Introduction

In Egypt, cerebellar ataxia (CA) is prevalent with 27.16 per 100,000 people diagnosed yearly [1]. New neuroprotective strategies are sought to slow down the progression of the disease by targeting the molecular process involved in its pathogenesis. Such strategies include regenerative treatment involving the use of growth factors or stem cells [2, 3]. The most commonly used type of stem cells is mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) because they have unique properties of self-renewal, differentiation capacity, and paracrine actions [4]. Bone marrow (BM) is an available source of MSCs [5], but adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) are considered the best alternative source due to the reported lower incidence of rejections, tumourigenesis, or ethical problems [6, 7]. Studies have shown conflicting results regarding the superiority of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) over ASCs [8, 9]. In view of the inconsistent findings in the literature regarding the best source of cells, this study aimed to compare the potential therapeutic role of BM-MSCs vs. ASCs in a CA rodent model.

Material and methods

Animals

All experimental protocols were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University. All efforts were made to minimise animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. Forty female adult Wistar albino rats weighing 120–150 g were procured from the animal centre at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Suez Canal University. Rats were allowed to acclimatise for 15 days prior to the experiment. Rats were maintained with food and water ad libitum in an inverted dark-light cycle. They were divided randomly into 4 groups (control, model monosodium glutamate (MSG) group, BM-MSC group, and ASC group). An additional 6 adult male albino rats weighting 250–300 g were used for isolation of retroperitoneal adipose tissue and BM from the femur and tibia [10].

Isolation and characterisation of mesenchymal stem cells

Rats (n = 6) were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the tibia and femur were dissected. Medullary cavities of the bone were flushed with 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for collection of marrow cells. The cells were centrifuged at 200 g for 10 min and the supernatant removed by aspiration. The cells were re-suspended in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 15% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 50 U/ml gentamicin and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. Adherent cells were harvested when 50–60% confluence was reached with 0.25% trypsin [11]. For ASC isolation, the fat tissue in the perirenal region was minced and digested for 40 min at 37°C using collagenase type I. The action of collagenase was neutralised by adding DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS. The digested tissue was filtered using a 100 µm filter mesh (Sigma-Aldrich) and centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min and subjected to erythrocyte lysis. Cells were cultured in 37°C, 5% CO2 in complete culture media. When the adherent cells reached confluence, they were detached with 0.25% trypsin and re-suspended in supplemented media [12].

Morphological and immunophenotypic characterisation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and adipose tissue stem cells

The adherent cells had fibroblastic morphology (spindled cells with elongated nuclei). For the flow cytometry analysis, cells were incubated in a blocking solution (PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 1% FBS) for 10 min. After centrifugation, cells were re-suspended in the blocking solution and stained with the following antibodies for 30 min: APC anti-CD45 mAb, PE anti-CD29 mAb, and FITC anti-CD90 mAb. Cells were acquired on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, USA) following standard procedures and analysed using Cell Quest Pro Software (Becton Dickinson, USA).

Induction of cerebellar ataxia and stem cell therapy

Monosodium glutamate was purchased from NATCO (laboratory chemical reagent powder – prepared by dilution with saline, ratio 1 : 1). Due to literature controversy regarding optimal MSG dose and effects, we first conducted a pilot study (n = 6) to assess the most effective dose with the least extra-cerebellar manifestations (e.g. oculomotor disturbances) and mortality [13]. Animals were trained on the rotarod apparatus daily and received intraperitoneal (IP) injection of either 3.5, 4, or 6 gm/kg body weight of MSG once daily for 6 days. On day 6, rats were assessed on the rotarod. On day 7, rats were sacrificed for histopathological assessment of the cerebellum which showed marked degeneration of the Purkinje cell layer, confirming the development of CA. This pilot showed that MSG at a dose of 4 gm/kg was optimal to induce CA with zero mortality.

After acclimatisation, animals were randomly divided into 4 groups: control, MSG, BM-MSC, and ASC (n = 10 each). The control group received 1 ml saline IP once daily for 6 days, whereas the last 3 groups received 4 gm/kg of MSG IP once daily for 6 days to induce CA [14]. On day 7, once CA was established, animals were randomised to receive 1 ml PBS, or 1 × 106 BM-MSCs, or 1 × 106 ASCs (suspended in 250 µl PBS) IV via the tail vein, as previously described [15]. Animals underwent physiological assessment of motor functions 1 week after MSC or saline treatment followed by serial assessments over the subsequent 4 weeks. Animals were then sacrificed, and their cerebellum processed for histopathological and immunological assessments, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Physiological assessment of motor functions

Rotarod test

In order to assess balance and motor coordination, each rat was placed on a rotating rod (10 cm long and 4 cm in diameter) and the speed was set at 18 rpm. The rotating cylinder was mounted 40 cm above the base of the bench. The elapsed time from putting the animal on the shaft of the rotarod to it falling to the ground (latency) was recorded. All rats were pre-trained for 3 consecutive days before starting the experiment, to ensure they were able to remain on the rotating rod for at least 1 min [16]. The cut-off time was predetermined as 180 s.

Open-field test

The apparatus comprised an open-field arena (113 × 113 × 44 cm) made of white painted plywood with a floor painted with black lines forming a 5 × 5 cm pattern. Rats were introduced individually in the open field arena and behavioural parameters were videotaped for subsequent analysis for 5-minute sessions. Rats were observed for ambulation (the number of squares crossed), number of stops, number of rearing occurrences, mobility duration, and locomotor activity (number of squares divided by the total number of stops) [17].

Quantitative gait analysis

The apparatus had an open field (60 × 60 × 40 cm) illuminated by a light, in which a runway (4.5 cm wide, 42 cm long, borders 12 cm high) was arranged to lead out into a dark wooden box (20 × 17 × 10 cm). The forelimbs and hind limbs of each rat were dipped in red and blue non-toxic colours, respectively, to record the footprints. Rats were allowed to walk across a white sheet toward a custom-built dark escape box, leaving a trace of their paw prints on the sheet. Six middle steps of a series of steps were analysed for forelimb stride length, hind-limb stride length (HSL), and stance width [18].

Histological assessment of cerebellar architecture

Haematoxylin and eosin staining

A pathologist (blinded to all groups) counted and averaged the Purkinje cells in 10 fields as a measurement of linear density of Purkinje cells. For each rat, the number of Purkinje cells (identified by cell body) was determined for each section using light microscopy at 400× magnification. Counts were reported as the number of Purkinje cells per distance measured (µm). Total Purkinje cell density was expressed as a mean value of the cell number per millimetre length of the cerebellar folia [19].

Cresyl fast violet

Sections were dewaxed by xylene for 30 min and then coated with filtered Cresyl fast violet for 20–30 min to analyse the intensity of staining of Nissl substance in cerebellar neurons and glial cells. Healthy neurons had visible nucleus, nucleolus, and Nissl substance stained blue to violet. A small rim of cytoplasm circling the entire nucleus is a useful feature to distinguish small neurons from astrocytes Optical density was measured using Image Pro Plus software [20].

Immunohistochemical examination of bax and Bcl-2

Cerebellar tissue sections were rinsed three times in xylene. Tissue sections were pre-blocked for 30 to 45 min in TNK solution (100 mmol/l Tris, pH 7.6 to 7.8; 550 mmol/l NaCI; 10 mmol/l KCI) containing 2% (w/v) BSA (ICN Chemicals; San Diego, CA), 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1% normal goat serum. Either pre-immune, polyclonal anti-Bax immune (Gene Tex, 1 : 1000 to 1 : 2000 v/v) or polyclonal anti-Bcl-2 immune (Gene Tex, 1 : 800 to 1 : 1500 v/v) sera were added in the same solution and the slides were left overnight at room temperature. The Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was calculated by using the percentages of stained cells [21].

Immunohistochemical examination of vascular endothelial growth factor

The slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 : 100 dilution of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) primary antibody (Gene Tex). Following a wash with PBS, tissue sections were incubated for 30 min with Vectastain Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vectastain Elite Rabbit IgG Kit PK-6101) and then washed and left for 30 min with Vectastain reagent. Colour development was formed after a few minutes incubation with a solution containing Vector Impact DAB (Vector SK-4105) which were detected under microscope) until staining intensity is optimal. Sections were counterstained with Harris’s haematoxylin for 5 min. Slides were captured with a light microscope (Olympus model BH2) [22].

Assessment of cerebellar insulin-like growth factor-1 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The cerebellum was homogenised in PBS on ice then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant was collected and stored at –80°C. An appropriate amount of PBS was added to the cerebellum before homogenisation based on its weight. Quantitative measurement of cerebellar insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) was done using the RayBio® Rat IGF-1 ELISA kit.

Polymerase chain reaction analysis of male-specific sex-determining region Y gene

Genomic DNA was prepared from cerebellar tissue homogenate of the rats in both stem cell-treated groups using a Blood-Animal-Plant DNA Preparation kit (Jena Bioscience GmbH, Jena, Germany). To provide independent evidence that BM-MSCs or ASCs can home and exist after cerebellar degeneration, a male-specific marker, sex-determining region Y (SRY) gene, was used to identify donor-derived cells in female recipients. DNA from normal female and male rat tissues was used as negative and positive control, respectively. The male-specific marker (SRY gene primer sequences) was used to amplify Y specific regions, and PCR product size (104 pb) was obtained from published sequences [23].

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All values were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean. Differences among mean values were assessed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey post-hoc analysis. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Mesenchymal stem cells improved motor performance

Open field test

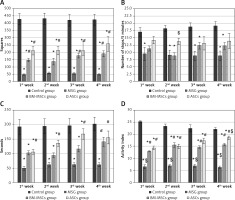

Monosodium glutamate induced poor mobility in the open field test over all sessions of assessment compared to controls in all parameters measured: number of squares crossed (Figure 1 A), number of stops (Figure 1 B), mobility duration (Figure 1 C), and locomotor activity (Figure 1 D). Treatment with either MSCs significantly improved the number of squares crossed and locomotor activity starting at the first week, with ASCs showing superior improvement in locomotor activity at the fourth week over BM-MSCs (p < 0.05 each, Figure 1 A–D). There was no significant improvement in the numbers of stops in response to treatment.

Figure 1

The motor performance of rats in open field tests. Rats were observed for number of squares crossed (A), number of stops (B), mobility duration (C), and locomotor activity (D) in a 5-minute session. The monosodium glutamate (MSG) group showed a decrease motor performance compared to the control group started in the first week. Either type of stem cells improved all these parameters except the number of stops, as compared to the MSG group. Mean ± SEM were analysed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey post-hoc test

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, *significant p-value in comparison to control group, #significant p-value in comparison to MSG group and $significant p-value in comparison to bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells group.

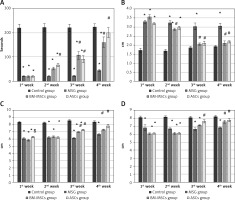

Rotarod test

Monosodium glutamate induced low latencies in all sessions of assessment compared to controls. Adipose tissue stem cells improved latency earlier (on the second week) compared to BM-MSCs (on the third week, Figure 2 A).

Figure 2

The motor performance in rotarod test and quantitative gait analysis. Rats were observed for time spent on a rotating rode (A), stance width (B), fore-limb stride length (FSL) (C), and hind-limb stride length (D). The monosodium glutamate group showed deterioration compared to the control group started at the first week. Adipose tissue stem cells group showed significant improvement in time spent in rotarod test started at the second week and all gait parameters started at the third week. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells group showed significant increase in time spent in rotarod test and FSL started at the third week, stance width in the second week, and hind limb stride length started at the fourth week. Mean ± SEM were analysed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey post-hoc test

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, *significant p-value in comparison to control group, #significant p-value in comparison to monosodium glutamate group and $significant p-value in comparison to bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells group.

Quantitative gait analysis

Monosodium glutamate induced significant reduction in both fore-limb and HSL in addition to wide-based gait compared to controls. Treatment with either MSCs significantly improved gait parameters (Figures 2 B–D).

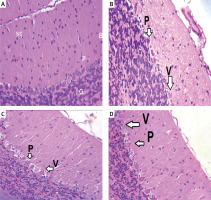

Mesenchymal stem cells restored the Purkinje cell layer

Monosodium glutamate induced marked histopathological changes in the Purkinje cell layer with widely distorted and shrunken Purkinje cells, leaving vacuoles. Treatment with either of the MSCs decreased the number of MSG-induced distorted Purkinje cells with restoration of normal architecture of the cerebellar cortex (Figure 3). Monosodium glutamate also induced a significant decrease in the linear density of Purkinje cells (p = 0.035) in comparison to controls. Treatment with either of the MSCs significantly increased the linear density of Purkinje cells compared to MSG (p = 0.004, Table I).

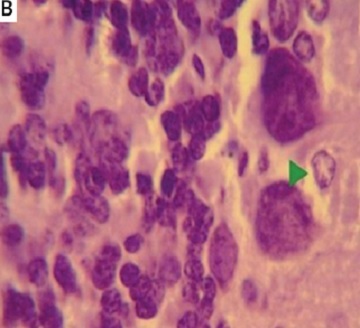

Figure 3

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained cerebellar sections of study groups A–D. A – Control group. B – Monosodium glutamate group. C – Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells group. D – Adipose tissue stem cells group (H&E 400×). Control group showed normal appearance with scattered small stellate (SC) and basket cells (B) in the molecular layer. Crowded small cells with deeply stained nuclei (G) in the granular cell layer and large flask shaped cells, uniformly arranged Purkinje cell layer. Monosodium glutamate group showed widely displaced, distorted, and shrunken Purkinje cells (P), leaving vacuoles (V) in intercellular spaces. Both stem cell groups showed restoration of the normal architecture of the cortex with decreased number of distorted Purkinje cells

Table I

Measurements of linear density of Purkinje neurons

| Variable | Purkinje linear density |

|---|---|

| Control group | 19.667 ±4.4 |

| MSG | 12 ±2.4* |

| MSC group | 14.667 ±8.5*$ |

| ASC group | 17.5 ±10.5*$ |

Using Cresyl violet stain, MSG induced a marked decrease in Nissl’s granules within the perikarya of Purkinje cells, with a mean optic density of 0.223 ±0.003. Treatment with either of the MSCs increased Nissl’s granules within the perikarya of Purkinje cells, with means of 0.35 ±0.002 and 0.51 ±0.001, respectively. Treatment with ASCs resulted in a more significant increase in Nissl granule content compared to BM-MSCs (p-value = 0.001, Figure 4). In the control group, Purkinje cells were with oval rounded basophilic nuclei and a dark basophilic thin rim of cytoplasm concentrated near the plasmalemma, indicating concentrated Nissl granules. Molecular and granular neurons were also darkly stained. In the MSG group, Purkinje cells were with pale diffuse basophilic cytoplasm, indicating dispersion of Nissl granules within the cytoplasm. Both MSC-treated groups showed staining affinity similar to controls, suggesting restoration of Purkinje cells.

Figure 4

Optical density of Cresyl fast violet stain in study groups (A) photomicrographs of sections in the cerebellar cortex of rats (B–E). Control group showed purple Nissl granules (Δ) in the perikarya of Purkinje cells (B). The monosodium glutamate (MSG) group showed decreased purple Nissl granules (C). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BM-MSCs) group (D) and adipose tissue stem cell group (E) showed increased purple Nissl’s granules. Mean ± SEM were analysed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey post-hoc test

*Significant p-value compared to control group, #significant p-value compared to MSG group and $significant p-value compared to BM-MSC group.

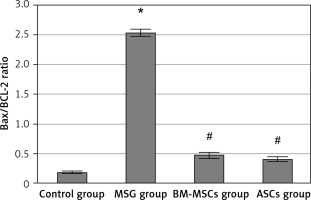

Mesenchymal stem cells improved the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio

For determination of apoptotic and anti-apoptotic activities of the neurons, Bax and Bcl-2 levels were measured. Monosodium glutamate significantly increased Bax and decreased Bcl-2 immunoreaction in the perikarya of Purkinje cells (mean = 0.93 ±0.02 and 0.261 ±0.14 for Bax and Bcl-2; respectively, Figures 4 and 5). Monosodium glutamate increased the mean Bax/Bcl-2 ratio to 2.53 ±0.06 compared to 0.178 ±0.02 in controls (p = 0.002, Figure 6). Treatment with either MSCs significantly decreased Bax (mean = 0.52 ±0.003 and 0.48 ±0.004 for BM-MSCs and ASCs; respectively, p = 0.035 and 0.003 each vs. MSG, Figure 5); increased Bcl-2 optical density (mean = 0.367 ±0.01 and 0.39 ±0.15 for BM-MSCs and ASCs; respectively, p = 0.001 and 0.012 each vs. MSG, Figure 7); and decreased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (mean = 0.47 ±0.05 and 0.40 ±0.03 for BM-MSCs and ASCs; respectively, p = 0.003 and 0.001 each vs. MSG). There was no significant difference in Bax, Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, or Bcl-2 between the MSC-treated groups (p > 0.05 each, Figure 7).

Figure 5

Quantitative analysis of Bax optical density in the study groups (A). Bax immunostaining in the cerebellum of study groups (B–E). Control rat (B) showed positive brownish immunoreaction of Bax stain in the perikarya of Purkinje cells. The monosodium glutamate (MSG) group (C) showed an increase in positive brownish immunoreaction in the perikarya of Purkinje cells. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BM-MSC) group (D) and adipose tissue stem cell group (E) showed a decrease in positive brownish immunoreaction. Results are mean ± SEM and were analysed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey post-hoc test

*Significant p-value in comparison to control group, #significant p-value in comparison to MSG group and $significant p-value in comparison to BM-MSCs group.

Figure 6

Bax/Bcl-2 ratio in study groups. The monosodium glutamate (MSG) group was significantly increased compared to control group. Both stem cell groups showed significantly low Bax/Bcl-2 ratio when compared to the MSG group. Results are mean ± SEM and were analysed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey post-hoc test

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, *significant p-value in comparison to control group, #significant p-value in comparison to MSG group.

Figure 7

Quantitative analysis of BCL-2 optical density. A – BCL-2 immunostaining in the cerebellum (B–E). Control rat (B) showed positive brownish immunoreaction of BCL-2 stain in the perikarya of Purkinje cells. The monosodium glutamate (MSG) group (C) showed decrease in positive brownish immunoreaction in the perikarya of Purkinje cells. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells group (D) and adipose tissue stem cells group (E) showed increase in positive brownish immunoreaction. Mean ± SEM was analysed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey post-hoc test

*Significant p-value compared to control group, #significant p-value compared to MSG group.

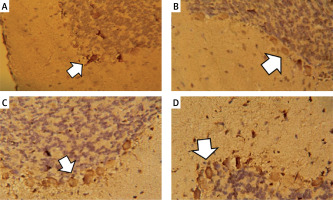

Mesenchymal stem cells enhanced cerebellar vascular endothelial growth factor and insulin-like growth factor-1 levels

Monosodium glutamate significantly decreased the cerebellar brownish VEGF immunoreaction compared to controls (mean colour percentage areas were 34.52% ±1.52 and 24.44% ±2.14 for MSG and controls, respectively, p = 0.017). Treatment with either of the MSCs significantly increased VEGF immunoreaction (mean colour percentage areas were 38.70% ±0.99 and 46.65% ±1.22 for BM-MSCs and ASCs, respectively, p = 0.013 and 0.001 each vs. MSG, Figure 8). Adipose tissue stem cells were superior to BM-MSCs at increasing VEGF (p = 0.004, Table II).

Figure 8

Vascular endothelial growth factor immunostaining in the cerebellar cortex. A – Control group. B – Monosodium glutamate group. C – Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell group. D – Adipose tissue stem cell group

Table II

Levels of cerebellar vascular endothelial growth factor and insulin-like growth factor-1 among study groups

| Parameter | Control group | MSG group | BM-MSCs group | ASCs group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | 34.52 ±1.5% | 24.44 ±2.14%*$ | 38.70 ±0.99%# | 46.65 ±1.22%*#$ |

| IGF-1 | 3.54 ±0.4 ng/ml | 5.93 ±0.35 ng/ml | 19.32 ±0.39 ng/ml*# | 39.77 ±2.34 ng/ml*#$ |

Monosodium glutamate had no significant effect on IGF-1 levels using ELISA (mean (ng/ml) = 5.93 ±0.35 and 3.54 ±0.4 for MSG vs. control, respectively, p > 0.05). Treatment with either of the MSCs significantly increased IGF-1 levels (mean (ng/ml) = 19.32 ±0.39 and 39.77 ±2.34 for BM-MSCs and ASCs, respectively, p = 0.017 and 0.002 each vs. MSG). Adipose tissue stem cells were superior to BM-MSCs at increasing IGF-1 (p = 0.013, Table II).

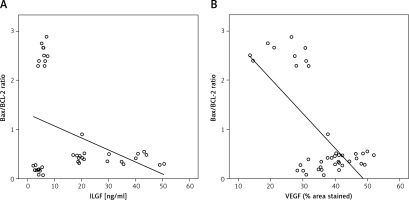

The Bax/Bcl-2 ratio negatively correlated with cerebellar insulin-like growth factor-1 or vascular endothelial growth factor levels

There was a significant negative correlation between the Bax/ Bcl-2 ratio in Purkinje cells and cerebellar IGF-1 or VEGF level (r2 = –0.374, –0.683 for IGF-1 and VEGF, respectively, Figures 9 A and B).

Sex-determining region Y gene detection

The PCR product failed to detect the SRY gene in the cerebellum of treated female rats, confirming that they were true females with XX chromosomes. Polymerase chain reaction detected the SRY gene in the DNA of male rat cerebellum at 104 bp, demonstrating the specificity of the assay (results not shown).

Discussion

This study shows for the first time the potential therapeutic role of ASCs in CA. Treatment with either of the MSCs improved MSG-induced poor motor performance, restored the disrupted Purkinje cell layer, decreased neuronal apoptosis, and enhanced VEGF and IGF-1 levels in the cerebellar cortex of a rodent model of MSG-induced CA. Adipose tissue stem cells showed superiority over BM-MSCs in the improvement of some motor performance parameters and cerebellar VEGF and IGF-1 levels.

In this study, we established a rodent model of CA using MSG. Monosodium glutamate is known to alter neurobehavioral activity by damaging neuronal cells and disrupting cerebellar function [24]. Animals treated with MSG exhibited marked deterioration in motor functions compared to controls. We observed a significant decrease in latencies on the rotarod test during all sessions of assessment, consistent with other reports [15, 23], and significant deterioration in all parameters measured throughout the 4 weeks of assessment in the open field test. These results are consistent with that of Onaolapo et al., who found that MSG reduced locomotor and rearing activities [25]. We also observed a significant reduction in both stride lengths and wide-based gait, characteristic of CA. These results are consistent with [26, 27] who analysed gaits in other animal models of CA. This wide-based gait is similar to that observed in CA patients [28] and is caused by the incoordination between the relative movements of leg joints during locomotion [29] and the increase of the support base area to compensate for the sway [27].

Establishment of CA was shown by the widely distorted and shrunken cerebellar Purkinje cell layer with significant decrease in violet Nissl’s granules within the Perikarya of Purkinje cells, as previously described [24, 30,31]. This neurodegeneration was assessed by Cresyl violet stain; a stain for Nissl’s granules in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. The observed decrease in violet Nissl granules is a sign of neurodegeneration. Monosodium glutamate-induced CA causes neurodegeneration by decreasing the intracellular protein synthesis rate [32]. In the early stages of neural degeneration, ribosomes are dissociated from the rough endoplasmic reticulum [33] causing the degenerating neurons to be poorly stained, as observed in this animal model.

Degeneration and apoptosis of Purkinjie cells is triggered by the excessive stimulation of glutamatergic receptors by glutamate (the main component of MSG) [34]. Indeed, it is the presence of 2 types of glutamatergic receptors in Purkinje cells that explains their susceptibility to MSG toxicity [35]. In this study, MSG significantly increased the pro-apoptotic Bax optical density together with a significant decrease in anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 in the perikarya of Purkinje cells, as previously reported [36, 37]. This was expected because it is known that, in response to a stressful stimuli (e.g. MSG), Bax undergoes conformational changes assembling pore-forming proteins in the mitochondrial outer membrane, inducing the release of cytochrome C, which in turns causes the activation of caspase-3 and ultimately induces cell apoptosis [38]. On the other hand, Bcl-2 prevents apoptosis by blocking the release of cytochrome C from mitochondria to the cytosol [39].

Treatment with either of the MSCs markedly improved MSG-induced defective motor functions, as shown by the gradual improvement in rotarod test, open field test, and gait, as previously reported [40, 41] This improvement was observed as early as a few days after transplantation. In fact, the ASC group showed earlier improvement of motor functions compared to the BM-MSC group in the rotarod test (second week vs. third week), mobility duration (first week vs. fourth week), fore- and hind-limb stride length (third week vs. third and fourth week), and stance width (second week vs. third week), but both treatments showed similar commencement of improvement in the open field test. Such differences in the start time of improvement might be due to the fact that open field test assesses locomotion [30], whereas both rotarod test and gait analysis assess fore- and hind-limb motor coordination and balance [42] – complex functions that would take a longer time to improve. These findings are consistent with others [43] with slight variation in the literature [40, 44,45], which could be explained by the difference in the animal model used and the type, dose, and method of administration of MSCs.

In the current study, both MSC-treated groups showed decreased numbers of degenerated Purkinje cells and significant increases in Nissl granules compared to the saline-treated group. This is consistent with other reports using BM-MSCs for the treatment of spinal cord injury and cerebellar degeneration [4, 44] or using ASCs for the treatment of ischaemic spinal cord damage [46].

Both MSC-treated groups had significantly high levels of cerebellar IGF-1 and VEGF compared to the saline-treated group. These findings are consistent with others who demonstrated that BM-MSCs secrete IGF-1 and VEGF, which were related with higher levels of neuronal survival in vitro [47]. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells were also shown to secrete a panel of various growth factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and IGF-1 in animal models of Parkinson’s disease and spinal cord injury [48, 49]. These products could explain the improvement of both of neuronal survival after lesion and animal behaviour upon BM-MSCs transplantation. On the other hand, ASCs were shown to secrete various neurotrophic factors, such as IGF-1 in vivo [50] or VEGF and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in vitro [51–53], suggesting that MSCs may release trophic factors without direct cell contact that influence regeneration, turnover, and improve functional tissue outcome.

Our study showed significant reduction of cerebellar VEGF in response to MSG, as previously reported in the normal adult brain [54]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies investigating the effect of MSG on cerebellar VEGF expression. However, MSG significantly reduced endometrial VEGF expression in a rodent model of endometrial toxicity [22].

Both MSC-treated groups showed significant decreases in Bax/Bcl-2 ratio in comparison to the saline-treated group, consistent with others [55–57]. The role of BM-MSCs in the expression of Bax and Bcl-2 remains controversial [58–60]. This controversy may be related to the differences in the animal model used in each study and subsequently the differences in its neurodegenerative microenvironment [59].

Insulin-like growth factor-1 negatively correlated with the Bax/ Bcl-2 ratio, indicating its role in lowering apoptosis. This was expected because IGF-1 possesses a potent neurotrophic effect protecting neural cells against apoptosis [42, 61]. Therefore, it is possible for IGF-1 to attenuate the MSG-induced cerebellar atrophy and cellular apoptosis in MSC-treated groups through down-regulation of Bax and up-regulation of Bcl-2 levels modulating the Bax/BCL-2 ratio, exerting an overall inhibitory effect on apoptotic cell death.

Vascular endothelial growth factor significantly correlated with Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, consistent with others [62, 63]. Growing evidence indicates that VEGF has a direct stimulant effect on neuritic outgrowth (neurotrophic) [64] and neuronal survival (neuroprotective) [65, 66] of various neuronal cell types. Tolosa et al. 2008 and Sanchez et al. 2010 explained the possible mechanism of VEGF-induced neuroprotection and attributed this to the restoration of Bcl-2 levels [62, 63]. Thus, VEGF possibly induced the modification of the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and attenuated cellular apoptosis in MSC-treated groups. Overall, our results show that IGF-1 and VEGF could be key mediators that enhanced endogenous repair by stimulating local progenitor stem cells to divide and differentiate into functional cells, and by enhancing the anti-apoptotic system in CA.

Our study showed evidence for the superiority of ASCs over BM-MSCs in the treatment of CA. This might be attributed to the significantly higher cerebellar levels of IGF-1 and VEGF in ASCs, which gave a better effect on Bax level and enhanced Purkinje cell regeneration. These effects were reflected in the motor functions, which were improved earlier in ASCs, as well as the significant difference in locomotor activity between both groups.

We did not detect MSCs in the cerebellum of either of the MSC-treated groups. Homing of stem cells in Crigler-Najjar syndrome following transplantation remains controversial [10, 15,16, 67]. This controversy may be attributed to the difference in dose and frequency of transplanted MSCs. Intravenous infusion is a minimally invasive method for MSC delivery, which relies on its ability to migrate and translocate directly through the blood-brain barrier into the damaged area in the brain [68, 69]. Several studies showed that MSCs failed to cross the blood-brain barrier and were trapped in the lungs, liver, spleen, and other organs following systemic administration [70, 71]. The blood-brain barrier thus stands as a potentially major obstacle to stem cell therapy [72, 73], which may explain our current findings. Therefore, it might not be necessary for stem cells to migrate and engraft into the lesion site to achieve improvement [74], but rather to depend on its paracrine effects as a primary mechanism of action [75], and secrete several growth factors that would improve the endogenous repair mechanisms normally activated at the lesion site [76].

In conclusion, this study shows for the first time the superiority of ASCs over BM-MSCs in the treatment of CA. MSCs restored motor functions and cerebellar structure in a CA rodent model; an effect exerted through enhancement of the secretion and/or expression of neuroprotective growth factors regulating apoptosis.