Introduction

Flaxseed (Linum usitatissiumum) is one of the most consistent sources in bioactive compounds such as polyunsaturated fatty acid, fibres, proteins, antioxidants, and lignans [1]. The translation of the Latin origin of the name, meaning “very useful”, is suggestive, considering the various products with biological effects that contain flaxseed and its fractions: flaxseed oil, whole seed, flaxseed meal, flaxseed mucilage and/or alcohol extracts, flaxseed hulls, ground whole seed, and flaxseed oleosomes [2]. Two major varieties of flaxseed products are available, but with different biological activity [1, 3]. Flaxseed contains one-third soluble and two-thirds insoluble fibres from a total of 35–45% of fibres. It also contains a high amount of α-linolenic acid, an essential fatty acid that cannot be synthesised by the human body [4]. Other biologically important compounds found in flaxseed products are linoleic acid, linolenic acid, alkaloids, cyclic peptides, lignans, polysaccharides, cyanogenic glycosides, and cadmium [2]. These compounds have remarkable antioxidant, hypotensive, anti-inflammatory, and hypoglycaemic activities [5, 6], being used for prevention of rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular (CV) diseases, and asthma [7–10].

A number of factors such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF), pro-inflammatory cytokines, and interleukins (IL) are responsible for increased levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), an important marker of systemic inflammation [11]. C-recative protein is also considered as a strong predictor of CV risk in comparison to several other inflammatory markers [12, 13]. Some studies suggest that this acute-phase protein marker, synthesised by the adipose tissue or by the liver, might be significantly influenced by the administration or consumption of different formulations of flaxseed, like flaxseed oil, flaxseed lignan, or flaxseed supplementation [14]. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to review available randomised clinical trials (RCTs) involving the use of different forms of flaxseed to evaluate their effectiveness on the CRP plasma concentration.

Material and methods

Search strategy

This study was designed according to the guidelines of the 2009 preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [15]. EMBASE, ProQuest, CINAHL, and PUBMED databases were searched using the following search terms in titles and abstracts: (“linseed” OR “flax seed” OR “flaxseed” OR “linseed meal” OR “linum usitatissimum”) AND (“c reactive protein” OR “c reaction protein” OR “c-reactive protein” OR CRP OR “protein c reactive” OR “serum c reactive protein”). The wild-card term ‘‘*’’ was used to increase the sensitivity of the search strategy. The search was limited to studies in humans published in English. The literature was searched until 1st February 2016. Two reviewers (SU and M-CS) evaluated each article independently, carried out data extraction and quality assessment. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third party (MB).

Study selection

Original studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) clinical trials with a case-control or cross-over design, (ii) investigation of the effect of flaxseed preparations on plasma CRP concentrations, (iii) providing baseline and end-trial plasma CRP concentrations in both flaxseed and control groups, and (iv) having a supplementation with flaxseed for at least 2 weeks.

Non-clinical studies, uncontrolled trials, and trials with insufficient data on CRP values in flaxseed and control groups were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Eligible studies were reviewed, and the following data were abstracted: 1) first author’s name; 2) year of publication; 3) country were the study was performed; 4) study design; 5) number of participants in the flaxseed and control groups; 6) intervention assigned to the control group; 7) type (lignan extract, ground powder, or oil) and dose of flaxseed supplement; 8) treatment duration; 9) age, gender, and body mass index (BMI) of study participants; 10) systolic and diastolic blood pressures; and 11) data regarding baseline and follow-up concentrations of CRP. Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers; disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Quality assessment

Assessment of risk of bias in the studies included in the analysis was performed systematically using the Cochrane quality assessment tool for RCTs [16]. The Cochrane tool has seven criteria for quality assessment: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation sequence concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), and other potential sources of bias. The risk of bias in each study was judged to be low, high, or unclear. Risk-of-bias assessment was performed independently by two reviewers; disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Quantitative data synthesis

Meta-analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) V2 software (Biostat, NJ) [17]. Net changes in measurements (change scores) were calculated as follows: measure at end of follow-up − measure at baseline. For single-arm, cross-over trials, the net change in plasma concentrations of CRP were calculated by subtracting the value after control intervention from that reported after treatment. All values were collated as mg/l. Standard deviations (SDs) of the mean difference were calculated using the following formula: SD = square root [(SDpre-treatment)2 + (SDpost-treatment)2 – (2 R × SDpre-treatment × SDpost-treatment)], assuming a correlation coefficient (R) equal to 0.5. If the outcome measures were reported in median and range (or 95% confidence interval (CI)), mean and standard SD values were estimated using the method described by Wan et al. [18] Where standard error of the mean (SEM) only was reported, the standard deviation (SD) was estimated using the following formula: SD = SEM × sqrt (n), where n is the number of subjects.

Net changes in measurements (change scores) were calculated for parallel and cross-over trials, as follows: (measure at the end of follow-up in the treatment group – measure at baseline in the treatment group) – (measure at the end of follow-up in the control group – measure at baseline in the control group). A random-effects model (using DerSimonian-Laird method) and the generic inverse variance method were used to compensate for the heterogeneity of studies in terms of study design, treatment duration, and the characteristics of populations being studied [19]. Inter-study heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran Q test and I2 index. In order to evaluate the influence of each study on the overall effect size, sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave-one-out method, i.e. iteratively removing one study each time and repeating the analysis.

Meta-regression

A weighted random-effects meta-regression using an unrestricted maximum likelihood model was performed to assess the association between the overall estimate of effect size with potential moderator variables, including dose and duration of supplementation with flaxseed.

Publication bias

Potential publication bias was explored using visual inspection of Begg’s funnel plot asymmetry, and Begg’s rank correlation and Egger’s weighted regression tests. The Duval and Tweedie “trim and fill” method was used to adjust the analysis for the effects of publication bias [20].

Results

Search results and trial flow

The initial screening comprised 587 full text articles, and we removed the articles with titles that were obviously irrelevant. Selected articles were hand searched to identify further relevant studies. Among 19 full text articles assessed for eligibility, two studies were excluded, being not controlled for flaxseed supplementation (Figure 1). After final assessment, 17 eligible trials achieved the inclusion criteria and were preferred for the final meta-analysis [7, 21–36].

Characteristics of included studies

In total, 1256 individuals were included to the meta-analysis, 639 participants were allocated to the flaxseed supplementation group and 617 to the control group. The number of participants in the analysed studies ranged from nine to 85 in the flaxseed group and from eight to 94 in the control group. The included studies were published between 2007 and 2015, and were conducted in the USA (n = 5), Brazil (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), China (n = 2), Greece, Denmark, and Iran. The following flaxseed supplementation was administered in the included trials: ground powder 13 g to 60 g/day (2.9 g to 10 g ALA/day), oil containing 1.022 g to 8 g ALA/day, and derived lignan complex 360 mg to 600 mg total SDG/day. Duration of flaxseed supplementation ranged between 2 weeks and 12 months. Ten trials were designed as a parallel group and seven as crossover studies. Table I shows the demographic characteristics and baseline parameters of the included studies. No adverse events related to the supplementation were reported.

Table I

Demographic characteristics and baseline parameters of the studies selected for analysis

| Parameter | Study | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kontogianni et al. [21] | Hutchins et al. [22] | Zong et al. [23] | Barre et al. [24] | Lemos et al. [25] | Rhee et al. [26] | Faintuch et al. [27] | Pan et al. [28] | Dodin et al. [29] | Bloedon et al. [30] | Hallund et al. [31] | Kaul et al. [32] | Nelson et al. [33] | Faintuch et al. [34] | Cassani et al. [35] | Demark- Wahnefried et al. [36] | Khalatbari Soltani et al. [6] | |

| Year | 2013 | 2013 | 2013 | 2012 | 2012 | 2011 | 2011 | 2009 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008 | 2007 | 2007 | 2015 | 2008 | 2013 |

| Location | Greece | USA | China | Canada | Brazil | USA | Brazil | China | Canada | USA | Denmark | Canada | USA | Brazil | Brazil | USA | Iran |

| Design | Randomized, placebo-controlled crossover group trial | Randomized, placebo-controlled crossover group trial | Randomized single-blind placebo-controlled parallel group trial | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover group trial | Randomized double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled parallel group trial | Randomized placebo-controlled crossover group trial | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled parallel- group trial | Randomized double-blind crossover group trial | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled parallel group trial | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled parallel group trial | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover group trial | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled parallel- group trial | Randomized controlled parallel- group trial | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover group trial | Randomized single blind controlled parallel- group trial | Randomized, multicentre, controlled parallel group trial | Randomized, unblinded, controlled parallel group trial |

| Duration of trial | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 12 weeks | 3 months | 4 months | 12 weeks | 12 weeks | 12 weeks | 12 months | 10 weeks | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 8 weeks | 2 weeks | 42 days | 30 days | 8 weeks |

| Inclusion criteria | Healthy, normal weight males and females aged 18–35 years | Overweight or obese men and postmenopausal women with pre- diabetes (impaired fasting glucose between 100 and 125 mg/dl) | Individuals screened for metabolic syndrome following low-intensive lifestyle counselling | Patients 55 years of age or older, being postmenopausal (no menstruation for at least one year), not on insulin or changing exercise patterns, and healthy aside from type 2 diabetes | Patients with terminal renal failure who were undergoing chronic haemodialysis | Obese glucose intolerant people | Active males or females 18–65 years-old with BMI > 40 kg/m2, or > 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities, plus hsCRP > 5 mg/l | Type 2 diabetic patients 50–79 years of age (women postmenopausal for at least 1-year); LDL-C level > 2.9 mmol/l, and not using exogenous insulin for glycaemic control | Women with at least 6 months of amenorrhea in the year before entry into the study and a normal mammogram in the past 2 years | Men and post-menopausal women between the ages of 44 and 75 with hypercholesterolemia | Healthy postmenopausal women (defined as no menstrual period for > 24 month) | Healthy male and female volunteers | Healthy adult males and females abdominally overweight/obese (WC > 81 cm for females; WC > 94 cm for males) aged 20–68 years | Males and females, 18–65 years old, BMI > 40 kg/m2 (or > 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities), non-hospitalized and receiving oral diet, with elevated C-reactive protein > 5 mg/l | Males with at least three of the following cardiovascular risk factors: WC ≥ 90 cm; BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2; fasting TC ≥ 200 mg/dl, LDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dl, HDL-C < 40 mg/dl, TG ≥ 150 mg/dl; glycemia ≥ 100 mg/dl; SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg | Patients with biopsy-confirmed prostatic carcinoma electing prostatectomy as their primary treatment and at least 21 days from scheduled surgery | Adult haemodialysis patients with dyslipidaemia (TG > 200 mg/dl and/or HDL-C < 40 mg/dl) aged between 23 and 77 years |

| Flaxseed form | Flaxseed oil | Ground flaxseed powder | Ground flaxseed powder | Flaxseed lignan complex | Flaxseed oil | Ground flaxseed powder | Ground flaxseed powder | Flaxseed lignan complex | Ground flaxseed powder | Ground flaxseed powder | Flaxseed lignan complex | Flaxseed oil | Flaxseed oil | Ground flaxseed powder | Ground flaxseed powder | Ground flaxseed powder | Ground flaxseed powder |

| Flaxseed intervention | 15 ml/day containing 8 g of ALA | 13 g ground flaxseed containing 2.9 g of ALA | 30 g ground whole flaxseed providing 7 g ALA | 4 capsules – 600 mg total SDG/day | 2 g/day (2 capsules) | 40 g/day | 60 g/day containing 10 g ALA/day | 3 capsules – 360 mg total SDG/day | 40 g/day** | 40 g/day | 500 mg total SDG/day | 2 g/day (2 capsules) containing 1022 mg of ALA/day | ~11.6 g ALA/day | 30 g/day ~5 g of ALA | 60 g/day | 30 g/day | 40 g/day |

| 26 g ground flaxseed containing 5.8 g of ALA | 30 g /day + low-fat diet | ||||||||||||||||

| Participants: | |||||||||||||||||

| Case | 37 | 25 | 83 | 16 | 70 | 9 | 10 | 70 | 85 | 30 | 22 | 22 | 27 | 24 | 14 | 40 | 15 |

| 40 | |||||||||||||||||

| Control | 90 | 75 | 8 | 94 | 32 | 22 | 24 | 13 | 41 | 15 | |||||||

| Age [years]: | |||||||||||||||||

| Case | 25.6 ±5.9 | 58.6 ±6.3 | 48.9 ±8.1 | 66.2 ±1.7* | 55.7 ±13.0 | 54.7 ±6.6 | 47.8 ±8.0* | 62.9 ±7.5 | 54.0 ±4.0 | 56.8 ±7.3 | 61 ±7 | 34.70 ±1.69* | 37.74 ±11.8 | 40.8 ±11.6 | 40 ±9 | 60.2 ±7.0 | 54.0 ±4.0* |

| 59.3 ±7.6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Control | 48.7 ±7.9 | 58.3 ±14.8 | 50.7 ±6.4* | 55.4 ±4.5 | 57.0 ±8.0 | 32.93 ±1.99* | 39.42 ±10.45 | 33 ±10 | 58.2 ±6.8 | 54.5 ±4.0* | |||||||

| Male (%): | |||||||||||||||||

| Case | 21.62 | 44.0 | 56.6 | NS | 55.7 | 44.4 | NS | 37.14 | 0.0 | 53.33 | 0.0 | NS | 21.0 | 17.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 66.6 |

| 100.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Control | 55.6 | 61.3 | NS | 0.0 | 46.87 | NS | 22.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 40.0 | |||||||

| BMI [kg/m2]: | |||||||||||||||||

| Case | 21.9 ±2.5 | 30.4 ±5.3 | 25.1 ±2.3 | 31.2 ±2.2* | 25.1 ±3.47 | 32.4 ±8.2 | 44.0 ±3.9* | 24.2 ±0.7 | 25.5 ±4.5 | 27.4 ±4.4 | 24.1 ±3.4 | 28.32 ±0.46* | 29.31 ±4.27 | 47.1 ±7.2 | 32 ±3 | 28.5 ±3.9 | 25.5 ±2.0* |

| 28.5 ±4.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Control | 22.0 ±2.6 | 25.5 ±2.4 | 24.2 ±4.27 | 32.0 ±8.3 | 45.2 ±4.2* | 24.4 ±0.7 | 26.8 ±4.6 | 28.1 ±5.1 | 28.77 ±0.78* | 30.23 ±4.14 | 47.2 ±7.2 | 32.1 ±2.8 | 28.8 ±4.0 | 27.0 ±1.0* | |||

| hs-CRP [mg/l]: | |||||||||||||||||

| Case | 0.45 ±0.47 | 3.0 ±3.2 | 1.01 (0.72–2.12) | 2.4 ±1.1* | 8.0 (2.3–16.8) | 3.6 ±1.7 | 12.9 ±7.2* | 1.67 ±0.19* | 2.02 ±2.60 | 1.36 (0.85–2.7)# | 0.88 (0.63–2.05)# | 319 ±65* | 2.40 ±2.39 | 13.7 ±9.9 | 2.04 ±1.48 | 1.4 (1.0–2.7)## | 4.8 ±0.9* |

| 3.2 ±2.8 | 1.2 (0.9–2.5)## | ||||||||||||||||

| Control | 0.66 ±1.06 | 2.9 ±3.0 | 1.12 (0.75–1.97) | 2.7 ±1.2* | 4.4 (2.3–7.6) | 3.6 ±1.7 | 10.5 ±5.5* | 1.42 ±0.19* | 2.18 ±2.29 | 1.06 (0.37–1.7)# | 0.80 (0.62–1.62)# | 314 ±69* | 2.79 ±1.80 | 11.8 ±8.2 | 2.76 ±2.45 | 1.5 (1.1–2.2)## | 4.0 ±0.6* |

| SBP [mm Hg]: | |||||||||||||||||

| Case | NS | NS | 134.4 ±17.0 | 133.6 ±4.8* | NS | NS | 126 ±10* | 124 ±3 | 125.4 ±14.5 | NS | 124 ±13 | NS | NS | NS | 139 ±20.3 | NS | NS |

| NS | NS | ||||||||||||||||

| Control | NS | NS | 134.5 ±14.5 | 135.8 ±4.3* | NS | NS | 138 ±25* | 123 ±3 | 122.4 ±15.5 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 134 ±9.2 | NS | NS | |

| DBP [mm Hg]: | |||||||||||||||||

| Case | NS | NS | 86.3 ±11.3 | 82.1 ±1.9* | NS | NS | 79 ±3* | 79.2 ±10.7 | 79.7 ±9.4 | NS | 75 ±8 | NS | NS | NS | 83 ±13.5 | NS | NS |

| NS | NS | ||||||||||||||||

| Control | NS | NS | 85.9 ±8.8 | 84.5 ±2.2* | NS | NS | 92 ±16* | 79.3 ±10.3 | 77.7 ±9.4 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 80 ±7.7 | NS | NS | |

** half of the daily amount was given as two slices of bread, which replaced the usual bread in the diet, and the other 20 g was provided as ground grains to add to cereal, juice, or yogurt, depending of the food preferences of the women

BMI – body mass index, NS – not stated, SBP – systolic blood pressure, DBP – diastolic blood pressure, hs-CRP – high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, BMI – body mass index, CHD – coronary heart disease, ALA – α-linolenic acid, SDG – secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, WC – waist circumference, LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG – triglycerides.

Risk of bias assessment

An unclear risk of bias with respect to sequence generation and allocation concealment was observed. Some trials were not blinded, but studies were low risk in terms of other sources of bias. The systematic assessment of bias in the included studies is shown in Table II.

Table II

Assessment of risk of bias in the included studies using Cochrane criteria

| Study | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other potential threats to validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kontogianni et al. 2013 [21] | U | U | H | L | L | L | L |

| Hutchins et al. 2013 [22] | U | U | H | L | L | L | L |

| Zong et al. 2013 [23] | U | U | H | L | L | L | L |

| Barre et al. 2012 [24] | U | U | L | L | L | L | L |

| Lemos et al. 2012 [25] | U | U | L | L | L | L | L |

| Rhee et al. 2011 [26] | U | U | H | L | L | L | L |

| Faintuch et al. 2011 [27] | U | U | L | L | L | L | L |

| Pan et al. 2009 [28] | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Dodin et al. 2008 [29] | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Bloedon et al. 2008 [30] | U | U | L | L | L | L | L |

| Hallund et al. 2008 [31] | U | U | L | L | L | L | L |

| Kaul et al. 2008 [32] | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Nelson et al. 2007 [33] | U | U | H | H | L | L | L |

| Faintuch et al. 2007 [34] | U | U | L | L | L | L | L |

| Cassani et al. 2015 [35] | U | U | U | U | L | L | L |

| Demark-Wahnefried et al. 2008 [36] | L | L | H | L | L | L | L |

| Khalatbari Soltani et al. 2013 [6] | U | U | H | U | L | L | L |

Effect of flaxseed supplementation on plasma CRP concentrations

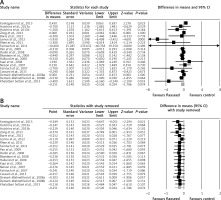

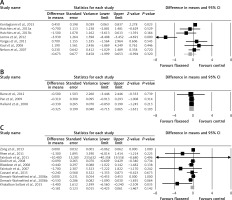

Meta-analysis of data from 17 trials did not suggest a significant change in plasma CRP concentrations following supplementation with flaxseed-containing products (WMD: –0.25 mg/l, 95% CI: –0.53, 0.02, p = 0.074; Q = 46.33, I 2 = 61.15%) (Figure 2 A). The effect size was robust in the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (Figure 2 B). Subgroup analysis did not suggest any significant difference in terms of changing plasma CRP concentrations among different types of flaxseed supplements used in the included studies, i.e. flaxseed oil (WMD: –0.67 mg/l, 95% CI: –2.00, 0.65, p = 0.32; Q = 28.63, I 2 = 82.54%) (Figure 3 A), lignan extract (WMD: –0.32 mg/l, 95% CI: –0.71, 0.06, p = 0.103; Q = 0.02, I 2 = 0%) (Figure 3 B), and ground powder (WMD: –0.18 mg/l, 95% CI: –0.42, 0.06, p = 0.142; Q = 13.44, I 2 = 33.06%) (Figure 3 C).

Meta-regression

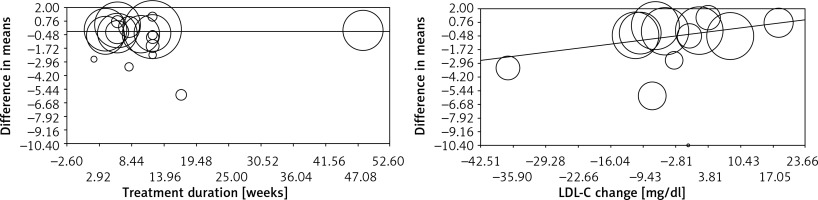

Meta-regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between changes in plasma CRP concentrations and potential confounders, including duration of supplementation with flaxseed and changes in plasma LDL-C concentrations. No significant association was found between changes in plasma CRP levels with either supplementation duration (slope: –0.001; 95% CI: –0.02 to 0.02; p = 0.928) or plasma LDL-C changes (slope: 0.05; 95% CI: –0.01 to 0.12; p = 0.095) (Figure 4).

Publication bias

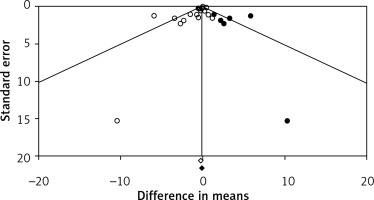

Visual inspection of funnel plots suggested an asymmetry in the meta-analyses of flaxseed’s effects on plasma CRP concentrations. Using a “trim and fill” method six potentially missing studies were imputed on the right side of the funnel plot (Figure 5). However, the corrected effect size remained non-significant after imputation (WMD: –0.10 mg/l, 95% CI: –0.42, 0.22). The results of Egger’s linear regression (intercept = –0.86, standard error = 0.35; 95% CI: –1.59, –0.12, t = 2.44, df = 18, two-tailed p = 0.025) but not Begg’s rank correlation (Kendall’s τ with continuity correction = –0.19, z = 1.20, two-tailed p = 0.223) suggested publication bias in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

This meta-analysis did not suggest a significant change in plasma CRP concentrations following supplementation with flaxseed-containing products. Subgroup analysis also did not suggest any significant difference in terms of changing plasma CRP concentrations among different types of flaxseed supplements used in the included studies, i.e. flaxseed oil, lignan extract, and ground powder.

A reason for these effects could be that flaxseed oil does not contain eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) fatty acids, while the presence of α-linolenic acid may not be sufficient for such beneficial effects [8]. Despite the fact that α-linolenic acid undergoes conversions to longer-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids or essential fatty acids such as EPA, docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and DHA, the exact percentage of these conversions in the cells, plasma, and tissues are still not known [37]. The α-linolenic acid contained in flaxseed products was shown to inhibit the metabolisation of arachidonic acid to more inflammatory cytokines [38]. Furthermore, different factors such as smoking, gender, and high intake of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids were shown to affect the metabolic capacity of α-linolenic acid conversions [39, 40]. It has been shown that younger women have a greater capacity of conversion of α-linolenic acid to essential fatty acids than older women and men, due to having a hormonal profile more sensitive to diet [41]. This capacity of conversion of α-linolenic acid to essential fatty acids is even greater during the period of pregnancy and lactation.

Another fact that may account for these results is that less than 10% of dietary α-linolenic acid is incorporated in the plasma phospholipid pool [42]. Moreover, the beneficial effects of α-linolenic acid derived from plant sources, which is less effective than omega-3 obtained from animal sources, might also influence the results on flaxseed supplements and products on plasma CRP levels.

Lignans, the precursors of enterodiol and enterolactone, are also important compounds found in flaxseed products converted by the microbial flora in the colon [8, 43]. The administration of the principal lignan of flaxseed, secoisolariciresinol diglucoside and its primary metabolites: secoisolariciresinol (SECO), enterodiol (ED), and enterolactone (EL), on male Wistar rats, showed short half-lives, a large volume of distribution, and a high systemic clearance [44]. These pharmacokinetics properties of lignans might also explain the lack of effects of flaxseed products on plasma CRP levels. Another potential reason may lie in the fact that the effects of fatty acids on inflammatory cells are modulated by changes in fatty acid composition of cell membranes, causing lipid raft production, changes of membrane fluidity, and modifications of gene expression and of the pattern of peptide and lipid mediator production [45–50].

The present meta-analysis has some limitations. There were only a few eligible RCTs, and most of them had a small number of participants with suitable short time of supplementation, and they were heterogeneous regarding the characteristics of patients and study design. Many characteristics that vary within studies, such as the type of flaxseed products, the background of the patients included, the control groups, or the quality of the studies, could have been factors of between-study heterogeneity. Our results showed that the significance of estimated pooled effect size was not biased by any single study.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis of available randomised controlled trials does not suggest any significant benefit of flaxseed product supplementation in decreasing plasma CRP concentrations. Larger, well-designed studies with higher doses and longer follow-up should be performed to validate the current results.