancement was normalized by eplerenone or apocynin (Figure 4). Interestingly, induction of renal p47phox protein expression has been implicated in some renal diseases such as diabetic nephropathy and nephrolithiasis [37, 38]. Deletion of p47phox could attenuate the progression of kidney fibrosis and reduce albuminuria in diabetic nephropathy and nondiabetes-mediated glomerular injury [40, 41].

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first in vivo study demonstrating that aldosterone nongenomically increases renal TG2 and p47phox protein expression and then activates AT1R and AT2R dimerizations. Aldosterone-stimulated AT1R and AT2R dimerizations are mediated through activation of NADPH oxidase. Aldosterone-induced AT1R dimer formation is an MR-independent pathway, whereas the formation of AT2R dimer is modulated in an MR-dependent manner.